Sat, Nov 22, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 1, Issue 4 (Summer 2023)

CPR 2023, 1(4): 432-449 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Soltani M, Salehi B, Kheirabadi G. Relationship Between Perfectionism and Binge Eating Disorder in Female College Students: The Mediating Role of Distress Tolerance. CPR 2023; 1 (4) :432-449

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-48-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-48-en.html

Department of Psychiatry, Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 2739 kb]

(437 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1609 Views)

Full-Text: (488 Views)

Introduction

Eating disorders are known as one of the common psychosomatic problems [1] that play a role in a wide range of issues related to mental health and are more prevalent among people aged 20-40 years [2]. Eating disorders are characterized by persistent disturbances in eating and related behaviors that cause changes in food consumption or absorption and are also significantly associated with damage to physical or psychological functioning [3]. According to the fifth edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5), these disorders include pica, rumination disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder (BED), and unspecified eating disorder [4]. Guerdjikova et al. [5] considered BED to be the most common eating disorder and stated that this disorder is usually neglected in both males and females, and affected people are not treated. According to the DSM-5 criteria, the lifetime prevalence of BED is 0.9%, and its 12-month prevalence is 0.4% [6]. Eating disorders are more common in females, such that in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, the ratio of female to male is 9:1, and in BED, the ratio is 6:4 [7]. Evidence showed that BED is equally common in male and female Iranian college students, although gender differences were also observed in some components [8]. Eating disorders, especially BED, is associated with unpleasant consequences such as obesity [9], depression, anxiety [10], suicide [11], and drug use [12]. There are also other variables as predictors of BED, the most important of which are the idealization of thinness and body dissatisfaction [13]. Regarding the etiology of BED, various factors including biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors have been implicated [14]. Among the psychological factors, the role of perfectionism in the formation of BED has been emphasized in some studies [15، 16]. Some studies have shown that the direct effect of perfectionism on eating disorders is not significant, but perfectionism is related to eating disorders by creating negative moods and especially depression [10]. In addition, some studies reported that distress tolerance can play a mediating role between perfectionism and eating disorders [16-18, 19]. These studies on the link between perfectionism and eating disorders are about trait perfectionism. In our study, perfectionism is studied in the form of two types: Adaptive and non-adaptive. In addition, most of these studies have been conducted in the United States or Canada, and not in Iran. Since the results of perfectionism may be influenced by socio-cultural factors, the present study was carried out in Iran. The results of some studies indicated a significant and strong relationship between perfectionism and distress tolerance [20، 21]. People with eating disorders show lower distress tolerance [18, 23-24]. The sum of these findings makes this research hypothesis that the relationship between perfectionism and eating disorders can be indirect and through other variables such as distress tolerance.

Distress tolerance is defined as a person’s ability to experience and tolerate negative emotional states. In fact, distress tolerance is an individual factor that refers to the capacity to withstand emotional distress [25]. It is considered a proxy for strengthening positive reactions in stressful situations [26]. Low levels of distress tolerance make a person vulnerable to many psychological injuries [27]. Distress tolerance appears in two forms; one form refers to a person’s ability to tolerate negative emotions, and the other is the behavioral manifestation of tolerating unpleasant internal states caused by various stressful situations [28]. People with low distress tolerance engage in disorganized behaviors in a wrong attempt to deal with their negative emotions [29]. By engaging in some harmful behaviors such as consuming drugs, alcohol, and excessive foods, they try to relieve their emotional pain, which leads to their temporary relief from negative emotions [30]. The results of studies indicated that distress tolerance is related to both perfectionism and BED [16-18، 31]. Previous studies on low distress tolerance, emotion regulation difficulties, and eating disorders have mainly conceptualized emotion dysregulation as broad problems related to the perception of emotional experiences, the use of flexible strategies, and the tolerance of negative emotions. For example, it was shown that anorexia nervosa in healthy students is associated with increased difficulties in cognitive emotion regulation, including limited access to adaptive cognitive emotion regulation skills [32]. There is limited attention to the ability to tolerate distress. Previous studies suggest frequent use of observed variables, which neglect potential measurement errors that can obscure true interactive correlations [33]. For example, inconsistent findings on the relationship between perfectionism and eating disorders can be due to random measurement errors in observed variables. These errors may have similarly influenced the true interaction effects of perfectionism and distress tolerance on eating disorders. Therefore, the need to use more accurate methods such as structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate hidden and mediating variables is evident. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the relationship between perfectionism and BED in female college students mediated by distress tolerance.

Methods

This is a descriptive-correlational study using SEM. The study population consists of all female college students in Isfahan, Iran, of whom 214 were selected as the samples. The sample size was determined using the formula proposed by Kline [34]; by considering 20 participants for each parameter, the sample size was determined 180, but given the possible sample drop and the incompleteness of some questionnaires, it was increased to 214. After explaining the study objectives to the participants and obtaining informed consent from them, they were asked to complete the perfectionism inventory (PI), distress tolerance scale (DTS), and binge eating scale (BES).

The BES was developed by Gormally et al. [35] to measure the severity of BED in obese people. It has 16 items rated on a scale from 0 to 3. The total score ranges from 0 to 46; a score of 16 indicates a BED, and a score >16 shows severe BED. The split-half reliability, test re-test reliability, and internal consistency of the Persian version of BES have been reported as 0.67, 0.72, and 0.85 [36].

The DTS was developed by Simons and Gaher [26] as a self-report tool for measuring distress tolerance. It has 15 items and four subscales of tolerance, absorption, appraisal, and regulation. The items are rated on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to five (strongly disagree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of distress tolerance. The α coefficients for the subscales of DTS are 0.72, 0.82, 0.78, and 0.70, respectively. For the whole scale, it is 0.82. The intraclass correlation coefficient for a six-month interval was 0.61. Also, the discriminant validity of this scale by assessing its relationship with the negative and positive affect subscales of the general temperament survey [37] was reported as 0.59 and 0.26, respectively [26]. Cronbach’s α of the Persian DTS has been reported as 0.67, and its test re-test reliability is 0.79 [38] .

The PI was developed by Hill et al. [39] with 59 items to measure eight different dimensions of perfectionism including “concern over mistakes,” “high standards for others,” “need for approval,” “organization,” “parental pressure,” “planfulness,” “rumination,” and “striving for excellence.” For scoring, it uses a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The internal consistency using Cronbach’s α for the components ranges from 0.83 to 0.91 [39]. For the Persian, the α is 0.91 for the whole scale. For the components, it ranges from 0.69 to 0.85 [40]. The test re-test reliability for a one-month interval was 0.73 [40]. The construct validity was also examined using exploratory factor analysis. The results indicated a 6-factor model of the Persian PI; these 6 factors were able to predict 45% of the total variance [40].

The collected data were analyzed in AMOS software, version 22 using SEM. The mediating role of distress tolerance was measured based on Baron & Kenny’s method.

Results

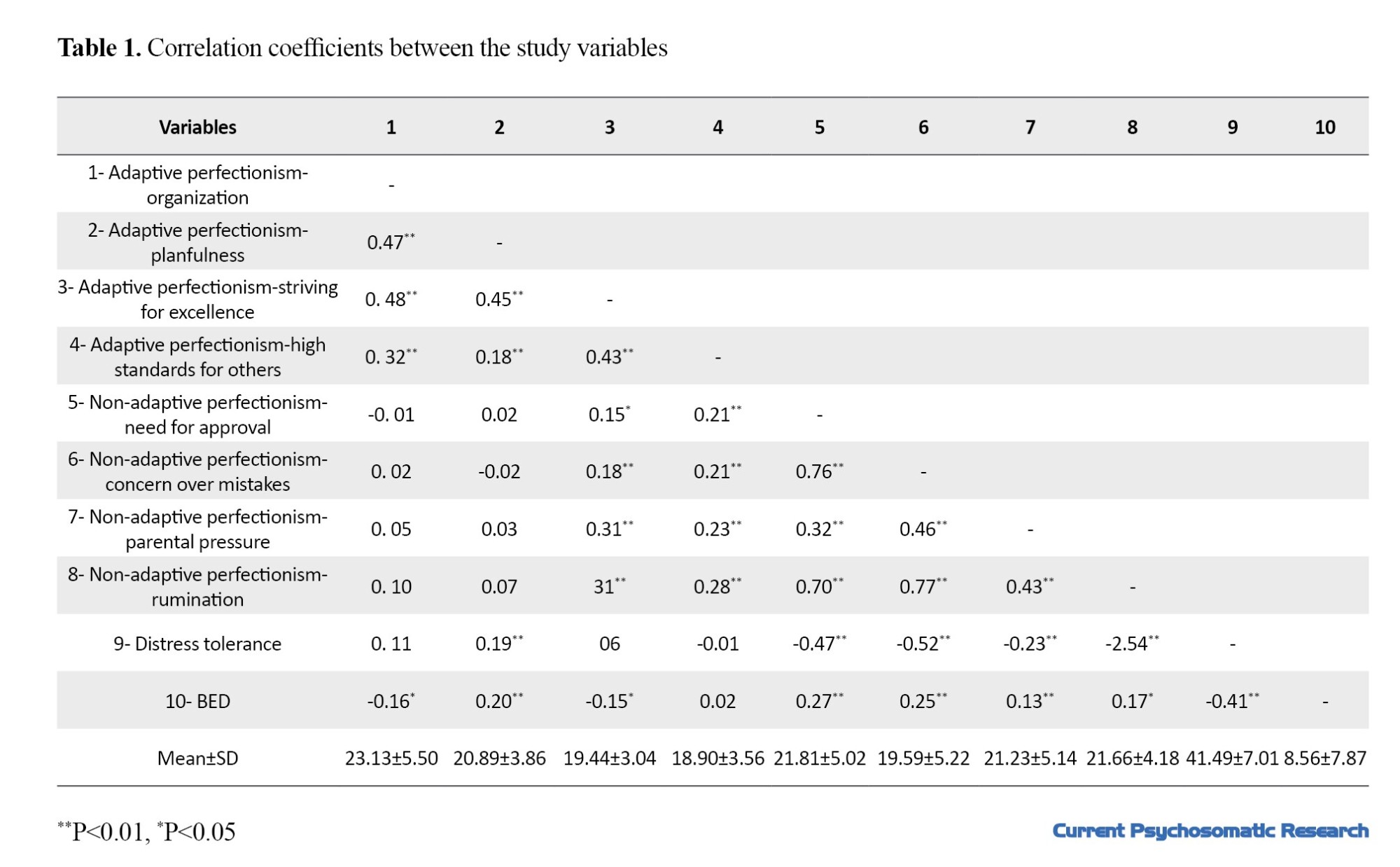

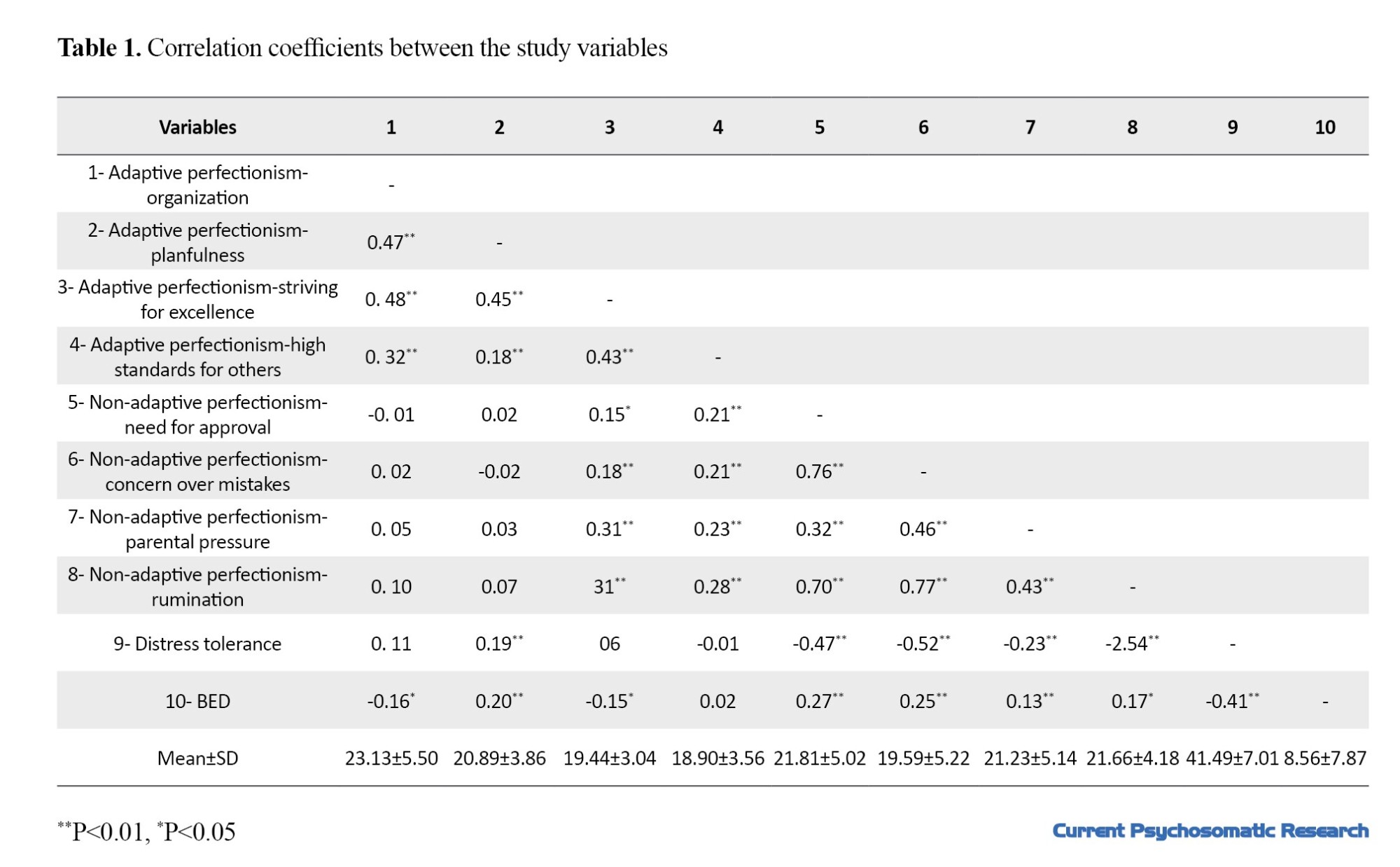

Participants were 167 single female students (77.3%) and 49 married female students (22.7%) with a mean age of 23.61±4.75 years. Among the participants, 31(14.4%) were studying for an associate degree, 131(60.6%) for a bachelor’s degree, 42(19.4%) for a master’s degree, and 12(5.6%) for a PhD degree. Table 1 shows the Mean±SD of the scores and the correlation coefficients between adaptive perfectionism, maladaptive perfectionism, distress tolerance, and BED. As can be seen, among the components of adaptive perfectionism, organization and striving for excellence were negatively correlated with BED (P<0.05), while planfulness was negatively correlated (P<0.01). Among the components of non-adaptive perfectionism, the need for approval (P<0.01), concern over mistakes (P<0.01), parental pressure (P<0.05), and rumination (P<0.05) were positively correlated with BED. Distress tolerance was negatively correlated with BED (P<0.01).

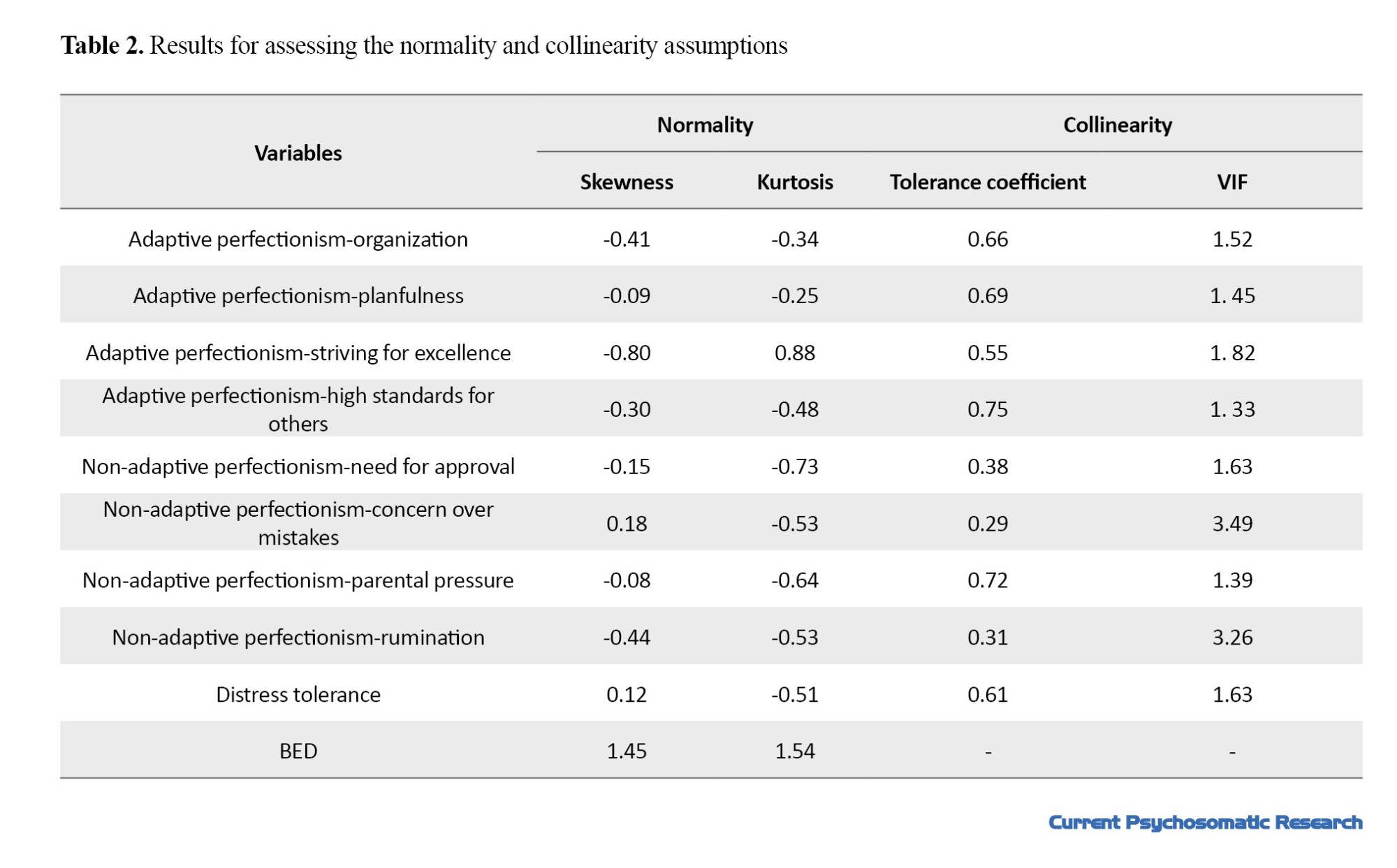

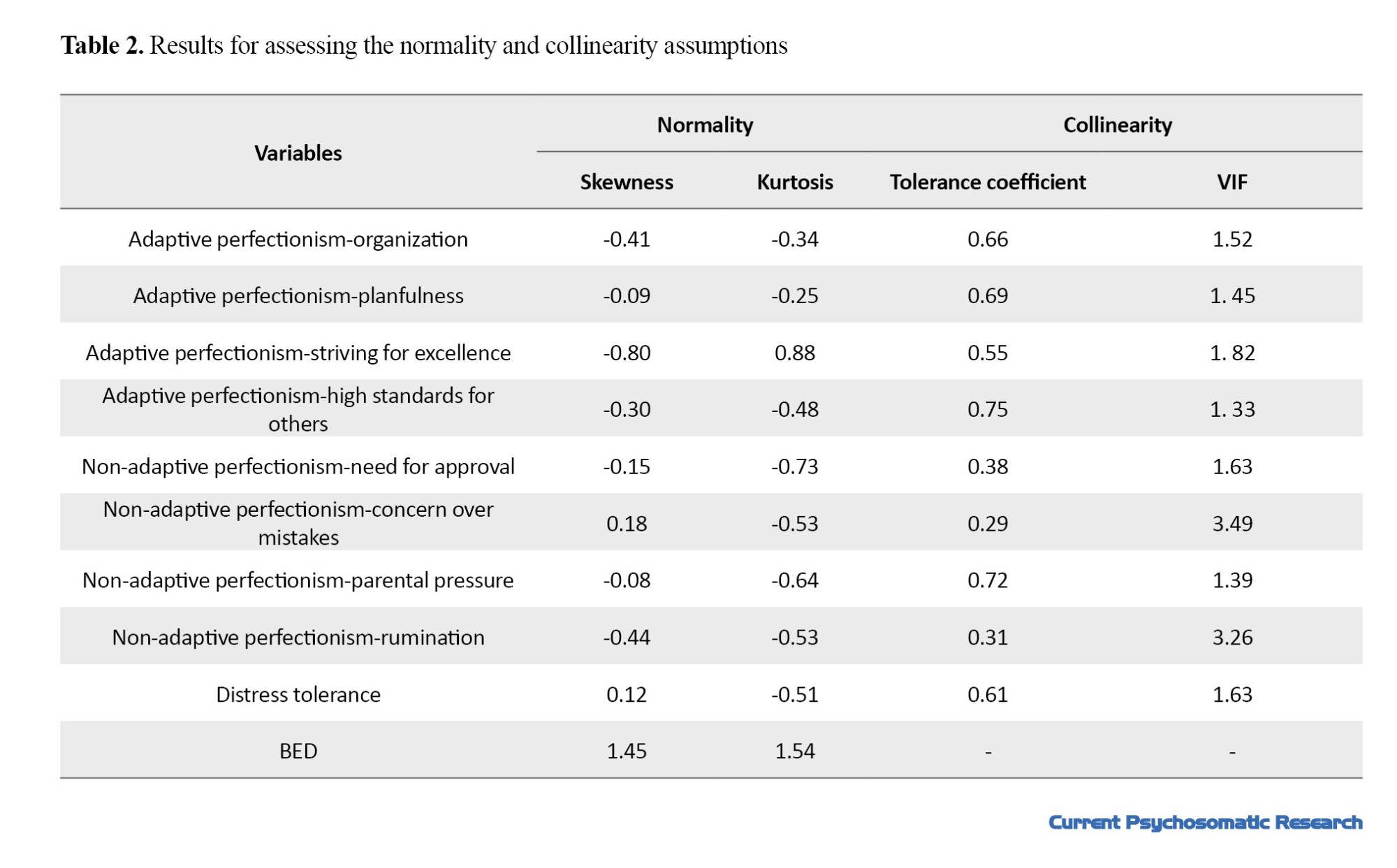

To evaluate the normality of the data distribution, the skewness and kurtosis of the variables, and the assumption of collinearity, the values of variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance coefficient were measured. The results are presented in Table 2. As can be seen, the skewness and kurtosis values of all variables were in the range of ±2, indicating that the assumption of normality of data distribution is confirmed. Moreover, the tolerance coefficient values variables were greater than 0.1 and their VIF values were less than 10. Therefore, the assumption of collinearity was also confirmed. The Mahalanobis distance and the scatterplot of standardized residuals showed that the normality of multivariate data distribution and homogeneity of variances were also established.

The fit of the measurement model was evaluated using the confirmatory factor analysis method in AMOS software, version 24.

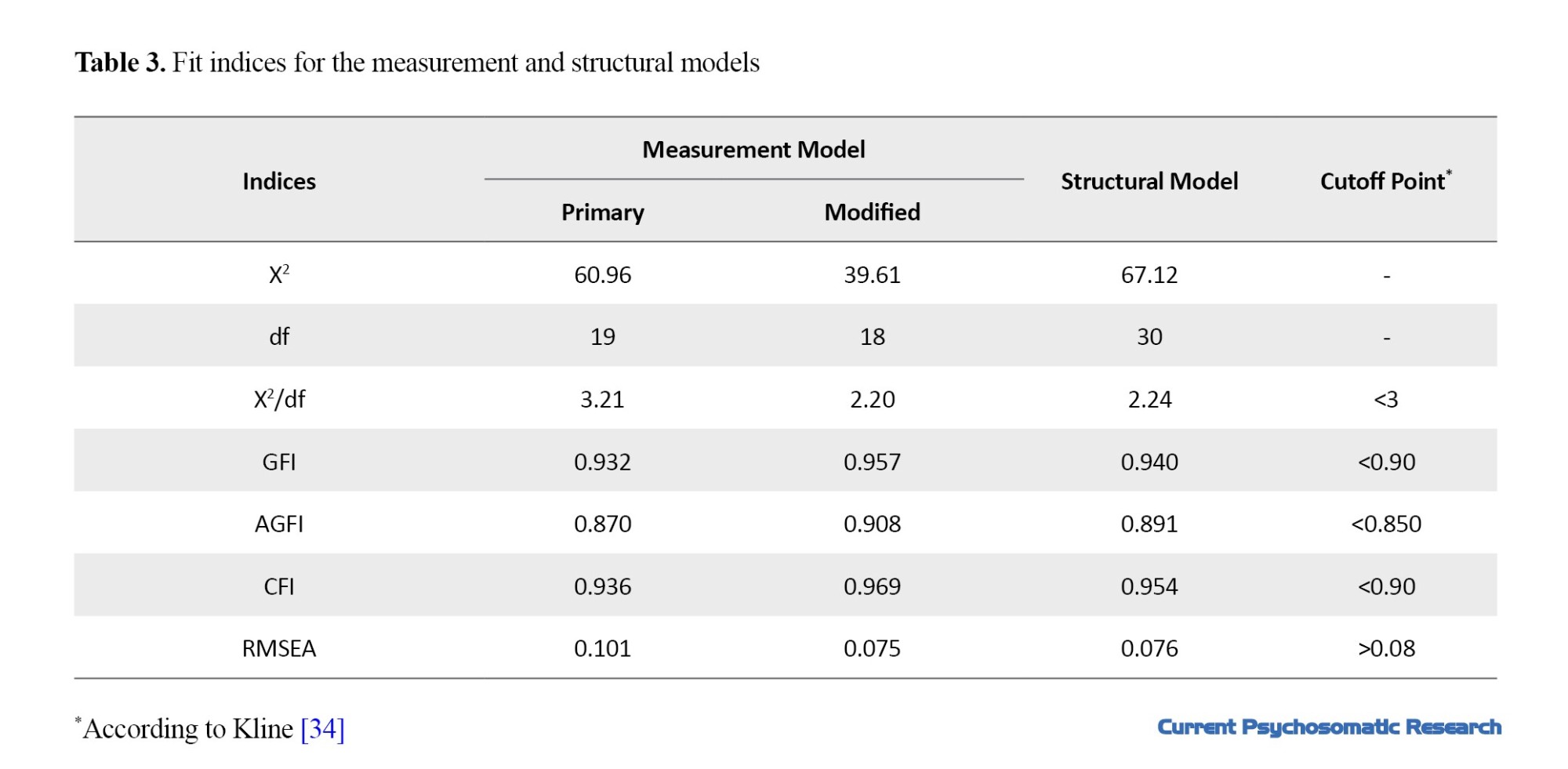

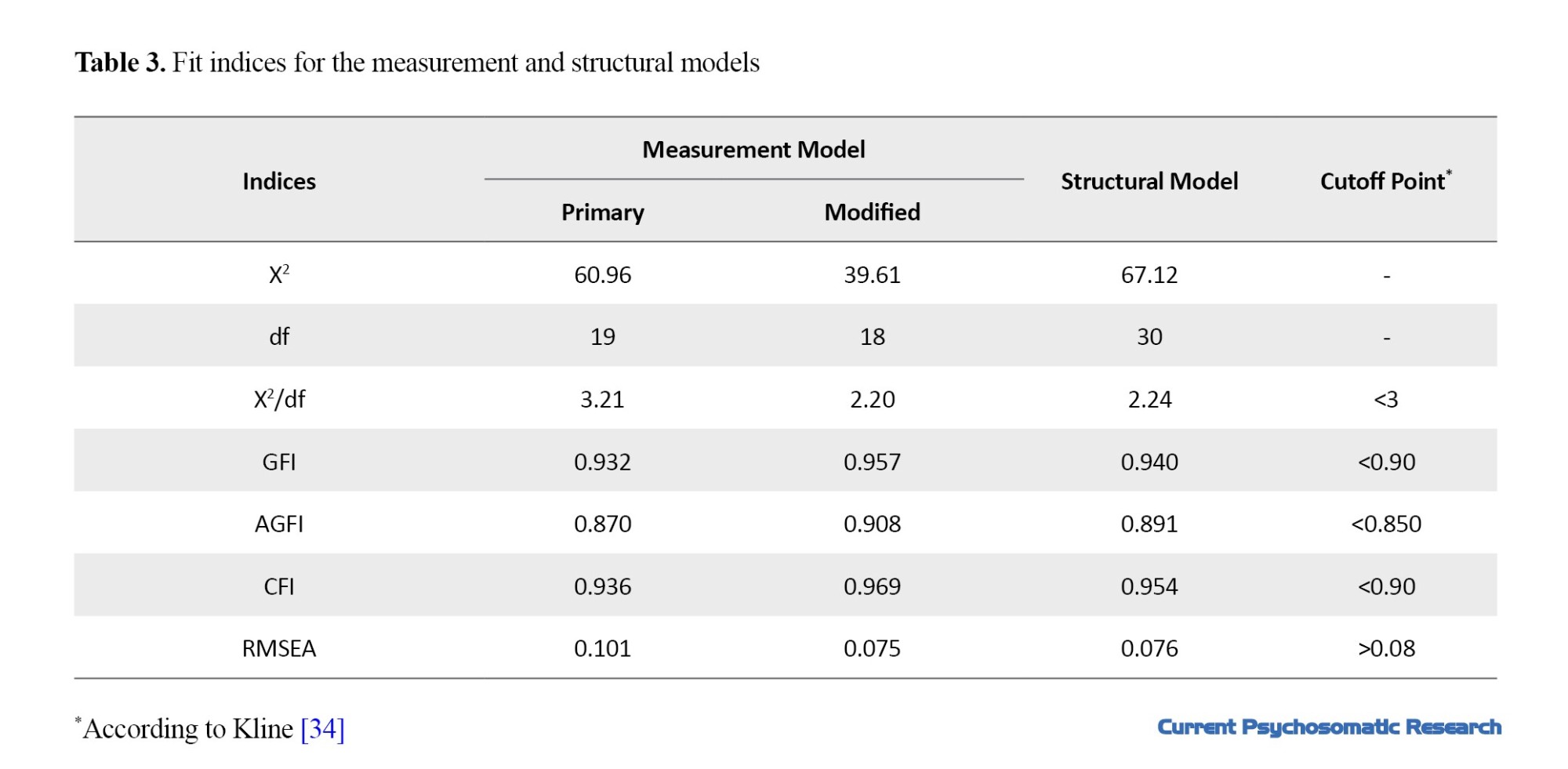

It was assumed that adaptive perfectionism is measured by indicators of organization, planfulness, striving for excellence, and high standards for others, while maladaptive perfectionism is measured by indicators of need for approval, concern on mistakes, parental pressure, and rumination. Table 3 shows the fit indices of the measurement model and the structural model. The results show the acceptable fit of the measurement model (primary and modified) to the collected data. Due to the importance of the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) index, the measurement model was modified by creating a covariance between the errors of the indicators of striving for excellence and parental pressure.

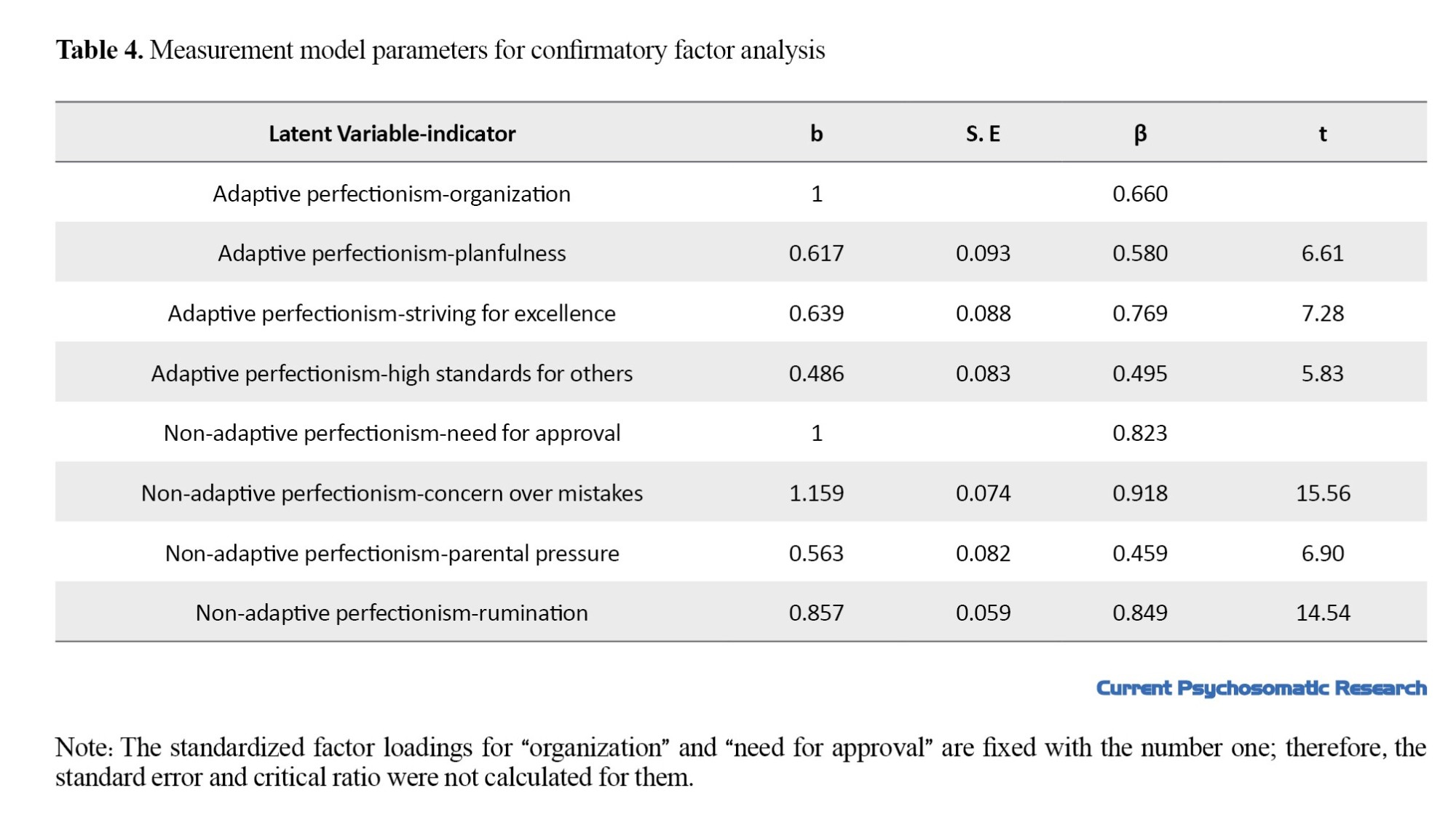

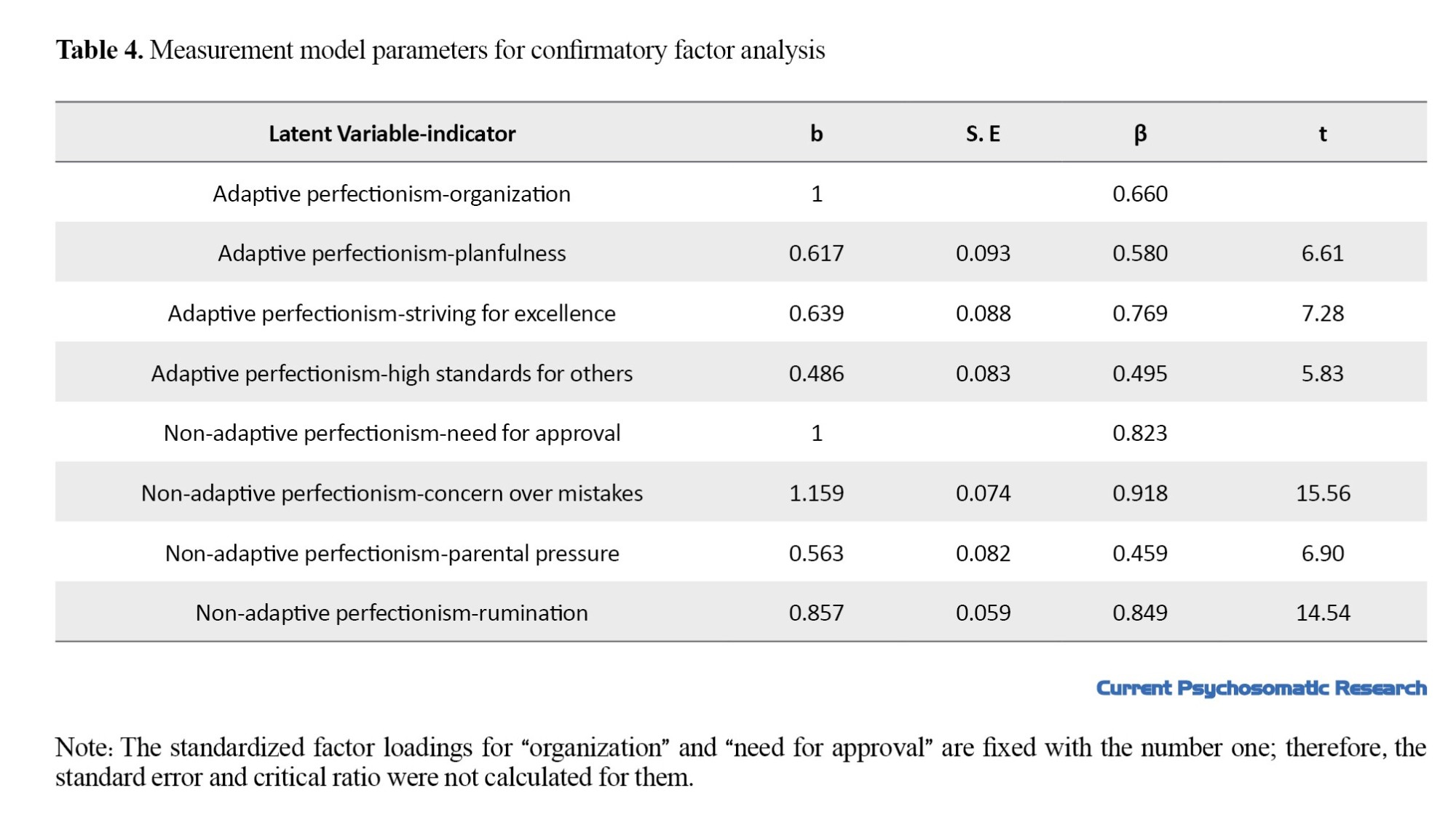

Table 4 shows the standardized and unstandardized factor loadings, standardized error, and critical ratio. As can be seem, the highest factor load belonged to the indicator of concern over mistakes (β=0.918) while the lowest factor load belonged to the indicator high standards for others (β=0.459). Considering that the factor loadings of all indicators were higher than 0.32, it can be said that all indicators had the necessary power to measure the latent variables. In the structural model of the study, it was assumed that adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism predicts BED directly and through the emotional distress tolerance. The results in Table 4 showed that the acceptable fit of the structural model to the collected data.

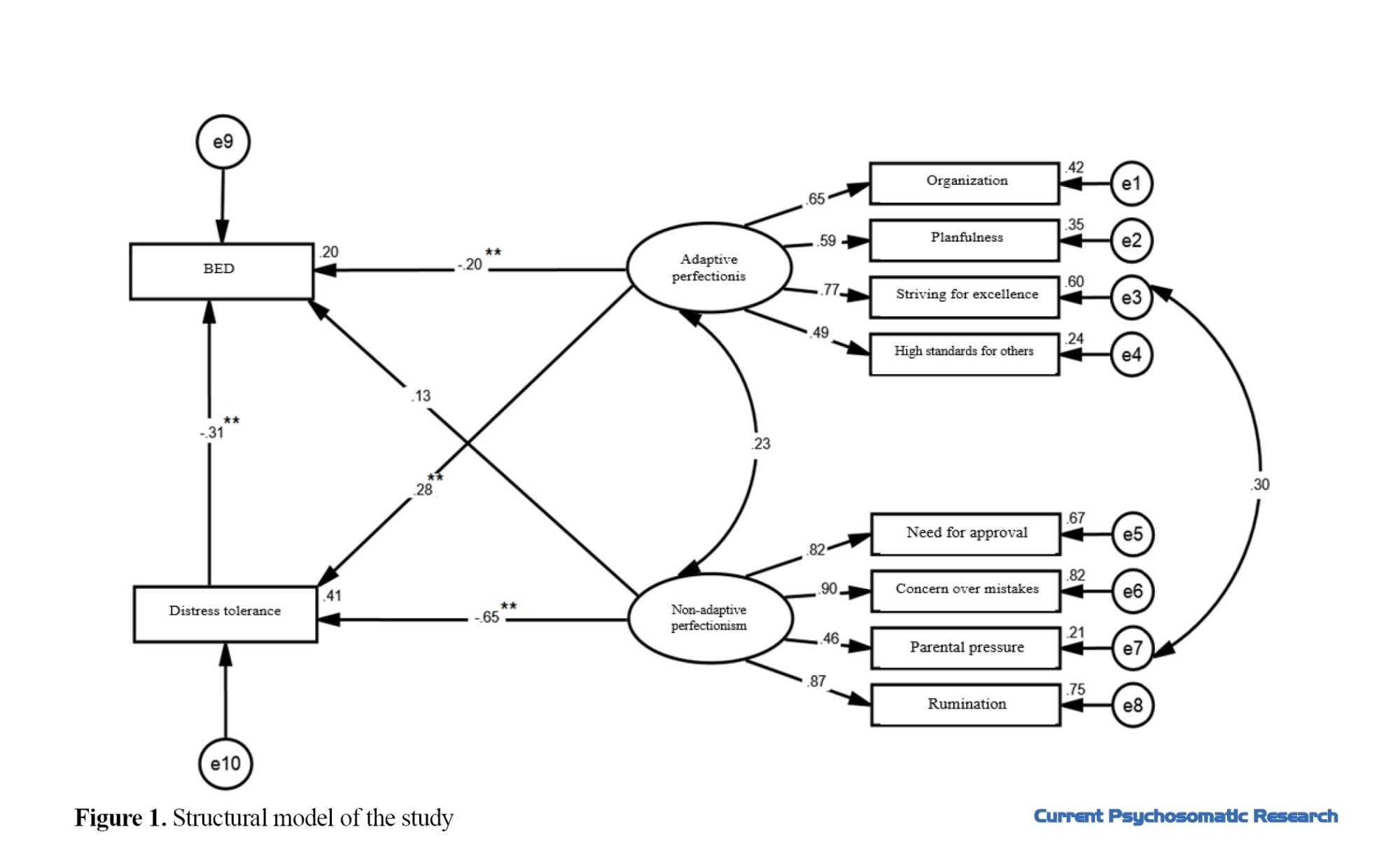

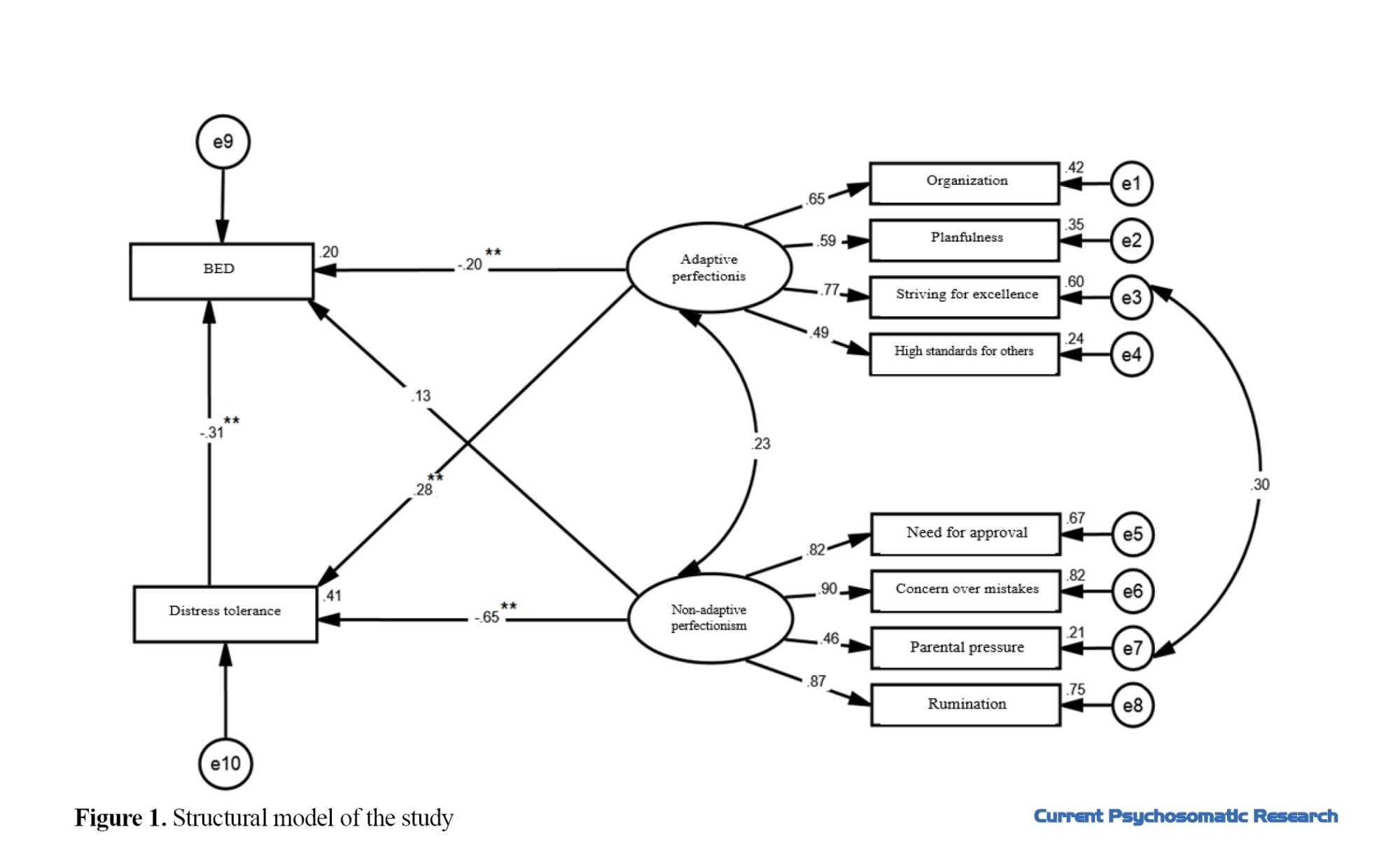

The effect coefficient between distress tolerance and BED was negative and significant (P<0.01, β=-0.314). The total effect coefficient (sum of direct and indirect path coefficients) between adaptive perfectionism and BED was negative and significant (P<0.01, β=-0.286), while the total path coefficient between non-adaptive perfectionism and BED was positive and significant (P<0.01, β=0.329). The indirect effect coefficient between adaptive perfectionism and BED was negative and significant (P<0.01, β=-0.086), while the indirect effect coefficient between non-adaptive perfectionism and BED was positive and significant (P<0.01, β=0.329). Therefore, it can be said that distress tolerance among female college students negatively mediates the relationship between adaptive perfectionism and BED, and positively mediates the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and BED. Figure 1 shows the structural model of the study.

Discussion

In the present study, which was conducted with the aim of investigating the relationship between perfectionism and BED mediated by distress tolerance in female college students, the results showed that distress tolerance negatively mediated the relationship between adaptive perfectionism and BED, and positively mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and BED. These results are consistent with Hassan’s findings [41], where it was also shown that high perfectionism is associated with less distress tolerance. The results of Vanzhula et al.’s [15] are also consistent with our results. They reported that maladaptive perfectionism predicts eating disorders. These findings are partly consistent with the results of Mullane [42] and partly against their results. The discrepancy can be due to the indirect relationship between distress tolerance and BED. In Mullane’s study [42], the results showed that people with less distress tolerance had high levels of depression, anxiety, and experiential avoidance, and thus they were more likely to have BED. The results of the present study are against the results of Kelly et al. [43]. They showed that distress tolerance was not related to BED. This discrepancy can be the due difference in the study samples and the BED measurement tool. The results of Migliore [16] support the results of the current study. She reported a direct relationship between perfectionism and BED, and an indirect relationship between distress intolerance and BED. Also, her results indicated that distress tolerance actually acts as a coping response that determines whether a high-risk situation such as perfectionism or overestimation of weight, shape and eating, or food restriction actually leads to an eating disorder or not. In this regard, distress tolerance plays a mediating role between perfectionism and BED. The results of Peixoto et al. [33] also support the findings of the present study regarding the direct relationship between perfectionism and BED. The results of other studies [17، 18] are also in line with our results. They showed that low distress tolerance plays an important role in the etiology and persistence of eating disorders. Tolerance and expectation of foods to reduce the negative felings predict the occurrence of eating disorders. In other words, distress tolerance plays an important role in the misinterpretation of threats. A low level of distress tolerance causes the individual to use maladaptive strategies to cope with the distress. In this regard, it can be argued that there is a relationship between different coping mechanisms and distress tolerance [17]. Vois et al.’s results [44]support the findings of the present study. They show that the desire to achieve high personal standards and rumination in perfectionists are predictors of eating disorders. The findings of other studies [45, 46] are also consistent with the results of the present study in some aspects. In these studies, it was shown that perfectionism can cause the formation of negative emotions and psychological distress. Since the main mechanism of these problems is a defect in emotion regulation, we can say that the cognitive emotion dysregulation and the ineffective emotional distress tolerance can cause the creation and continuation of negative moods and finally turn to BED.

There were some limitations or disadvantages in this study, including the use of a cross-sectional design which prevents a deep understanding of the causal relationships between variables. These relationships over time can only be examined by a longitudinal design. Also, self-report tools were used to collect information in this study. In future studies, it is recommended to use other tools such as observer reports, behavioral measures, or interviews for evaluation. It is recommended to conduct a similar study in other populations and samples and compare the results with the present study. Academic counselors can use the findings of this research in their occupational therapy.

Conclusion

Distress tolerance in female college students negatively mediates the relationship between adaptive perfectionism and BED, and positively mediates the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and BED. Distress tolerance causes distress that is mentally annoying or personally threatening (such as negative emotions, physical disturbances) to be tolerated. Possible individual differences in tolerance of these states can indicate how distressing they are to experience. When people use distress tolerance methods, they can better accept, evaluate and manage their emotions; as a result, they show less perfectionism in doing things, and this can lead to a reduction in BED.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has ethical approval from Isfahan University of Medical Sciences as a project (Code: IR.ARI.MUI.REC.1401.032).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their cooperation in this study.

Eating disorders are known as one of the common psychosomatic problems [1] that play a role in a wide range of issues related to mental health and are more prevalent among people aged 20-40 years [2]. Eating disorders are characterized by persistent disturbances in eating and related behaviors that cause changes in food consumption or absorption and are also significantly associated with damage to physical or psychological functioning [3]. According to the fifth edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5), these disorders include pica, rumination disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder (BED), and unspecified eating disorder [4]. Guerdjikova et al. [5] considered BED to be the most common eating disorder and stated that this disorder is usually neglected in both males and females, and affected people are not treated. According to the DSM-5 criteria, the lifetime prevalence of BED is 0.9%, and its 12-month prevalence is 0.4% [6]. Eating disorders are more common in females, such that in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, the ratio of female to male is 9:1, and in BED, the ratio is 6:4 [7]. Evidence showed that BED is equally common in male and female Iranian college students, although gender differences were also observed in some components [8]. Eating disorders, especially BED, is associated with unpleasant consequences such as obesity [9], depression, anxiety [10], suicide [11], and drug use [12]. There are also other variables as predictors of BED, the most important of which are the idealization of thinness and body dissatisfaction [13]. Regarding the etiology of BED, various factors including biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors have been implicated [14]. Among the psychological factors, the role of perfectionism in the formation of BED has been emphasized in some studies [15، 16]. Some studies have shown that the direct effect of perfectionism on eating disorders is not significant, but perfectionism is related to eating disorders by creating negative moods and especially depression [10]. In addition, some studies reported that distress tolerance can play a mediating role between perfectionism and eating disorders [16-18, 19]. These studies on the link between perfectionism and eating disorders are about trait perfectionism. In our study, perfectionism is studied in the form of two types: Adaptive and non-adaptive. In addition, most of these studies have been conducted in the United States or Canada, and not in Iran. Since the results of perfectionism may be influenced by socio-cultural factors, the present study was carried out in Iran. The results of some studies indicated a significant and strong relationship between perfectionism and distress tolerance [20، 21]. People with eating disorders show lower distress tolerance [18, 23-24]. The sum of these findings makes this research hypothesis that the relationship between perfectionism and eating disorders can be indirect and through other variables such as distress tolerance.

Distress tolerance is defined as a person’s ability to experience and tolerate negative emotional states. In fact, distress tolerance is an individual factor that refers to the capacity to withstand emotional distress [25]. It is considered a proxy for strengthening positive reactions in stressful situations [26]. Low levels of distress tolerance make a person vulnerable to many psychological injuries [27]. Distress tolerance appears in two forms; one form refers to a person’s ability to tolerate negative emotions, and the other is the behavioral manifestation of tolerating unpleasant internal states caused by various stressful situations [28]. People with low distress tolerance engage in disorganized behaviors in a wrong attempt to deal with their negative emotions [29]. By engaging in some harmful behaviors such as consuming drugs, alcohol, and excessive foods, they try to relieve their emotional pain, which leads to their temporary relief from negative emotions [30]. The results of studies indicated that distress tolerance is related to both perfectionism and BED [16-18، 31]. Previous studies on low distress tolerance, emotion regulation difficulties, and eating disorders have mainly conceptualized emotion dysregulation as broad problems related to the perception of emotional experiences, the use of flexible strategies, and the tolerance of negative emotions. For example, it was shown that anorexia nervosa in healthy students is associated with increased difficulties in cognitive emotion regulation, including limited access to adaptive cognitive emotion regulation skills [32]. There is limited attention to the ability to tolerate distress. Previous studies suggest frequent use of observed variables, which neglect potential measurement errors that can obscure true interactive correlations [33]. For example, inconsistent findings on the relationship between perfectionism and eating disorders can be due to random measurement errors in observed variables. These errors may have similarly influenced the true interaction effects of perfectionism and distress tolerance on eating disorders. Therefore, the need to use more accurate methods such as structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate hidden and mediating variables is evident. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the relationship between perfectionism and BED in female college students mediated by distress tolerance.

Methods

This is a descriptive-correlational study using SEM. The study population consists of all female college students in Isfahan, Iran, of whom 214 were selected as the samples. The sample size was determined using the formula proposed by Kline [34]; by considering 20 participants for each parameter, the sample size was determined 180, but given the possible sample drop and the incompleteness of some questionnaires, it was increased to 214. After explaining the study objectives to the participants and obtaining informed consent from them, they were asked to complete the perfectionism inventory (PI), distress tolerance scale (DTS), and binge eating scale (BES).

The BES was developed by Gormally et al. [35] to measure the severity of BED in obese people. It has 16 items rated on a scale from 0 to 3. The total score ranges from 0 to 46; a score of 16 indicates a BED, and a score >16 shows severe BED. The split-half reliability, test re-test reliability, and internal consistency of the Persian version of BES have been reported as 0.67, 0.72, and 0.85 [36].

The DTS was developed by Simons and Gaher [26] as a self-report tool for measuring distress tolerance. It has 15 items and four subscales of tolerance, absorption, appraisal, and regulation. The items are rated on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to five (strongly disagree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of distress tolerance. The α coefficients for the subscales of DTS are 0.72, 0.82, 0.78, and 0.70, respectively. For the whole scale, it is 0.82. The intraclass correlation coefficient for a six-month interval was 0.61. Also, the discriminant validity of this scale by assessing its relationship with the negative and positive affect subscales of the general temperament survey [37] was reported as 0.59 and 0.26, respectively [26]. Cronbach’s α of the Persian DTS has been reported as 0.67, and its test re-test reliability is 0.79 [38] .

The PI was developed by Hill et al. [39] with 59 items to measure eight different dimensions of perfectionism including “concern over mistakes,” “high standards for others,” “need for approval,” “organization,” “parental pressure,” “planfulness,” “rumination,” and “striving for excellence.” For scoring, it uses a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The internal consistency using Cronbach’s α for the components ranges from 0.83 to 0.91 [39]. For the Persian, the α is 0.91 for the whole scale. For the components, it ranges from 0.69 to 0.85 [40]. The test re-test reliability for a one-month interval was 0.73 [40]. The construct validity was also examined using exploratory factor analysis. The results indicated a 6-factor model of the Persian PI; these 6 factors were able to predict 45% of the total variance [40].

The collected data were analyzed in AMOS software, version 22 using SEM. The mediating role of distress tolerance was measured based on Baron & Kenny’s method.

Results

Participants were 167 single female students (77.3%) and 49 married female students (22.7%) with a mean age of 23.61±4.75 years. Among the participants, 31(14.4%) were studying for an associate degree, 131(60.6%) for a bachelor’s degree, 42(19.4%) for a master’s degree, and 12(5.6%) for a PhD degree. Table 1 shows the Mean±SD of the scores and the correlation coefficients between adaptive perfectionism, maladaptive perfectionism, distress tolerance, and BED. As can be seen, among the components of adaptive perfectionism, organization and striving for excellence were negatively correlated with BED (P<0.05), while planfulness was negatively correlated (P<0.01). Among the components of non-adaptive perfectionism, the need for approval (P<0.01), concern over mistakes (P<0.01), parental pressure (P<0.05), and rumination (P<0.05) were positively correlated with BED. Distress tolerance was negatively correlated with BED (P<0.01).

To evaluate the normality of the data distribution, the skewness and kurtosis of the variables, and the assumption of collinearity, the values of variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance coefficient were measured. The results are presented in Table 2. As can be seen, the skewness and kurtosis values of all variables were in the range of ±2, indicating that the assumption of normality of data distribution is confirmed. Moreover, the tolerance coefficient values variables were greater than 0.1 and their VIF values were less than 10. Therefore, the assumption of collinearity was also confirmed. The Mahalanobis distance and the scatterplot of standardized residuals showed that the normality of multivariate data distribution and homogeneity of variances were also established.

The fit of the measurement model was evaluated using the confirmatory factor analysis method in AMOS software, version 24.

It was assumed that adaptive perfectionism is measured by indicators of organization, planfulness, striving for excellence, and high standards for others, while maladaptive perfectionism is measured by indicators of need for approval, concern on mistakes, parental pressure, and rumination. Table 3 shows the fit indices of the measurement model and the structural model. The results show the acceptable fit of the measurement model (primary and modified) to the collected data. Due to the importance of the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) index, the measurement model was modified by creating a covariance between the errors of the indicators of striving for excellence and parental pressure.

Table 4 shows the standardized and unstandardized factor loadings, standardized error, and critical ratio. As can be seem, the highest factor load belonged to the indicator of concern over mistakes (β=0.918) while the lowest factor load belonged to the indicator high standards for others (β=0.459). Considering that the factor loadings of all indicators were higher than 0.32, it can be said that all indicators had the necessary power to measure the latent variables. In the structural model of the study, it was assumed that adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism predicts BED directly and through the emotional distress tolerance. The results in Table 4 showed that the acceptable fit of the structural model to the collected data.

The effect coefficient between distress tolerance and BED was negative and significant (P<0.01, β=-0.314). The total effect coefficient (sum of direct and indirect path coefficients) between adaptive perfectionism and BED was negative and significant (P<0.01, β=-0.286), while the total path coefficient between non-adaptive perfectionism and BED was positive and significant (P<0.01, β=0.329). The indirect effect coefficient between adaptive perfectionism and BED was negative and significant (P<0.01, β=-0.086), while the indirect effect coefficient between non-adaptive perfectionism and BED was positive and significant (P<0.01, β=0.329). Therefore, it can be said that distress tolerance among female college students negatively mediates the relationship between adaptive perfectionism and BED, and positively mediates the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and BED. Figure 1 shows the structural model of the study.

Discussion

In the present study, which was conducted with the aim of investigating the relationship between perfectionism and BED mediated by distress tolerance in female college students, the results showed that distress tolerance negatively mediated the relationship between adaptive perfectionism and BED, and positively mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and BED. These results are consistent with Hassan’s findings [41], where it was also shown that high perfectionism is associated with less distress tolerance. The results of Vanzhula et al.’s [15] are also consistent with our results. They reported that maladaptive perfectionism predicts eating disorders. These findings are partly consistent with the results of Mullane [42] and partly against their results. The discrepancy can be due to the indirect relationship between distress tolerance and BED. In Mullane’s study [42], the results showed that people with less distress tolerance had high levels of depression, anxiety, and experiential avoidance, and thus they were more likely to have BED. The results of the present study are against the results of Kelly et al. [43]. They showed that distress tolerance was not related to BED. This discrepancy can be the due difference in the study samples and the BED measurement tool. The results of Migliore [16] support the results of the current study. She reported a direct relationship between perfectionism and BED, and an indirect relationship between distress intolerance and BED. Also, her results indicated that distress tolerance actually acts as a coping response that determines whether a high-risk situation such as perfectionism or overestimation of weight, shape and eating, or food restriction actually leads to an eating disorder or not. In this regard, distress tolerance plays a mediating role between perfectionism and BED. The results of Peixoto et al. [33] also support the findings of the present study regarding the direct relationship between perfectionism and BED. The results of other studies [17، 18] are also in line with our results. They showed that low distress tolerance plays an important role in the etiology and persistence of eating disorders. Tolerance and expectation of foods to reduce the negative felings predict the occurrence of eating disorders. In other words, distress tolerance plays an important role in the misinterpretation of threats. A low level of distress tolerance causes the individual to use maladaptive strategies to cope with the distress. In this regard, it can be argued that there is a relationship between different coping mechanisms and distress tolerance [17]. Vois et al.’s results [44]support the findings of the present study. They show that the desire to achieve high personal standards and rumination in perfectionists are predictors of eating disorders. The findings of other studies [45, 46] are also consistent with the results of the present study in some aspects. In these studies, it was shown that perfectionism can cause the formation of negative emotions and psychological distress. Since the main mechanism of these problems is a defect in emotion regulation, we can say that the cognitive emotion dysregulation and the ineffective emotional distress tolerance can cause the creation and continuation of negative moods and finally turn to BED.

There were some limitations or disadvantages in this study, including the use of a cross-sectional design which prevents a deep understanding of the causal relationships between variables. These relationships over time can only be examined by a longitudinal design. Also, self-report tools were used to collect information in this study. In future studies, it is recommended to use other tools such as observer reports, behavioral measures, or interviews for evaluation. It is recommended to conduct a similar study in other populations and samples and compare the results with the present study. Academic counselors can use the findings of this research in their occupational therapy.

Conclusion

Distress tolerance in female college students negatively mediates the relationship between adaptive perfectionism and BED, and positively mediates the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and BED. Distress tolerance causes distress that is mentally annoying or personally threatening (such as negative emotions, physical disturbances) to be tolerated. Possible individual differences in tolerance of these states can indicate how distressing they are to experience. When people use distress tolerance methods, they can better accept, evaluate and manage their emotions; as a result, they show less perfectionism in doing things, and this can lead to a reduction in BED.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has ethical approval from Isfahan University of Medical Sciences as a project (Code: IR.ARI.MUI.REC.1401.032).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Mason TB, Mozdzierz P, Wang S, Smith KE. Discrimination and eating disorder psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 2021; 52(2):406-17. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2020.05.003] [PMID]

- Rehm J, Shield KD. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019; 21(2):10. [DOI:10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0] [PMID]

- Joyce-Beaulieu D, Sulkowski ML. The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: (DSM-5) model of impairment. Assessing impairment. In: Goldstein S, Naglieri J, editors. Assessing impairment. Boston: Springer; 2016. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4899-7996-4_8]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

- Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Casuto LS, McElroy SL. Update on binge eating disorder. Med Clin North Am. 2019; 103(4):669-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.mcna.2019.02.003] [PMID]

- Udo T, Grilo CM. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of U. S. adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2018; 84(5):345-54. [PMID]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007; 61(3):348-58. [PMID]

- Sahlan RN, Taravatrooy F, Quick V, Mond JM. Eating-disordered behavior among male and female college students in Iran. Eat Behav. 2020; 37:101378. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101378] [PMID]

- Stice E, Desjardins CD, Shaw H, Rohde P. Moderators of two dual eating disorder and obesity prevention programs. Behav Res Ther. 2019; 118:77-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2019.04.002] [PMID]

- Drieberg H, McEvoy PM, Hoiles KJ, Shu CY, Egan SJ. An examination of direct, indirect and reciprocal relationships between perfectionism, eating disorder symptoms, anxiety, and depression in children and adolescents with eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2019; 32:53-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.12.002] [PMID]

- Cliffe C, Shetty H, Himmerich H, Schmidt U, Stewart R, Dutta R. Suicide attempts requiring hospitalization in patients with eating disorders: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Eat Disord. 2020; 53(5):728-35. [Link]

- Bahji A, Mazhar MN, Hudson CC, Nadkarni P, MacNeil BA, Hawken E. Prevalence of substance use disorder comorbidity among individuals with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019; 273:58-66. [PMID]

- Stice E, Johnson S, Turgon R. Eating disorder prevention. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2019; 42(2):309-18. [DOI:10.1016/j.psc.2019.01.012] [PMID]

- Bakalar JL, Shank LM, Vannucci A, Radin RM, Tanofsky-Kraff M. Recent advances in developmental and risk factor research on eating disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015; 17(6):42. [DOI:10.1007/s11920-015-0585-x] [PMID]

- Vanzhula IA, Kinkel-Ram SS, Levinson CA. Perfectionism and difficulty controlling thoughts bridge eating disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms: A network analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021; 283:302-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.083] [PMID]

- Migliore DA. Predictors of binge eating: Perfectionism, distress tolerance and eating self-efficacy [PhD dissertation]. New Jersey: The State University of New Jersey; 2010. [Link]

- Ay R, Aytas O. The relationship between eating attitudes and distress tolerance in obsessive compulsive disorder. Arch Clin Psychiatr. 2018; 45(6):139-42. [DOI:10.1590/0101-60830000000176]

- Hovrud L, Simons R, Simons J. Cognitive schemas and eating disorder risk: The role of distress tolerance. Int J Cogn Ther. 2020; 13(1):54-66. [DOI:10.1007/s41811-019-00055-5]

- Rand-Giovannetti D, Rozzell KN, Latner J. The role of positive self-compassion, distress tolerance, and social problem-solving in the relationship between perfectionism and disordered eating among racially and ethnically diverse college students. Eat Behav. 2022; 44:101598. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2022.101598] [PMID]

- Migliore DA, Napierkowski DB. A multidimensional study of the correlation between perfectionism, self-efficacy, distress tolerance and binge eating. SOJ Nur Health Care. 2020; 6(1):1-6. [Link]

- Welch K, Brott KH, Veilleux JC. Hovering or invalidating? Examining nuances in the associations between controlling parents and problematic outcomes for college students. J Am Coll Health. 2023; 1-13. [DOI:10.1080/07448481.2023.2209197] [PMID]

- Yiu A, Christensen K, Arlt JM, Chen EY. Distress tolerance across self-report, behavioral and psychophysiological domains in women with eating disorders, and healthy controls. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2018; 61:24-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.05.006] [PMID]

- Lavender JM, Happel K, Anestis MD, Tull MT, Gratz KL. The interactive role of distress tolerance and eating expectancies in bulimic symptoms among substance abusers. Eat Behav. 2015; 16:88-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.10.006] [PMID]

- Corstorphine E, Mountford V, Tomlinson S, Waller G, Meyer C. Distress tolerance in the eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2007; 8(1):91-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.02.003] [PMID]

- O’Cleirigh C, Ironson G, Smits JAJ. Does distress tolerance moderate the impact of major life events on psychosocial variables and behaviors important in the management of HIV? Behav Ther. 2007; 38(3):314-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2006.11.001] [PMID]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and Validation of a self-report measure. Motiv Emot. 2005; 29(2):83-102. [DOI:10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3]

- Saleem S, Renshaw KD, Azhar M, Giff ST, Mahmood Z. Interactive effects of perceived parental rearing styles on distress tolerance and psychological distress in Pakistani University students. J Adult Dev. 2021; 28(4):309-18. [DOI:10.1007/s10804-021-09373-5]

- Webb MK, Simons JS, Simons RM. Affect and drinking behavior: Moderating effects of involuntary attention to emotion and distress tolerance. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020; 28(5):576-88. [DOI:10.1037/pha0000329] [PMID]

- Keough ME, Riccardi CJ, Timpano KR, Mitchell MA, Schmidt NB. Anxiety symptomatology: The association with distress tolerance and anxiety sensitivity. Behav Ther. 2010; 41(4):567-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.002] [PMID]

- Lazarus RS. Cognition and motivation in emotion. Am Psychol. 1991; 46(4):352-67. [DOI:10.1037//0003-066x.46.4.352] [PMID]

- Brosof LC, Egbert AH, Reilly EE, Wonderlich JA, Karam A, Vanzhula I, et al. Intolerance of uncertainty moderates the relationship between high personal standards but not evaluative concerns perfectionism and eating disorder symptoms cross-sectionally and prospectively. Eat Behav. 2019; 35:101340. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.101340] [PMID]

- Haynos AF, Wang SB, Fruzzetti AE. Restrictive eating is associated with emotion regulation difficulties in a non-clinical sample. Eat Disord. 2018; 26(1):5-12. [DOI:10.1080/10640266.2018.1418264] [PMID]

- Peixoto-Plácido C, Soares MJ, Pereira AT, Macedo A. Perfectionism and disordered eating in overweight woman. Eat Behav. 2015; 18:76-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.03.009] [PMID]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Publications; 2023. [Link]

- Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav. 1982; 7(1):47-55. [DOI:10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7] [PMID]

- Mouloudi R, Dezhkam M, Moutabi F, Omidvar N. [Comparison of early maladaptive schema in obese binge eaters and obese non-binge eaters (Persian)]. J Behav Sci. 2010; 4(2):109-14. [Link]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991; 100(3):316-36. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316] [PMID]

- Azizi A, Mirzaei A, Shams J. [Correlation between distress tolerance and emotional regulation with students smoking dependence (Persian)]. Hakim 2010; 13(1):11-8. [Link]

- Hill RW, Huelsman TJ, Furr RM, Kibler J, Vicente BB, Kennedy C. A new measure of perfectionism: The perfectionism inventory. J Pers Assess. 2004; 82(1):80-91. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa8201_13] [PMID]

- Samaei S, Hooman HA, Tavakoli MH, Bagherian F. An investigation of psychometric properties of perfectionism inventory in Iranian Sample. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015; 205:556-63. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.075]

- Hassan S. Perfectionism and distress tolerance as psychological vulnerabilities to traumatic impact and psychological distress in persons with psychotic illness[PhD dissertation]. Toronto: York University; 2017. [Link]

- Mullane CN. Distress tolerance, experiential avoidance, and negative affect: Implications for understanding eating behavior and BMI [PhD dissertation]. Knoxville: University of Tennessee; 2011. [Link]

- Kelly NR, Cotter EW, Mazzeo SE. Examining the role of distress tolerance and negative urgency in binge eating behavior among women. Eat Behav. 2014; 15(3):483-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.06.012] [PMID]

- Vois D, Damian LE. Perfectionism and emotion regulation in adolescents: A two-wave longitudinal study. Pers Individ Dif. 2020; 156:109756. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109756]

- Christian C, Martel MM, Levinson CA. Emotion regulation difficulties, but not negative urgency, are associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and eating disorder symptoms in undergraduate students. Eat Behav. 2020; 36:101344.[DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.101344] [PMID]

- Tng GY, Yang H. Interactional effects of multidimensional perfectionism and cognitive emotion regulation strategies on eating disorder symptoms in female college students. Brain Sci. 2021; 11(11):1374. [DOI:10.3390/brainsci11111374] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2023/01/21 | Accepted: 2023/05/31 | Published: 2023/07/1

Received: 2023/01/21 | Accepted: 2023/05/31 | Published: 2023/07/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |