Sat, Feb 21, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 1, Issue 3 (Spring 2023)

CPR 2023, 1(3): 300-315 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Beyraghi N, Soklaridis S, Srikanthan C, Rodak T, Buckley L, Waddell A. Impact of Suicide on Fellow Patients Exposed to Suicide in Clinical Settings and Postvention Strategies: A Scoping Review. CPR 2023; 1 (3) :300-315

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-60-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-60-en.html

Narges Beyraghi

, Sophie Soklaridis

, Sophie Soklaridis

, Camellia Srikanthan

, Camellia Srikanthan

, Terri Rodak

, Terri Rodak

, Leslie Buckley

, Leslie Buckley

, Andrea Waddell

, Andrea Waddell

, Sophie Soklaridis

, Sophie Soklaridis

, Camellia Srikanthan

, Camellia Srikanthan

, Terri Rodak

, Terri Rodak

, Leslie Buckley

, Leslie Buckley

, Andrea Waddell

, Andrea Waddell

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Full-Text [PDF 2013 kb]

(584 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1684 Views)

Full-Text: (481 Views)

Introduction

In psychiatric hospitals, fellow patients are at a higher risk of being exposed to the suicide of patients [1]. When a suicide occurs in these settings, the impact on other patients can be high [2] . There is scant research on how the suicides in psychiatric settings can significantly affect the fellow patients [3, 4] Experts believe that a person who is exposed to suicide, regardless of her/his relationship with the deceased, may experience a more complicated and prolonged form of grief [5, 6]. Patient suicide affects those exposed to this event. Each suicide creates 11 victims: the person who died and the 10 caregivers, family, and friends [7]. There is a distinction between “suicide survivorship” and “exposure to suicide”. The first refers to the one who had a personal and close relationship with the deceased. The second refers to a situation where a person with no close relationship with the deceased was indirectly informed about the death or witnessed the death of a stranger [8]. Fellow patients may have different types of relationships in clinical settings that can affect the aftermath of a suicide. Patients in group therapies and peer support groups are examples of patients who may have stronger relationships with each other [6, 9]. On the other hand, acute care settings usually provide services to more vulnerable patients with mental health problems, history of suicidal thoughts or attempts, or psychosocial disorders [6]. Despite the existence of evidence about the risk of a suicide in other groups with close relationships, there is a limited information about the risk of suicide among fellow patients in a clinical setting [8].

Suicide is a traumatic event. Suicide bereavement is associated with trauma and grief. Being exposed to suicide leads to higher rates of suicidal thoughts in the bereaved, regardless of the type of relationship with the deceased [10]. Postvention is essential in these situations and can be life-saving. Postvention strategies refer to activities after a suicide for destigmatizing suicide and promoting recovery in the bereaved survivors. Current studies have primarily focused on suicide prevention and risk assessment, and not on the aftermath of suicide. The literature have indicated a high and persistent risk for adverse sequelae in the bereaved survivors even 10 years after suicide [1]. Clinical postvention strategies for fellow patients should address their recovery process to remove the stigma associated with suicide and act as secondary prevention to reduce the risks of suicide in them [11].

There is a scant research on the effects of suicide on fellow patients and the use of post-suicide interventions for these people. Gaining information about the postvention protocols can enhance the quality of care for these people. Therefore, this scoping review study aims to systematically analyze the current evidence on the postvention strategies and the aftermatch of suicide in a clinical setting on the fellow patients . The objectives of this review study are as following:

1. Surveying the experiences of fellow patients of after a suicide;

2. Investigating the interventions available to fellow patients after a suicide;

3. Providing recommendations for the support of the bereaved.

Materials and Method

This is a scoping review study using The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis: Development of a Scoping Review Protocol [12]. The research team discussed and revised the protocol based on feedback. The final protocol was prepared on November 15, 2020. The articles published from 2000 to 2020 in English, grey literature (e.g., reports, theses, unpublished research materials, newspapers, website materials, and policy papers), qualitative and quantitative studies in clinical settings (hospital or community health centers), the studies on the impact of suicide on fellow patients containing information on post-suicide interventions were included in the search. The articles not available in English, those focused only on the bereaved individuals who fellow patients (e.g., family members, health care providers), those conducted only on children and adolescents, those only about suicide prevention or suicide risk assessment, book chapters, and conference abstracts were excluded.

The search was conducted using subject headings and keywords in the following databases: Medline, Embase, APA PsycInfo, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. A medical librarian (TR) developed the search strategies and conducted searches on December 22, 2020. The keywords related to the patient suicide included «suicide», «intentional overdose», «self-inflicted» combined with terms used for psychiatric settings and patients such as «psychiatric hospitals», «community mental health services», «inpatients». The keywords related to the bereaved survivors included «therapeutic community», «group psychotherapy», and «group member», “institutional policies”, “response protocol”, and “postvention. For related grey literature, the search was conducted by Google and Google Scholar engines using the following terms: «co-patient», «other patients», «fellow patient», «inpatient», «suicide», and «postvention». The first five pages of results for each query were examined for relevant materials. The references of the found articles were also checked to ensure no relevant articles were missed. We also contacted the relevant organizations by email to inquire if additional information can be added to clarity to the search results. The following organizations were contacted: Mental Health Commission of Canada, the Royal Mental Health Care & Research, the Cochrane Consumer Network, the National Institute of Mental Health, Campbell Collaboration, and the World Health Organization (WHO). The information provided by the organizations related to suicide prevention efforts rather than postvention methods were not included in the review.

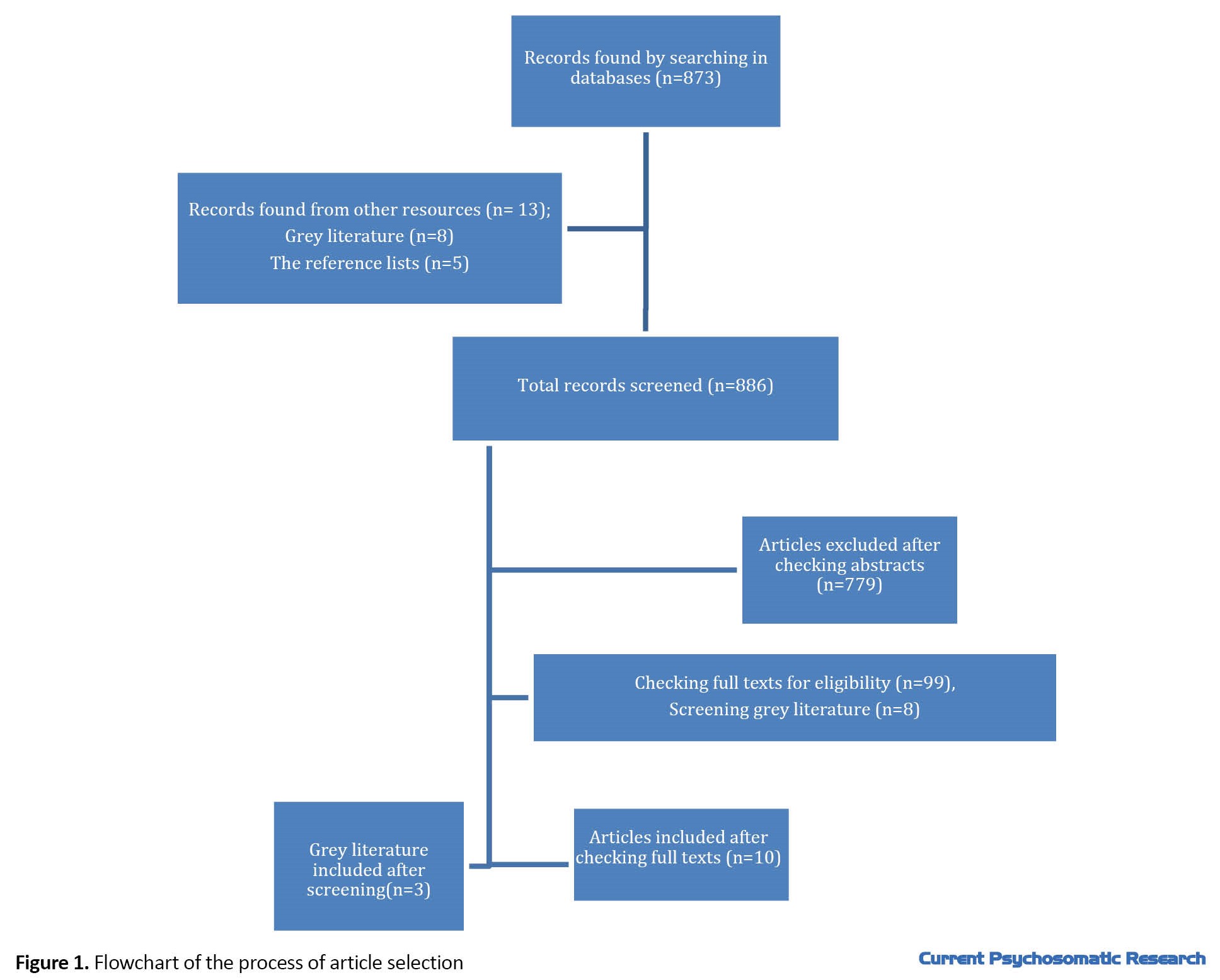

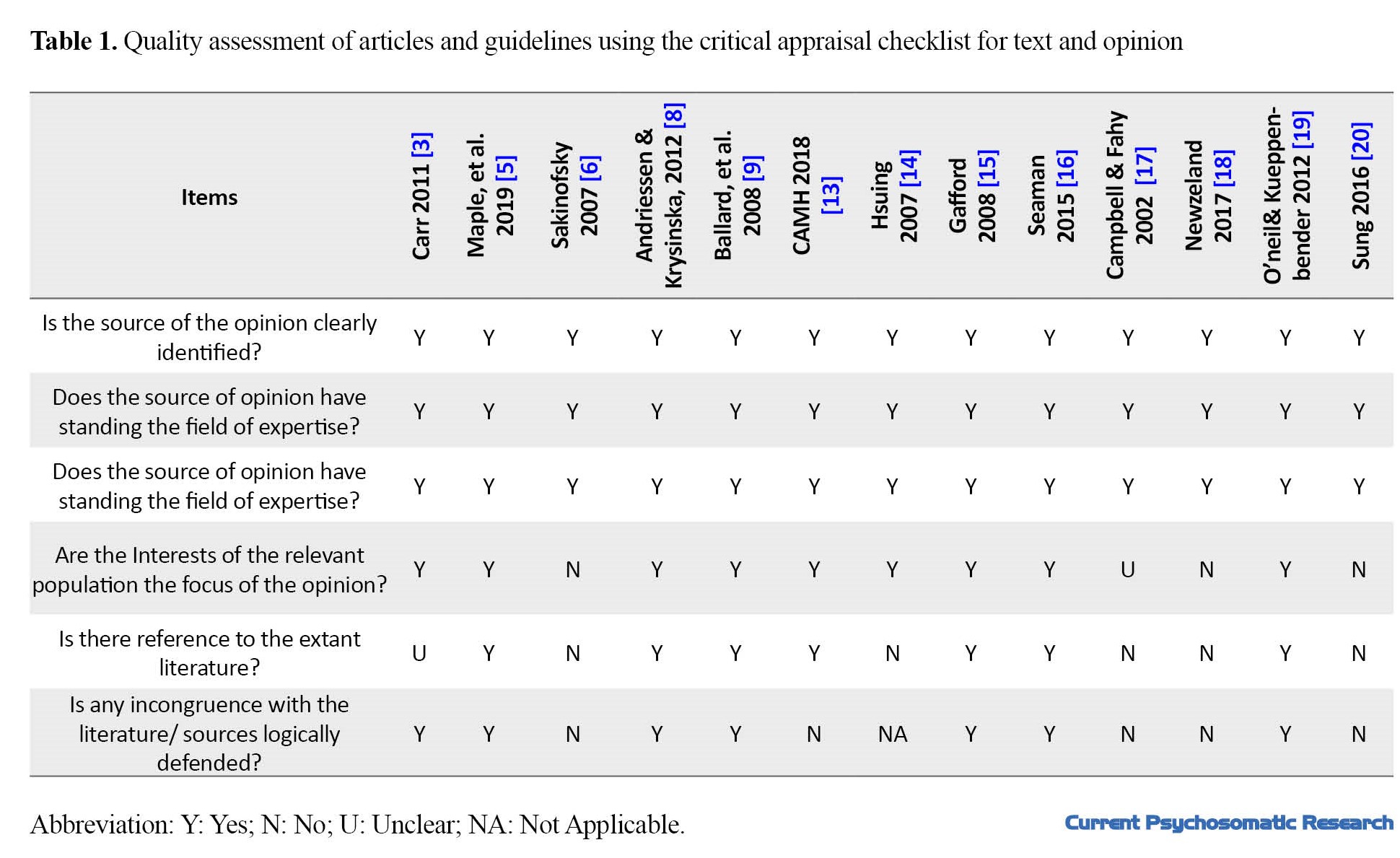

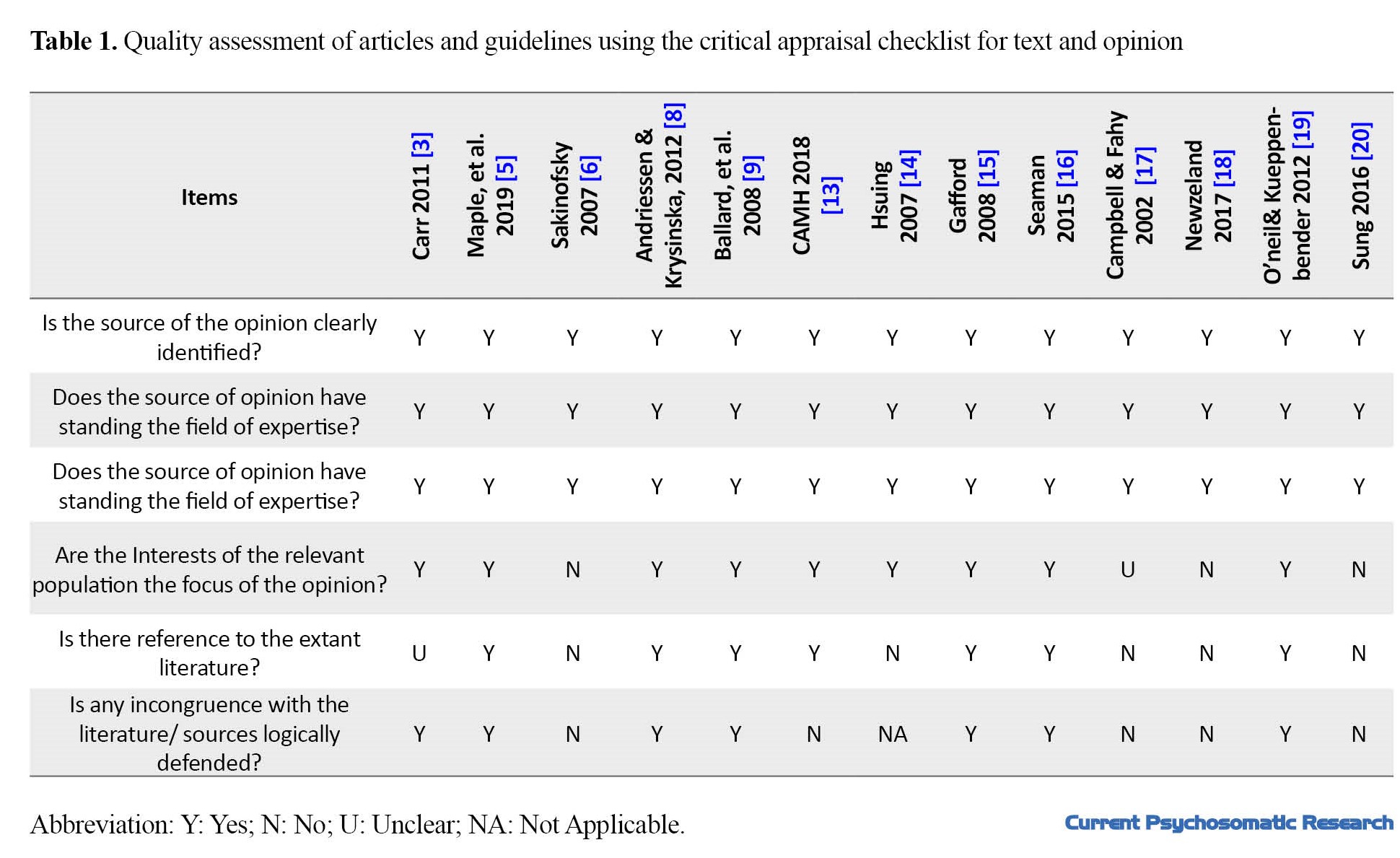

The list of the found articles was imported into the Covidence website to screen their titles, abstracts, and subsequently full-texts. The duplicate articles were removed before screening the titles and abstracts. Two authors (NB, AW) independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility and had a group discussion to resolve any conflicts identified on Covidence. Two authors (NB,CS) later screened the full texts independently and discussed the conflicts that needed to be resolved until a final decision was made on which articles should be included in the data extraction stage. Two authors (NB, CS) independently completed the data extraction from the full texts and compared the details until a consensus was reached. Figure 1 presents the summary of the screening process. JBI’s critical appraisal checklist was used for the quality assessment of studies (Table 1).

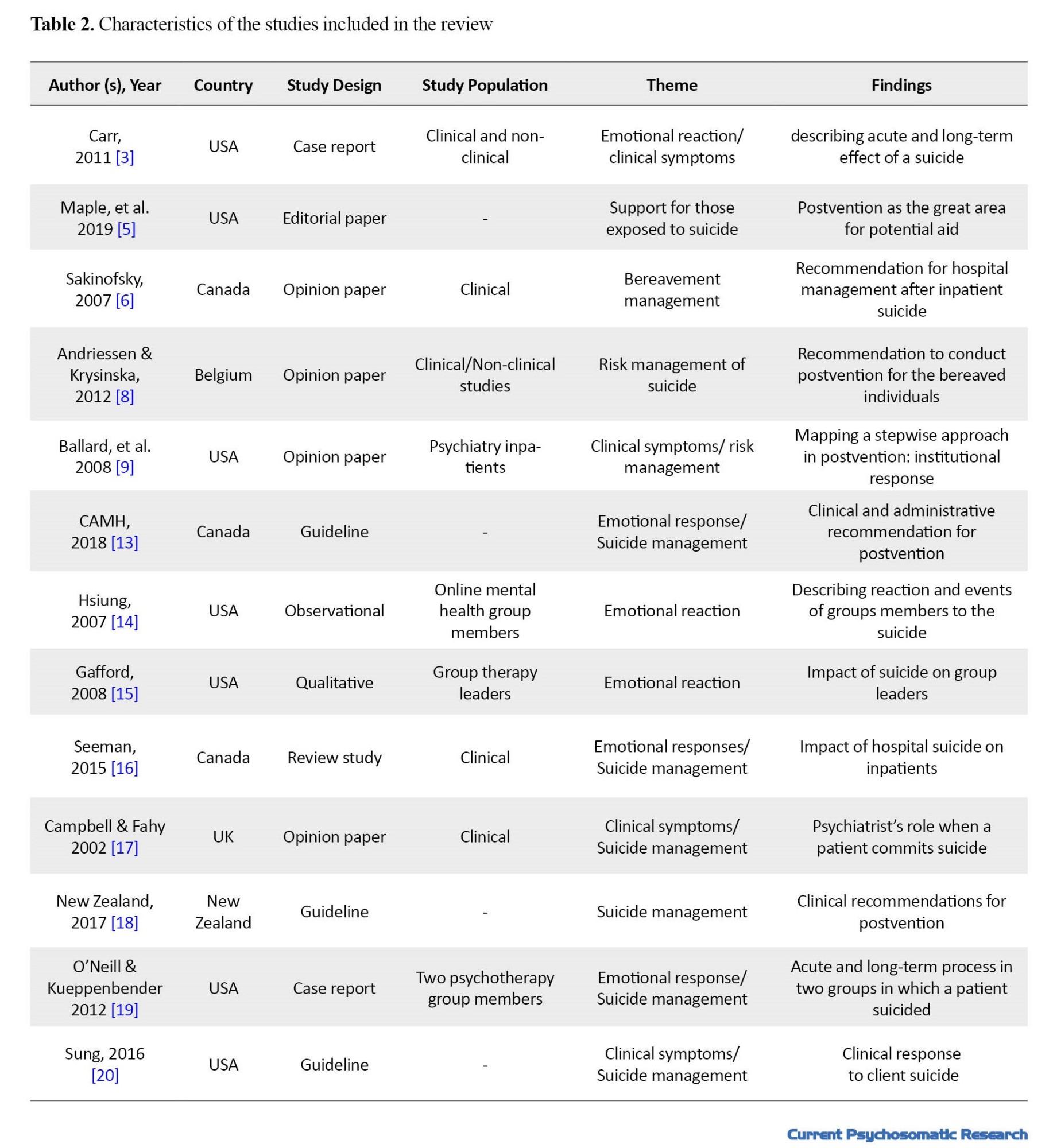

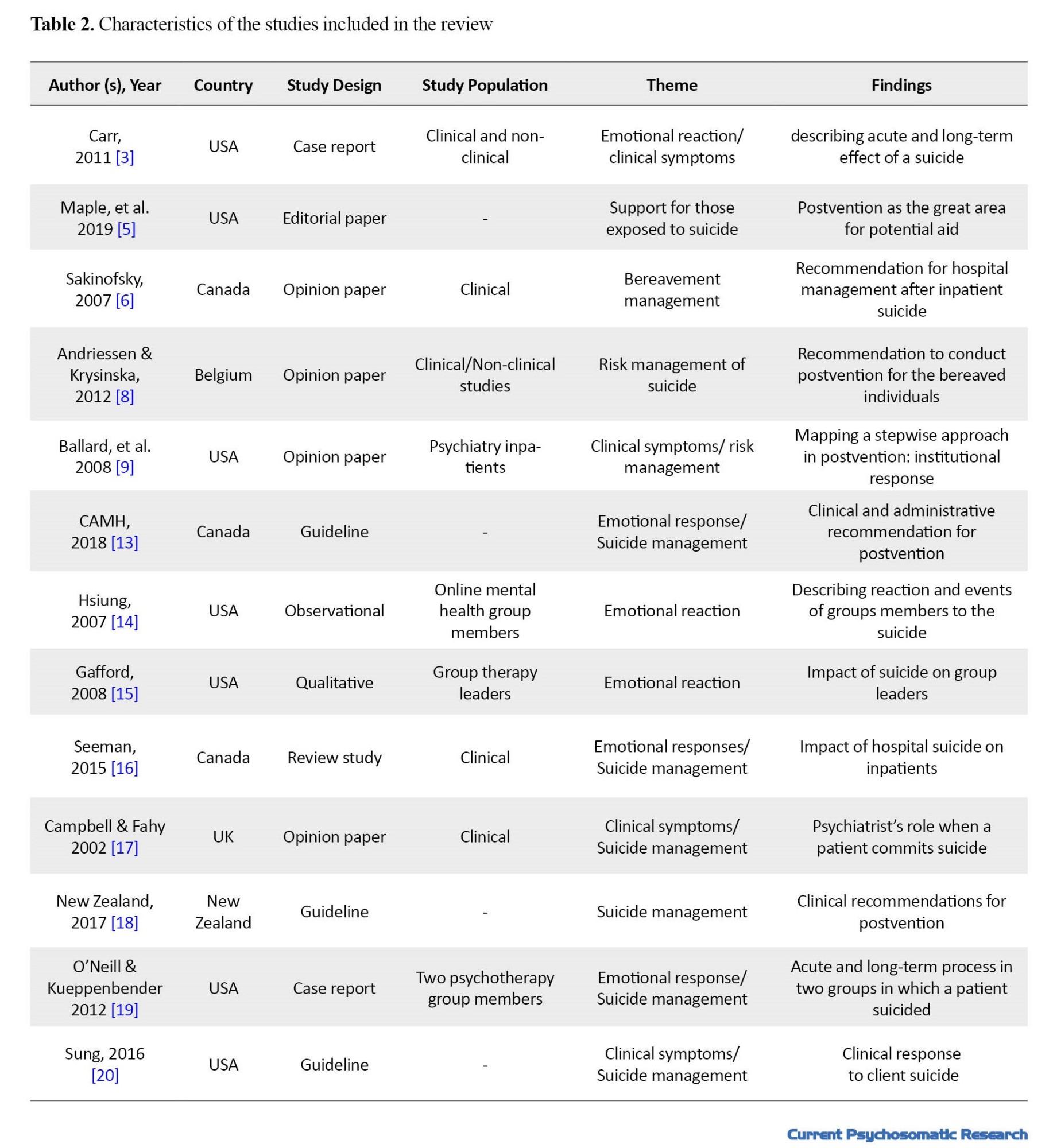

The extracted data included authors’ information (name, affiliations, country, study area), study populations, methodology, and findings. A summary of this information is provided in Table 2.

Results

Fellow patients’ experiences with suicide

Eight articles described fellow patients’ experience after a suicide event. Three sub-themes were thus identified: Emotional responses to the suicide, Clinical symptoms as the aftermath of the suicide, and suicide contagion and suicide management.

Emotional responses to the suicide

When a suicide happens in a therapeutic setting, other patients may show different emotional reactions. Three articles described fellow patients’ feelings of shock, disbelief, denial, confusion, disorientation, guilt, and sadness following a suicide [3, 13, 14]. One article provided information on fellow patients’ reactions that were more specific to suicide from a psychodynamic perspective [15]. Four articles describe fellow patients’ reactions that were more specific to the suicide event. Two articles described how fellow patients experienced feelings of abandonment and anger towards the deceased. Asking other patients with a similar experience for support was reported in group therapy settings. Identifying the suicide victim and seeing the worst outcome as inevitable were reported as early reactions [16]. Seeking for answers can lead to self-blaming and rumination about the deceased [5]. One article reported that fellow patients held the medical staff responsible for not preventing the suicide. This article suggested that anger towards health care providers may be the presentation of displaced anger at the person who committed suicide [3]. The accusation of other fellow patients and medical staff were also been reported as the aftermath of suicide [6].

Clinical symptoms

Post-suicide mental health problems result from the interaction between the events, the type of relationship with the suicide victim, and the vulnerability or resilience of the fellow patient [16, 17]. Factors that further cause clinical symptoms include poor psychosocial support, history of trauma or recent loss, psychological disorders, chronic diseases, and history of suicide attempt [6, 18]. Studies reported somatic symptoms, intrusive flashback memories, increased anxiety, tension, psychological arousal, and poor sleep quality in affected fellow patients [3, 15, 16]. Depressive symptoms may start after the suicide and become a complete depressive episode one month after the suicide, and can persist for several months [6, 15, 19]. Patients exposed to suicide experienced symptoms as an acute stress reaction such as dissociative episodes, hypervigilance, and poor sleep quality [3, 16]. In one study, a fellow patient who found the deceased reported an inability to sleep due to seeing the deceased’s face when closing his eyes [3]. Development of homicidal ideation and exacerbation of psychotic symptoms were also reported in some studies [3, 15, 16]. In one study, a fellow patient who was experiencing pathological denial accused another member of homicide [3]. Patients who are actively psychotic may have delusional thoughts about the suicide or claim responsibility, reporting some relationship with an imagined aggressor, or believe that they caused the suicide [13].

Suicide contagion and suicide management

Relationship with the deceased and the desire to emulate their actions was reported in four studies [3, 13, 14, 16].The suicidal thoughts of fellow patients may intensify their anxiety about being at risk for suicide [13]. Being emotionally close to the suicide victim and having a history of self-harm are risk factors of suicide contagion [3, 16]. Being a psychiatric patient can cause multiple exposures to suicide. Each suicide event have a cumulative impact, which can increase the possibility of adverse reaction when exposed to suicide [5]. Suicide contagion is mainly considered as a short-term response, and the pain caused by exposure in the long term may have a restraining effect [6]. Limited information exist about the fellow patients’ long-term reaction to suicide. Two articles examined long-term responses during a group therapy, reporting that the suicide thoughts decrease over time, although the event is still mentioned on its anniversary [14, 15].

Suicide postvention for fellow patients

Those exposed to suicide require immediate, short-term, and long-term supports.

Immediate support

Immediate reactions to suicide mainly include self-destructive behaviors and acute reactions. It is essential to develop a clear and structured plan for its management, while avoiding emotional and overreacting responses [3, 9]. Suicides that occur within an inpatient unit necessitate the careful monitoring of patients with active suicidal ideation. These patients can benefit from more intensive individual support services [3, 13, 18]. An experienced clinician needs to provide an accurate description of the suicide event to other inpatients [9]. This description should respect the confidentiality of the deceased, and be tailored based on the conditions of fellow patients. Withholding information from other patients is a very conservative approach for keeping the privacy rights of the deceased, and is unfeasible if the information has already spread. Debriefing is a good way to help patients and prevent the spread of rumors in the absence of accurate information [13]. It can facilitate health-related discussions and requesting support from experienced medical staff [9, 16, 20]. Before having a debriefing session with fellow patients, a staff is needed to coordinate the responses, during which the team decide if external support is needed [9, 14]. Debriefing sessions are recommended to assess each patient’s needs, in addition to providing information. One of the goals of this method is to address the patients’ anxiety and consider safety concerns, even though other discussions may emerge. The medical team needs to decide whether individual support or group support is a better to address the varying needs of patients in each unit. Different conversations may arise during the debriefing that may be difficult to manage in a group session. For a group therapy session, it is recommended to notify each individual before the meeting, since debriefing the last individual can be problematic [13, 15, 20]. Deferring new admissions to the unit, cancelling the admission of high-risk patients, and a higher level of observation have been recommended until the environment is restabilized [6].Responsible staff should use restrictive safety measures with caution, in order not to destabilize the environment further or cause repercussions [9]. Depending on the circumstances, fellow patients may be questioned directly by the police. To avoid secondary trauma, fellow patients may need emotional support [13].

Short-term support

Short-term programs focus on supporting patients with grief. Clinician support should continue for many days or months to alleviate their distress. Listening to their suggestions may improve the care quality for other patients [14, 16]. Healthcare providers should not avoid explaining the event. Avoidance relays a bad message that may cause isolation and prevent support seeking in patients [19]. During the meeting, the clinician should speak of the deceased with respect, avoiding words that can be mistaken for approval or glamorizing the suicide action. Lack of awareness of options, fear, and poor decision making can be mentioned for the explanation of the suicide [14, 16]. The clinician should disregard stigmas that may limit the therapeutic progress of suicidal patients and avoid venerating the dead or minimizing the consequences of their suicidal actions. Instead, the clinician should emphasize suicide as an incorrect decision, while presenting alternative solutions to relieve their pain [20]. The support should be given in such a way that it cannot be accessed outside the therapeutic setting due to stigma and shame [14, 15]. Patients may not feel secure in expressing their griefs and sharing their fears [5]. Minority groups and cultures may have different needs and require a more patient-centered approach [5, 21].

Long-term support

We found no study conducting therapeutic interventions for fellow patients in the long term. In group therapy, leaving the session sooner, being absent, or being late are harmful. Group members may gradually leave the group after a suicide. The remaining members may create a more robust unit [15]. The fellow patients should stay where they can find comfort [16]. In acute health settings, there is an increased potential for acting out. Requests to leave may receive after a suicide in the unit [13]. In one study, members of an online group therapy gave support to each other by sending email, online chat, or through telephone [14]. In another study, group members tried to reduce other members’ feelings of guilt during sessions [19]. Recurrence of a discussion about suicide can happen frequently and may indicate a need for safety [15, 19]. It is common to try to understand the rationale behind the suicide to find some explanation for the act [16]. Fellow patients may want to do something special to commemorate the deceased [16]. It is essential to include the deceased’s family in decisions regarding any planning for commemoration [13]. In one study, patients as the members of an online group therapy made a memorial page as a virtual cemetery for the deceased [14].

Discussion

Psychiatric patients are among the high-risk group for attempted or completed suicide [7]. The psychiatric patients in group therapy or group settings are at a higher risk than other patients to be exposed to suicide. This scoping review study was conducted for understanding the impact of suicide on fellow patients and investigating the interventions for them. The search yielded ten articles and three guidelines (grey literature) that addressed fellow patients. This ranged from a brief report [17] to papers focusing mainly on this topic [16]. There is a lack of evidence in this field. There is some evidence on defining the patients’ relationship with the deceased and the possible use of postvention strategies for the bereaved survivors. However, there is scant research on fellow patients exposed to suicide. Most of the studies have been conducted on suicide survivors with existing guidelines and high-level evidence for effective interventions [5, 8, 16, 22]. This suggests that we should consider whether a fellow patient meets the criteria for a suicide survivor, as they not only exposed to the suicide but also had a personal relationship with the deceased. If we consider fellow patients as suicide survivors, there are clear recommendations for how to reduce distress, pain, and risk in them [5, 6, 8, 11]. If we do not consider them as the bereaved survivors of suicide, the existing literature fails us. We do not know about the impact of suicide on fellow patients. Thus, we may need to refer to studies conducted in non-clinical settings such the military setting [3] to see what measures have been implemented to address those exposed to suicide due to proximity, not due to having relationship with the deceased. The articles reviewed in this study suggested four factors that may affect the impact of suicide on fellow patients: the relationship with the deceased (casual contact vs. close contact ), level of exposure to the suicide event (witnessed vs. informed of), the nature of the suicide (e.g., unexpected, violence, disruption of the social milieu) and the patient’s vulnerability level (e.g., having a history of exposure or suicide attempts, current level of illness). By considering these factors, we can examine the potential impact of suicide and develop a more personalized approach to address the needs of a patient.

This review study has both strengths and limitations. The study followed established methodology and was a robust and replicable review of the current evidence on the subject. We were unable to update the searches due to lack of resources. The review has accurately identified the gap in the existing literature. The focus of this review study on fellow patients limited us to those in clinical settings and excluded some studies conducted in non-clinical settings. The study yielded a limited number of articles with a low level of evidence. The existing literature provides some recommendations for immediate, short-term, and long-term supports. Recommendations for immediate support are mainly focused on the management of acute risk in the clinical setting. Short-term supports are largely limited to anecdotal advice for managing stress, avoiding the exacerbation of existing mental health problems, and providing support for recovery. Common postvention strategies may be applicable to this fellow patients, although there is no existing evidence to support their use. Given the dearth of evidence, robust assessment of patients’ needs and acceptability and efficacy of interventions for different populations exposed to suicide in different health settings remains a priority [5]. Further study is needed to understand which interventions can reduce the adverse outcomes of suicide exposure in fellow patients. To date, no interventional studies have been conducted in this field (Institute of Living. Guidelines for Response: Death by Suicide of a Patient, Accessed July 5 2021 [5], possibly due to the rarity of the event. Finally, we should not neglect the importance of promoting the role of fellow patients in identifying the needs and developing future support recommendations.

Conclusions

There is a lack of study on the impact of suicide on fellow patients and the interventions for them, despite the existence of evidence that psychiatric patients are among high-risk groups for exposure to suicide. The distinction of patients as suicide survivors or those exposed to suicide can allow the application of interventions designed for the suicide survivors on the fellow patients. Further studies are required to identify high-risk groups from among the fellow patients and design effective interventions for the suicide-exposed patients to reduce their distress and risks.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a review study with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Search strategy: Narges Beyraghi, Camellia Srikanthan and Terri Rodak; Study/Source of Evidence selection, Data Extraction: Narges Beyraghi, Camellia Srikanthan, Terri Rodak and Andrea Wddel; Project administration: Narges; Data Analysis and Presentation, review: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

In psychiatric hospitals, fellow patients are at a higher risk of being exposed to the suicide of patients [1]. When a suicide occurs in these settings, the impact on other patients can be high [2] . There is scant research on how the suicides in psychiatric settings can significantly affect the fellow patients [3, 4] Experts believe that a person who is exposed to suicide, regardless of her/his relationship with the deceased, may experience a more complicated and prolonged form of grief [5, 6]. Patient suicide affects those exposed to this event. Each suicide creates 11 victims: the person who died and the 10 caregivers, family, and friends [7]. There is a distinction between “suicide survivorship” and “exposure to suicide”. The first refers to the one who had a personal and close relationship with the deceased. The second refers to a situation where a person with no close relationship with the deceased was indirectly informed about the death or witnessed the death of a stranger [8]. Fellow patients may have different types of relationships in clinical settings that can affect the aftermath of a suicide. Patients in group therapies and peer support groups are examples of patients who may have stronger relationships with each other [6, 9]. On the other hand, acute care settings usually provide services to more vulnerable patients with mental health problems, history of suicidal thoughts or attempts, or psychosocial disorders [6]. Despite the existence of evidence about the risk of a suicide in other groups with close relationships, there is a limited information about the risk of suicide among fellow patients in a clinical setting [8].

Suicide is a traumatic event. Suicide bereavement is associated with trauma and grief. Being exposed to suicide leads to higher rates of suicidal thoughts in the bereaved, regardless of the type of relationship with the deceased [10]. Postvention is essential in these situations and can be life-saving. Postvention strategies refer to activities after a suicide for destigmatizing suicide and promoting recovery in the bereaved survivors. Current studies have primarily focused on suicide prevention and risk assessment, and not on the aftermath of suicide. The literature have indicated a high and persistent risk for adverse sequelae in the bereaved survivors even 10 years after suicide [1]. Clinical postvention strategies for fellow patients should address their recovery process to remove the stigma associated with suicide and act as secondary prevention to reduce the risks of suicide in them [11].

There is a scant research on the effects of suicide on fellow patients and the use of post-suicide interventions for these people. Gaining information about the postvention protocols can enhance the quality of care for these people. Therefore, this scoping review study aims to systematically analyze the current evidence on the postvention strategies and the aftermatch of suicide in a clinical setting on the fellow patients . The objectives of this review study are as following:

1. Surveying the experiences of fellow patients of after a suicide;

2. Investigating the interventions available to fellow patients after a suicide;

3. Providing recommendations for the support of the bereaved.

Materials and Method

This is a scoping review study using The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis: Development of a Scoping Review Protocol [12]. The research team discussed and revised the protocol based on feedback. The final protocol was prepared on November 15, 2020. The articles published from 2000 to 2020 in English, grey literature (e.g., reports, theses, unpublished research materials, newspapers, website materials, and policy papers), qualitative and quantitative studies in clinical settings (hospital or community health centers), the studies on the impact of suicide on fellow patients containing information on post-suicide interventions were included in the search. The articles not available in English, those focused only on the bereaved individuals who fellow patients (e.g., family members, health care providers), those conducted only on children and adolescents, those only about suicide prevention or suicide risk assessment, book chapters, and conference abstracts were excluded.

The search was conducted using subject headings and keywords in the following databases: Medline, Embase, APA PsycInfo, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. A medical librarian (TR) developed the search strategies and conducted searches on December 22, 2020. The keywords related to the patient suicide included «suicide», «intentional overdose», «self-inflicted» combined with terms used for psychiatric settings and patients such as «psychiatric hospitals», «community mental health services», «inpatients». The keywords related to the bereaved survivors included «therapeutic community», «group psychotherapy», and «group member», “institutional policies”, “response protocol”, and “postvention. For related grey literature, the search was conducted by Google and Google Scholar engines using the following terms: «co-patient», «other patients», «fellow patient», «inpatient», «suicide», and «postvention». The first five pages of results for each query were examined for relevant materials. The references of the found articles were also checked to ensure no relevant articles were missed. We also contacted the relevant organizations by email to inquire if additional information can be added to clarity to the search results. The following organizations were contacted: Mental Health Commission of Canada, the Royal Mental Health Care & Research, the Cochrane Consumer Network, the National Institute of Mental Health, Campbell Collaboration, and the World Health Organization (WHO). The information provided by the organizations related to suicide prevention efforts rather than postvention methods were not included in the review.

The list of the found articles was imported into the Covidence website to screen their titles, abstracts, and subsequently full-texts. The duplicate articles were removed before screening the titles and abstracts. Two authors (NB, AW) independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility and had a group discussion to resolve any conflicts identified on Covidence. Two authors (NB,CS) later screened the full texts independently and discussed the conflicts that needed to be resolved until a final decision was made on which articles should be included in the data extraction stage. Two authors (NB, CS) independently completed the data extraction from the full texts and compared the details until a consensus was reached. Figure 1 presents the summary of the screening process. JBI’s critical appraisal checklist was used for the quality assessment of studies (Table 1).

The extracted data included authors’ information (name, affiliations, country, study area), study populations, methodology, and findings. A summary of this information is provided in Table 2.

Results

Fellow patients’ experiences with suicide

Eight articles described fellow patients’ experience after a suicide event. Three sub-themes were thus identified: Emotional responses to the suicide, Clinical symptoms as the aftermath of the suicide, and suicide contagion and suicide management.

Emotional responses to the suicide

When a suicide happens in a therapeutic setting, other patients may show different emotional reactions. Three articles described fellow patients’ feelings of shock, disbelief, denial, confusion, disorientation, guilt, and sadness following a suicide [3, 13, 14]. One article provided information on fellow patients’ reactions that were more specific to suicide from a psychodynamic perspective [15]. Four articles describe fellow patients’ reactions that were more specific to the suicide event. Two articles described how fellow patients experienced feelings of abandonment and anger towards the deceased. Asking other patients with a similar experience for support was reported in group therapy settings. Identifying the suicide victim and seeing the worst outcome as inevitable were reported as early reactions [16]. Seeking for answers can lead to self-blaming and rumination about the deceased [5]. One article reported that fellow patients held the medical staff responsible for not preventing the suicide. This article suggested that anger towards health care providers may be the presentation of displaced anger at the person who committed suicide [3]. The accusation of other fellow patients and medical staff were also been reported as the aftermath of suicide [6].

Clinical symptoms

Post-suicide mental health problems result from the interaction between the events, the type of relationship with the suicide victim, and the vulnerability or resilience of the fellow patient [16, 17]. Factors that further cause clinical symptoms include poor psychosocial support, history of trauma or recent loss, psychological disorders, chronic diseases, and history of suicide attempt [6, 18]. Studies reported somatic symptoms, intrusive flashback memories, increased anxiety, tension, psychological arousal, and poor sleep quality in affected fellow patients [3, 15, 16]. Depressive symptoms may start after the suicide and become a complete depressive episode one month after the suicide, and can persist for several months [6, 15, 19]. Patients exposed to suicide experienced symptoms as an acute stress reaction such as dissociative episodes, hypervigilance, and poor sleep quality [3, 16]. In one study, a fellow patient who found the deceased reported an inability to sleep due to seeing the deceased’s face when closing his eyes [3]. Development of homicidal ideation and exacerbation of psychotic symptoms were also reported in some studies [3, 15, 16]. In one study, a fellow patient who was experiencing pathological denial accused another member of homicide [3]. Patients who are actively psychotic may have delusional thoughts about the suicide or claim responsibility, reporting some relationship with an imagined aggressor, or believe that they caused the suicide [13].

Suicide contagion and suicide management

Relationship with the deceased and the desire to emulate their actions was reported in four studies [3, 13, 14, 16].The suicidal thoughts of fellow patients may intensify their anxiety about being at risk for suicide [13]. Being emotionally close to the suicide victim and having a history of self-harm are risk factors of suicide contagion [3, 16]. Being a psychiatric patient can cause multiple exposures to suicide. Each suicide event have a cumulative impact, which can increase the possibility of adverse reaction when exposed to suicide [5]. Suicide contagion is mainly considered as a short-term response, and the pain caused by exposure in the long term may have a restraining effect [6]. Limited information exist about the fellow patients’ long-term reaction to suicide. Two articles examined long-term responses during a group therapy, reporting that the suicide thoughts decrease over time, although the event is still mentioned on its anniversary [14, 15].

Suicide postvention for fellow patients

Those exposed to suicide require immediate, short-term, and long-term supports.

Immediate support

Immediate reactions to suicide mainly include self-destructive behaviors and acute reactions. It is essential to develop a clear and structured plan for its management, while avoiding emotional and overreacting responses [3, 9]. Suicides that occur within an inpatient unit necessitate the careful monitoring of patients with active suicidal ideation. These patients can benefit from more intensive individual support services [3, 13, 18]. An experienced clinician needs to provide an accurate description of the suicide event to other inpatients [9]. This description should respect the confidentiality of the deceased, and be tailored based on the conditions of fellow patients. Withholding information from other patients is a very conservative approach for keeping the privacy rights of the deceased, and is unfeasible if the information has already spread. Debriefing is a good way to help patients and prevent the spread of rumors in the absence of accurate information [13]. It can facilitate health-related discussions and requesting support from experienced medical staff [9, 16, 20]. Before having a debriefing session with fellow patients, a staff is needed to coordinate the responses, during which the team decide if external support is needed [9, 14]. Debriefing sessions are recommended to assess each patient’s needs, in addition to providing information. One of the goals of this method is to address the patients’ anxiety and consider safety concerns, even though other discussions may emerge. The medical team needs to decide whether individual support or group support is a better to address the varying needs of patients in each unit. Different conversations may arise during the debriefing that may be difficult to manage in a group session. For a group therapy session, it is recommended to notify each individual before the meeting, since debriefing the last individual can be problematic [13, 15, 20]. Deferring new admissions to the unit, cancelling the admission of high-risk patients, and a higher level of observation have been recommended until the environment is restabilized [6].Responsible staff should use restrictive safety measures with caution, in order not to destabilize the environment further or cause repercussions [9]. Depending on the circumstances, fellow patients may be questioned directly by the police. To avoid secondary trauma, fellow patients may need emotional support [13].

Short-term support

Short-term programs focus on supporting patients with grief. Clinician support should continue for many days or months to alleviate their distress. Listening to their suggestions may improve the care quality for other patients [14, 16]. Healthcare providers should not avoid explaining the event. Avoidance relays a bad message that may cause isolation and prevent support seeking in patients [19]. During the meeting, the clinician should speak of the deceased with respect, avoiding words that can be mistaken for approval or glamorizing the suicide action. Lack of awareness of options, fear, and poor decision making can be mentioned for the explanation of the suicide [14, 16]. The clinician should disregard stigmas that may limit the therapeutic progress of suicidal patients and avoid venerating the dead or minimizing the consequences of their suicidal actions. Instead, the clinician should emphasize suicide as an incorrect decision, while presenting alternative solutions to relieve their pain [20]. The support should be given in such a way that it cannot be accessed outside the therapeutic setting due to stigma and shame [14, 15]. Patients may not feel secure in expressing their griefs and sharing their fears [5]. Minority groups and cultures may have different needs and require a more patient-centered approach [5, 21].

Long-term support

We found no study conducting therapeutic interventions for fellow patients in the long term. In group therapy, leaving the session sooner, being absent, or being late are harmful. Group members may gradually leave the group after a suicide. The remaining members may create a more robust unit [15]. The fellow patients should stay where they can find comfort [16]. In acute health settings, there is an increased potential for acting out. Requests to leave may receive after a suicide in the unit [13]. In one study, members of an online group therapy gave support to each other by sending email, online chat, or through telephone [14]. In another study, group members tried to reduce other members’ feelings of guilt during sessions [19]. Recurrence of a discussion about suicide can happen frequently and may indicate a need for safety [15, 19]. It is common to try to understand the rationale behind the suicide to find some explanation for the act [16]. Fellow patients may want to do something special to commemorate the deceased [16]. It is essential to include the deceased’s family in decisions regarding any planning for commemoration [13]. In one study, patients as the members of an online group therapy made a memorial page as a virtual cemetery for the deceased [14].

Discussion

Psychiatric patients are among the high-risk group for attempted or completed suicide [7]. The psychiatric patients in group therapy or group settings are at a higher risk than other patients to be exposed to suicide. This scoping review study was conducted for understanding the impact of suicide on fellow patients and investigating the interventions for them. The search yielded ten articles and three guidelines (grey literature) that addressed fellow patients. This ranged from a brief report [17] to papers focusing mainly on this topic [16]. There is a lack of evidence in this field. There is some evidence on defining the patients’ relationship with the deceased and the possible use of postvention strategies for the bereaved survivors. However, there is scant research on fellow patients exposed to suicide. Most of the studies have been conducted on suicide survivors with existing guidelines and high-level evidence for effective interventions [5, 8, 16, 22]. This suggests that we should consider whether a fellow patient meets the criteria for a suicide survivor, as they not only exposed to the suicide but also had a personal relationship with the deceased. If we consider fellow patients as suicide survivors, there are clear recommendations for how to reduce distress, pain, and risk in them [5, 6, 8, 11]. If we do not consider them as the bereaved survivors of suicide, the existing literature fails us. We do not know about the impact of suicide on fellow patients. Thus, we may need to refer to studies conducted in non-clinical settings such the military setting [3] to see what measures have been implemented to address those exposed to suicide due to proximity, not due to having relationship with the deceased. The articles reviewed in this study suggested four factors that may affect the impact of suicide on fellow patients: the relationship with the deceased (casual contact vs. close contact ), level of exposure to the suicide event (witnessed vs. informed of), the nature of the suicide (e.g., unexpected, violence, disruption of the social milieu) and the patient’s vulnerability level (e.g., having a history of exposure or suicide attempts, current level of illness). By considering these factors, we can examine the potential impact of suicide and develop a more personalized approach to address the needs of a patient.

This review study has both strengths and limitations. The study followed established methodology and was a robust and replicable review of the current evidence on the subject. We were unable to update the searches due to lack of resources. The review has accurately identified the gap in the existing literature. The focus of this review study on fellow patients limited us to those in clinical settings and excluded some studies conducted in non-clinical settings. The study yielded a limited number of articles with a low level of evidence. The existing literature provides some recommendations for immediate, short-term, and long-term supports. Recommendations for immediate support are mainly focused on the management of acute risk in the clinical setting. Short-term supports are largely limited to anecdotal advice for managing stress, avoiding the exacerbation of existing mental health problems, and providing support for recovery. Common postvention strategies may be applicable to this fellow patients, although there is no existing evidence to support their use. Given the dearth of evidence, robust assessment of patients’ needs and acceptability and efficacy of interventions for different populations exposed to suicide in different health settings remains a priority [5]. Further study is needed to understand which interventions can reduce the adverse outcomes of suicide exposure in fellow patients. To date, no interventional studies have been conducted in this field (Institute of Living. Guidelines for Response: Death by Suicide of a Patient, Accessed July 5 2021 [5], possibly due to the rarity of the event. Finally, we should not neglect the importance of promoting the role of fellow patients in identifying the needs and developing future support recommendations.

Conclusions

There is a lack of study on the impact of suicide on fellow patients and the interventions for them, despite the existence of evidence that psychiatric patients are among high-risk groups for exposure to suicide. The distinction of patients as suicide survivors or those exposed to suicide can allow the application of interventions designed for the suicide survivors on the fellow patients. Further studies are required to identify high-risk groups from among the fellow patients and design effective interventions for the suicide-exposed patients to reduce their distress and risks.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a review study with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Search strategy: Narges Beyraghi, Camellia Srikanthan and Terri Rodak; Study/Source of Evidence selection, Data Extraction: Narges Beyraghi, Camellia Srikanthan, Terri Rodak and Andrea Wddel; Project administration: Narges; Data Analysis and Presentation, review: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Walsh G, Sara G, Ryan CJ, Large M. Meta-analysis of suicide rates among psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015; 131(3):174-84. [DOI:10.1111/acps.12383] [PMID]

- Cazares PT, Santiago P, Moulton D, Moran S, Tsai A. Suicide response guidelines for residency trainees: A novel postvention response for the care and teaching of psychiatry residents who encounter suicide in their patients. Acad Psychiatry. 2015; 39(4):393-7. [DOI:10.1007/s40596-015-0352-7] [PMID]

- Carr RB. When a soldier commits suicide in Iraq: Impact on unit and caregivers. Psychiatry. 2011; 74(2):95-106. [DOI:10.1521/psyc.2011.74.2.95] [PMID]

- Lin SK, Hung TM, Liao YT, Lee WC, Tsai SY, Chen CC, et al. Protective and risk factors for inpatient suicides: A nested case-control study. Psychiatry Res. 2014; 217(1-2):54-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.008] [PMID]

- Maple M, Poštuvan V, McDonnell S. Progress in postvention. Crisis. 2019; 40(6):379-82. [DOI:10.1027/0227-5910/a000620] [PMID]

- Sakinofsky, I. The aftermath of suicide: Managing survivors’ bereavement. Can J Psychiatry. 2007; 52(6 Suppl 1):129S - 36S. [Link]

- Insel T. A new research agenda for suicide prevention [Internet]. 2014 [Updated 2014 March 07]. Available from: [Link]

- Andriessen K, Krysinska K. Essential questions on suicide bereavement and postvention.Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012; 9(1):24-32. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph9010024] [PMID]

- Ballard ED, Pao M, Horowitz L, Lee LM, Henderson DK, Rosenstein DL. Aftermath of suicide in the hospital: Institutional response. Psychosomatics. 2008; 49(6):461-9. [DOI:10.1176/appi.psy.49.6.461] [PMID]

- Jordan JR. Postvention is prevention-The case for suicide postvention. Death Stud. 2017; 41(10):614-21. [DOI:10.1080/07481187.2017.1335544] [PMID]

- Erlich MD, Rolin SA, Dixon LB, Adler DA, Oslin DW, Levine B, et al. Why we need to enhance suicide postvention: Evaluating a survey of psychiatrists’ behaviors after the suicide of a patient. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017; 205(7):507-11. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000682] [PMID]

- Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, Leatherdale ST. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst Rev. 2015; 4:138. [DOI:10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0] [PMID]

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) CAMH: Suicide prevention and assessment handbook. Toronto: CAMH; 2018. [Link]

- Hsiung RC. A suicide in an online mental health support group: Reactions of the group members, administrative responses, and recommendations. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007; 10(4):495-500.[DOI:10.1089/cpb.2007.9999] [PMID]

- Gafford JR. The impact of a suicidal individual on group therapy: A phenomenological study of group leaders’ experiences [PhD dissertation]. Denver: University of Denver; 2008. [Link]

- Seeman MV. The impact of suicide on co-patients. Psychiatr Q. 2015; 86(4):449-57. [DOI:10.1007/s11126-015-9346-6] [PMID]

- Campbell C, Fahy T. The role of the doctor when a patient commits suicide. Psychiatr Bull. 2002; 26(2):44-9. [DOI:10.1192/pb.26.2.44]

- New Zealand Psychologists Board. Best practice guideline: Coping with a Client Suicide. Wellington: New Zealand Psychologists Board; 2017.

- O’Neill SM, Kueppenbender K. Suicide in group therapy: Trauma and possibility. Int J Group Psychother. 2012; 62(4):586-611. [Link]

- Sung JC. Sample Agency practices for responding to client suicide [Internet]. 2016 [Updated 21 March 2016]. [Link]

- Institute of Living. Guidelines for response: Death by suicide of a patient. Hartford: Institute of Living; 2017. [Link]

- Andriessen K, Krysinska K, Kõlves K, Reavley N. Suicide postvention service models and guidelines 2014-2019: A systematic review. Front Psychol. 2019; 10:2677. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02677] [PMID]

Type of Study: review |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2023/05/6 | Accepted: 2023/07/1 | Published: 2023/07/1

Received: 2023/05/6 | Accepted: 2023/07/1 | Published: 2023/07/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |