Wed, Nov 19, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 2, Issue 4 (Summer 2024)

CPR 2024, 2(4): 277-286 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Tousheh F, Firoozi A, Gelehkolaee K S, Nikbakht R, Khani S. The Effect of Midwife-led Integrative Couple Counseling on Sexual Desire Discrepancy in Postpartum Couples: A Study Protocol for a RCT. CPR 2024; 2 (4) :277-286

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-145-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-145-en.html

Student Research Committee, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

Keywords: Sexual desire discrepancy, integrated counseling, couple therapy, sexual satisfaction, postpartum, sexual dysfunction

Full-Text [PDF 888 kb]

(46 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (370 Views)

Equipment

Data collection tools

The data collection instruments in this study include a demographic information form, the HISD, the depression anxiety stress scales-21 (DASS-21), and the index of sexual satisfaction (ISS) by Hudson. Before the intervention begins, the links to the questionnaires on Porsline will be provided to the couples. Immediately after the counseling sessions end, a post-test and a follow-up session will be conducted four weeks [24] and three month [25] later to reassess and compare the two groups in terms of SDD and sexual satisfaction.

The demographic questionnaire consists of four sections: Socio-demographic characteristics, pregnancy and childbirth history, sexual history, and medical history. The content validity of this form will be confirmed by a panel of experts from Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, specializing in midwifery, reproductive health, and psychology.

Primary outcome measures

SDD: In this study, SDD will be assessed through two approaches: At the individual level and at the couple/group level.

At the individual level, participants will respond to a single-item question: “Do you feel that you and your partner are at almost the same level of sexual desire?”.

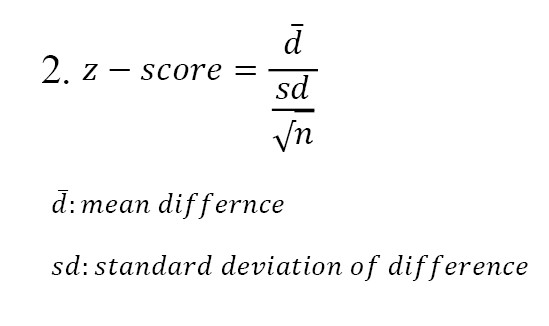

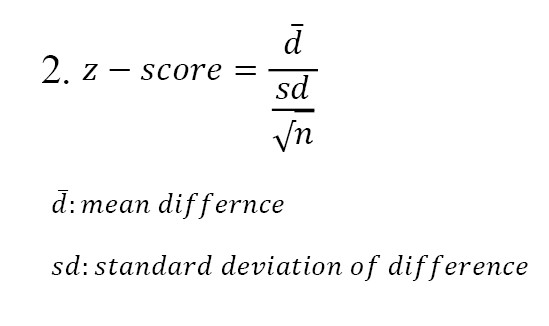

At the couple and group level, desire discrepancy will be calculated using the HISD by measuring the standardized difference between partners’ sexual desire scores. To assess whether there is a meaningful difference between women’s and their husbands’ levels of sexual desire, the Z-score test is used. Specifically, the Z-score of the male partner will be subtracted from the Z-score of the female partner (Z-woman–Z-man). If the absolute value of the Z-score exceeds 1.96 (at a 95% confidence level [CI]), we can conclude that the difference in sexual desire between the couple is statistically significant. On the other hand, if the Z-score falls between -1.96 and +1.96, it indicates that the difference is not statistically significant (Equation 2) [10, 26].

The HISD, developed by Apt and Halbert, has demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability [27]. In a study conducted by Ahmadnia et al. (2020), the content and face validity of the instrument were confirmed, and internal consistency was verified with a Cronbach’s α of 0.87 [28].

Secondary outcome measures

Sexual satisfaction: Sexual satisfaction will be evaluated using the Hudson sexual satisfaction questionnaire, developed by Hudson et al. in 1981. This instrument consists of 25 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, assessing various aspects of sexual satisfaction [29]. The original version of the questionnaire was designed to measure marital satisfaction in 70 couples and has demonstrated acceptable validity [29]. In a study conducted by Shams Mofaraheh at Iran University of Medical Sciences, the Persian version of the Hudson sexual satisfaction questionnaire was standardized and shown to have strong psychometric properties. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α, which yielded values of 0.93 for the fertile group and 0.89 for the infertile group [30].

To assess participants’ levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, the DASS-21 will be utilized. This scale was originally developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) and further analyzed by Antony et al. who confirmed the three-factor structure, depression, anxiety, and stress. The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) for these subscales was reported as 0.97, 0.92, and 0.95, respectively [31]. In Iran, Asghari et al. validated the Persian version of the DASS-21, confirming its reliability and construct validity. The reliability coefficient for the total scale was reported as r=0.91 [32].

Data management

Participants will be assured that all data will be collected and handled in accordance with strict confidentiality principles. Data will be collected anonymously and encoded to protect participants’ identities. Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. To respect participants’ autonomy, they will be informed that participation is voluntary, and that they may withdraw from the study at any time without any impact on their access to medical or health services. Additionally, to ensure privacy and comfort, all counseling sessions will be held in a private and soundproof setting.

Interventions

After selecting eligible participants, access links to the demographic questionnaire, the DASS-21, and the HISD will be provided to the couples. Participants who score in the severe to extremely severe range for depression, anxiety, or stress in the DASS-21 will be excluded from the study and referred to a psychiatrist. As mentioned, SDD in couples will be assessed in two ways: At the individual level and at the couple/group level. At the individual level (which, in fact, serves as the inclusion criterion for identifying SDD), discrepancy will be measured using a single question: “Do you feel that you and your partner are at almost the same level of sexual desire?” Possible answers will be yes (0) and no (1). Individuals who do not report a discrepancy at the individual level will not be included in the study. At the couple/group level (after the completion of sampling and after all couples have responded to the questionnaire, the quantitative and statistical calculation of SDD between couples will be conducted), desire discrepancy will be calculated using scores from the Halbert sexual desire index. The difference between standardized scores (Z-scores) of each couple will be used—specifically, the man’s Z-score will be subtracted from the woman’s Z-score [10]. Positive scores indicate that the woman has a higher level of desire than her male partner; negative scores indicate the opposite. A Z-score with a 95% CI>1.96 will be considered significant. Finally, 32 couples will be enrolled in the study after providing informed consent. Participants will be randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group using blocked randomization, with 16 couples in each group. The couple counseling sessions will last approximately 60 minutes [33] and take place over five sessions (6 weeks). In addition, the sessions will be conducted remotely through secure video conferencing (e.g. Google Meet or WhatsApp) to ensure accessibility and convenience [34]. The counseling sessions are conducted by a master’s student in midwifery counseling. prior to initiating the interventions, she has participated in specialized workshops on sexual health, treatment of sexual dysfunctions, and couples counseling, and holds valid certifications in these areas. Participants will be contacted once or twice per week to ensure homework completion. The homeworks given to the couples will consist of the same educational content provided during each session. They will be asked to regularly practice these skills throughout the week in order to enhance intimacy and improve their relationship interactions. In the first session, before the intervention begins, the Hudson sexual satisfaction questionnaire will be administered to both partners to allow for comparison of pre- and post-intervention scores. Post-tests will be administered immediately after the final session, and a follow-up session will take place four weeks [24] and three month [25] later to reassess SDD and sexual satisfaction in both groups.

Midwife-led integrative couple counseling

In the intervention group, integrative couple counseling will be conducted by a trained researcher who has completed certified training in couples counseling and the treatment of sexual disorders. Each couple in the intervention group will participate in five 60-minute sessions of integrative couple counseling (Table 2).

Control group

The control group will receive routine care, including standard midwifery care and treatments following delivery (such as performing papsmear, treating vaginal infections, managing potential anemia and so on). The same questionnaires will be administered at all stages concurrently with the intervention group.

Protocol deviation

Deviations or violations of the study protocol may occur and will be documented and reported. In cases where participants are excluded from the study for any reason, the reasons for withdrawal will be recorded. The data from these participants will be analyzed using the intention-to-treat (ITT) approach.

Modification to the protocol

Any changes in procedure that may affect the study’s conduct, the patient’s potential benefits, or the patient’s safety, including changes in study objectives, study design, patient population, sample size, the study method or important administrative aspects will require the official documents of this amendment with the approval of the research team and the approval of the ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

The data will be collected individually from participants in both the intervention and control groups, and the difference in sexual desire will be calculated for each. Since sexual desire is measured at four different time points (pre-intervention, five weeks after the start of the intervention, four weeks and three month post-intervention), various statistical tests will be used depending on whether the normality assumption is met (tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test): The normality of quantitative data will be assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests, and equality of variances will be examined using Levene’s test and the F-test. If the data meet normality assumptions: an independent samples t-test will be used for between-group comparisons, a paired t-test will assess within-group changes, repeated measures ANOVA will evaluate changes over time between the two groups. A mixed-effects model will also be applied to account for within-subject correlations and to control for potential confounding variables. If the normality assumption is not met: Non-parametric tests such as the Mann–Whitney U test (between-group), the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (within-group), and the Friedman test (for repeated measures) will be employed. Additionally, the generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach will be used for analyzing repeated measures data in a non-parametric framework. The effect size and its 95% CI will be calculated for each outcome to determine the clinical significance of findings. A significance level of 0.05 will be considered for all statistical analyses. Data analysis will be conducted using SPSS software, version 22.

Discussion

The current study aims to determine the effectiveness of five-session integrative couple counseling for couples after their delivery with SDD. Couples generally experience a significant decrease in postpartum sexual activity due to hormonal changes and adherence to the role of parents [35]. Changes in the roles and responsibilities of partners as new parents, lack of private time as a couple, increased stress, and fatigue have been suggested as explanations for decreased desire and sexual activity after the birth of the baby [36, 37]. The high incidence of SDD [2, 9], coupled with its potential to exacerbate relational conflicts [2] and diminish overall relationship satisfaction [10, 12], emphasizes the need for targeted interventions. Vowels et al. aim to “effect an online sex therapy program without a therapist on the treatment of couples’ SDD. “ A case study of 10 people found that using couple strategies and treatments instead of focusing on the individual helped improve and treat [4].

Current results show that SDD is significantly associated with sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction [4, 10-12]. Kleinplatz et al. conducted a group therapy intervention to improve sexual satisfaction in 14 couples with low sexual desire or SDD, which was associated with increasing sexual satisfaction and satisfaction with the intensity of sexual arousal, variety, and frequency of sex [38]. Zamani et al. conducted a clinical trial on 75 postpartum women with low sexual satisfaction who received four sexual counseling sessions based on the womens postpartum sexual health program (WPSHP), including three group sessions and one couple counseling session. They showed a significant improvement in sexual satisfaction scores in the intervention group [19]. Aghababaei et al. conducted a clinical trial study to determine the effectiveness of sexual health counseling on the sexual function of 104 lactating women with low sexual desire. Weekly sessions for 4 weeks were based on the rapport building, exploration, decision making, and implementing the decision (REDI) model, which was associated with an increase in female sexual function index (FSFI) in the intervention group [39]. Our study is based on the results of studies that highlight the prevalence and distress associated with postpartum SDD [9].

In order to design the intervention in the present study, an integrative couples counseling approach was used, which has evidence of its effectiveness in improving sexual disorders in previous studies. A study by Samadi et al. was designed and implemented as a randomized clinical trial with 24 couples suffering from hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). Participants were randomly assigned to two groups: Intervention and control. The intervention group received integrative couples counseling treatment, which consisted of 10 sessions, once a week, for 90 minutes. The instruments used in this study included the HISD, FSFI and international index of erectile function (IIEF), which was administered at pre-test, post-test, and eight-week follow-up. The results showed that couples in the intervention group, especially women, experienced a significant increase in sexual desire, and this improvement was maintained at the follow-up stage [40]. In a study conducted by Nezamalmolki et al., 30 women experiencing marital infidelity underwent 9 sessions of 90-minute integrative couples counseling in a quasi-experimental design (pre-test–post-test–3-month follow-up). These interventions included cognitive-behavioral techniques, emotion regulation, and programs to promote marital intimacy and sexual health. The results of this study showed that therapists were able to significantly increase sexual functioning and marital intimacy and reduce impulsivity; and these positive changes were sustained up to three months after the end of treatment [41]. The effectiveness of couple strategies, such as increasing communication and sexual intimacy, over individual strategies [4] supports the rationale for our focus on midwife-led integrative couple counseling. Integrative couple counseling, with emphasis on circular causality and the collaborative nature of change, offers a promising approach to mitigating SDD [13]. The lack of clinical studies on this topic in Iran highlights the need for more local studies to ensure the applicability and relevance of integrative couples counseling in different cultural and social contexts. Also, our study highlights a gap in studies related to the use of midwife-led integrative couple counseling, specifically in the Iranian context. Based on the emphasis of The WHO on providing sexual information and counseling to women based on their needs in maternal and newborn care [15] and considering the positive effects of midwife-led couple counseling on addressing sexual satisfaction issues in different populations [16-18] and improving sexual satisfaction and sexual desire in women with sexual disorders after childbirth [19], it seems that the intervention of a midwife can be effective in this field.

This study protocol is subject to some limitations, such as restricted access to eligible participants and the impossibility of participant blinding due to the characteristics of the intervention, which may introduce potential bias.

Also, if the intervention shows promising results, the protocol may be shared with health policymakers and planners to support the potential integration of this approach into sexual health counseling and the management of SDD within primary health care (PHC) services.

Conclusion

Considering the negative consequences of SDD on the quality of couples’ relationships, including weakening emotional bonds, exacerbating marital conflicts, and increasing the psychological and emotional distance between couples, it can be said that this phenomenon not only challenges relationship stability, but also leads to reduced effective interactions, decreased sexual satisfaction, and ultimately decreased overall relationship satisfaction. Since the postpartum period is a critical and sensitive period in the common life of couples, and psychological, physiological, and new roles can affect couples’ relationships, the design and implementation of interventions aimed at reducing SDD and improving marital interactions during this period are of particular importance. The intervention in this study, focusing on promoting effective communication, mutual understanding, and setting sexual expectations in a healthy and supportive relationship, can play an effective role in reducing the negative effects of sexual desire differences and take steps to improve the sexual health and satisfaction of couples after delivery.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1403.304) and has been prospectively registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (Code: IRCT20161126031117N17). All ethical guidelines and codes of conduct will be strictly observed throughout the research process. All ethical principles regarding participants’ rights will be strictly upheld in this study. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants, and the confidentiality of their personal information will be fully guaranteed throughout the intervention.

Funding

This project was financially supported by the Student Research Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Investigation: Fatemeh Tousheh and Soghra Khani; Data collection: Armin Firoozi and Keshvar Samadaee Gelehkolaee and Fatemeh Tousheh; Writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Center and the Research and Technology Vice-Chancellor of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for approving the protocol, and after the completion of the study, the participants in the study are thanked.

References

Full-Text: (12 Views)

Introduction

Sexual desire/arousal disorder is the most prevalent sexual disorder occurring within the first two, four, and 6 months postpartum, affecting up to 40% of new mothers [1]. While low sexual desire is common in this period, discrepancies in sexual desire are often more distressing due to their negative impact on romantic relationships [2]. Sexual desire discrepancy (SDD) was first defined by Zilbergeld and Ellison [3] to describe when two partners in an intimate relationship exhibit different levels or frequencies of sexual activity. SDD occurs when partners’ sexual desires or preferences diverge [4] and Problems related to it is one of the most common complaints among people seeking help in treatment [5-8]. Various factors, including relationship dynamics, hormonal changes, medical conditions, and psychosocial stressors, contribute to SDD [9]. In the study by Rosen et al. on 255 couples who had just given birth, it was found that 5% of their desire levels were matched entirely (12 couples), 25% of mothers were more willing than fathers (64 couples), and 70% had fathers who were more willing than mothers (170 couples) [9]. This discrepancy may aggravate relational conflicts, diminish stability and communication, and increase discord [2]. Research has found a significant correlation between SDD and both sexual and relationship satisfaction [4, 9-12]. Despite its prevalence, limited studies have examined interventions to address SDD in couples. Vowels et al. found that couple-oriented strategies—such as enhancing communication, quality time, and sexual intimacy—were more effective predictors of satisfaction compared to individual strategies (e.g. masturbation) [7]. Regardless of the treatment path, SDD should be treated within the framework of the relationship and the couple [2, 4, 7]. A prominent approach in couples counseling and therapy is integrative couple counseling, which underscores the principle of circular causality, eschewing the attribution of blame to any single partner and instead concentrating on the couple as a collaborative unit. This model presents five stages for couples therapy: Assessment, targeting, design of specialized interventions, continuity and validation. To make changes in the couple, the behavior and feelings of both partners should be examined [13].

Women frequently encounter sexual problems after childbirth, which are typically left unreported. Consequently, they do not receive any medical intervention, a situation attributable to inadequate verbal communication between healthcare providers and mothers regarding sexual problems [14]. Therefore, during this transitional period, it is crucial for women to receive psychological counseling, highlighting the importance of midwives and healthcare professionals addressing this vital issue [1]. World Health Organization (WHO) has always emphasized that in maternal and newborn care, providing sexual information and counseling to women based on their needs is an ideal opportunity to address problems related to sexual health and sexual function [15]. Midwife-led couple counseling has demonstrated beneficial outcomes in addressing issues of sexual satisfaction across diverse populations [16-18]. It has proven effective in improving sexual satisfaction and desire among women experiencing postpartum sexual dysfunction [19].

Our extensive search in available databases has revealed a significant gap in research. To our knowledge, no randomized controlled trial study has been conducted on the effect of midwife-led integrative couple counseling on SDD in postpartum couples, either in Iran or internationally. This study, therefore, represents a novel and important contribution to the field of sexual health and postpartum care.

Materials and Methods

Aim

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the effect of midwife-led integrative couple counseling on SDD in couples after childbirth. The specific aim is to assess and compare the level of SDD between the intervention and control groups at three time points: before the intervention, immediately after, and four weeks post-intervention.

Study design

This study is a randomized clinical trial with two parallel arms: An intervention group and a control group.

Setting of the study

The participants in this study will be couples who have recently given birth and are attending health centers or urban family physician clinics in Sari, Iran.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria are as follows: written informed consent from both partners; women of childbearing age (aged 18 to 54) ; a minimum of 10 weeks postpartum [20-22]; cohabitation with a spouse; access to a smartphone (for completing forms and questionnaires); availability for the duration of the study; absence of chronic physical illnesses; no history of substance abuse; not currently pregnant; no diagnosed psychological disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety, or stress based on the DASS-21); no physical conditions interfering with sexual function; no use of psychiatric medications; no participation in educational or counseling programs related to sexual functioning in the past six months; and no history of genital or pelvic surgeries (e.g. hysterectomy) that could impact sexual desire.

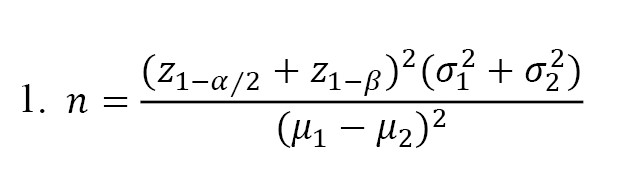

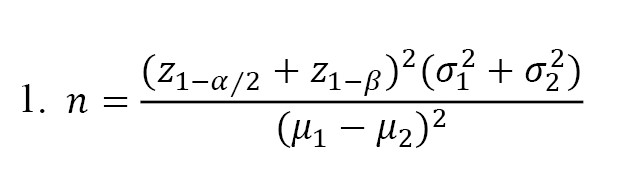

Sample size and sampling method

Based on the study by Mintz et al. [23], the Mean±SD of sexual desire scores (measured using the Hulbert index of sexual desire [HISD]) was reported as 52.44±13.20 in the intervention group and 37.01±12.74 in the control group. Using these values, and assuming a significance level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.8, the required sample size was calculated to be 12 participants. Considering an estimated 35% attrition rate, the final sample size was adjusted to 16 participants, with 16 couples in the intervention group and 16 couples in the control group (Equation 1).

Sampling will be conducted using a convenience sampling approach. After receiving approval from the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, the researcher will register the trial on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), obtain an official letter of introduction, and proceed to visit health centers and urban family physician clinics in Sari, Iran. At these centers, eligible participants will be identified based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria through the local PARSA health database. Those meeting the criteria and expressing interest in the study will be invited to participate. A list of eligible and willing participants will be compiled, and their information will be coded in an Excel spreadsheet using identification codes instead of personal identifiers. The time schedule for conducting each parts of the study is presented in Table 1.

Random allocation

In this study, participants will be matched based on the duration of marriage, number of deliveries (parity), breastfeeding status and age. Random allocation into intervention and control groups will be performed using a block randomization method. Two-couple blocks will be used, with the possible arrangements being “TC” and “CT,” where “T” represents the intervention group and “C” the control group. Block assignment will be determined using the RANDBETWEEN function in Excel, generating random numbers between 1 and 2. A value of 1 will correspond to the “CT” block, and a value of 2 to the “TC” block. Based on the generated sequence, participants will be randomly assigned to the respective groups.

Blinding

Given the nature of the intervention, participant blinding in the intervention group is not feasible. Therefore, blinding will be implemented at the outcome assessor and data analyst (statistician) levels. To ensure blinding, after the intervention sessions are completed, a research assistant will distribute the questionnaires to the participants. Once completed, the participants will place their questionnaires into a sealed box, with the groups labeled as “A” and “B” to conceal group identity. Additionally, all collected data will be anonymized and sent to the statistician using coded identifiers for analysis. The study procedure is illustrated in the CONSORT flowchart (Figure 1).

Sexual desire/arousal disorder is the most prevalent sexual disorder occurring within the first two, four, and 6 months postpartum, affecting up to 40% of new mothers [1]. While low sexual desire is common in this period, discrepancies in sexual desire are often more distressing due to their negative impact on romantic relationships [2]. Sexual desire discrepancy (SDD) was first defined by Zilbergeld and Ellison [3] to describe when two partners in an intimate relationship exhibit different levels or frequencies of sexual activity. SDD occurs when partners’ sexual desires or preferences diverge [4] and Problems related to it is one of the most common complaints among people seeking help in treatment [5-8]. Various factors, including relationship dynamics, hormonal changes, medical conditions, and psychosocial stressors, contribute to SDD [9]. In the study by Rosen et al. on 255 couples who had just given birth, it was found that 5% of their desire levels were matched entirely (12 couples), 25% of mothers were more willing than fathers (64 couples), and 70% had fathers who were more willing than mothers (170 couples) [9]. This discrepancy may aggravate relational conflicts, diminish stability and communication, and increase discord [2]. Research has found a significant correlation between SDD and both sexual and relationship satisfaction [4, 9-12]. Despite its prevalence, limited studies have examined interventions to address SDD in couples. Vowels et al. found that couple-oriented strategies—such as enhancing communication, quality time, and sexual intimacy—were more effective predictors of satisfaction compared to individual strategies (e.g. masturbation) [7]. Regardless of the treatment path, SDD should be treated within the framework of the relationship and the couple [2, 4, 7]. A prominent approach in couples counseling and therapy is integrative couple counseling, which underscores the principle of circular causality, eschewing the attribution of blame to any single partner and instead concentrating on the couple as a collaborative unit. This model presents five stages for couples therapy: Assessment, targeting, design of specialized interventions, continuity and validation. To make changes in the couple, the behavior and feelings of both partners should be examined [13].

Women frequently encounter sexual problems after childbirth, which are typically left unreported. Consequently, they do not receive any medical intervention, a situation attributable to inadequate verbal communication between healthcare providers and mothers regarding sexual problems [14]. Therefore, during this transitional period, it is crucial for women to receive psychological counseling, highlighting the importance of midwives and healthcare professionals addressing this vital issue [1]. World Health Organization (WHO) has always emphasized that in maternal and newborn care, providing sexual information and counseling to women based on their needs is an ideal opportunity to address problems related to sexual health and sexual function [15]. Midwife-led couple counseling has demonstrated beneficial outcomes in addressing issues of sexual satisfaction across diverse populations [16-18]. It has proven effective in improving sexual satisfaction and desire among women experiencing postpartum sexual dysfunction [19].

Our extensive search in available databases has revealed a significant gap in research. To our knowledge, no randomized controlled trial study has been conducted on the effect of midwife-led integrative couple counseling on SDD in postpartum couples, either in Iran or internationally. This study, therefore, represents a novel and important contribution to the field of sexual health and postpartum care.

Materials and Methods

Aim

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the effect of midwife-led integrative couple counseling on SDD in couples after childbirth. The specific aim is to assess and compare the level of SDD between the intervention and control groups at three time points: before the intervention, immediately after, and four weeks post-intervention.

Study design

This study is a randomized clinical trial with two parallel arms: An intervention group and a control group.

Setting of the study

The participants in this study will be couples who have recently given birth and are attending health centers or urban family physician clinics in Sari, Iran.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria are as follows: written informed consent from both partners; women of childbearing age (aged 18 to 54) ; a minimum of 10 weeks postpartum [20-22]; cohabitation with a spouse; access to a smartphone (for completing forms and questionnaires); availability for the duration of the study; absence of chronic physical illnesses; no history of substance abuse; not currently pregnant; no diagnosed psychological disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety, or stress based on the DASS-21); no physical conditions interfering with sexual function; no use of psychiatric medications; no participation in educational or counseling programs related to sexual functioning in the past six months; and no history of genital or pelvic surgeries (e.g. hysterectomy) that could impact sexual desire.

Sample size and sampling method

Based on the study by Mintz et al. [23], the Mean±SD of sexual desire scores (measured using the Hulbert index of sexual desire [HISD]) was reported as 52.44±13.20 in the intervention group and 37.01±12.74 in the control group. Using these values, and assuming a significance level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.8, the required sample size was calculated to be 12 participants. Considering an estimated 35% attrition rate, the final sample size was adjusted to 16 participants, with 16 couples in the intervention group and 16 couples in the control group (Equation 1).

Sampling will be conducted using a convenience sampling approach. After receiving approval from the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, the researcher will register the trial on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), obtain an official letter of introduction, and proceed to visit health centers and urban family physician clinics in Sari, Iran. At these centers, eligible participants will be identified based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria through the local PARSA health database. Those meeting the criteria and expressing interest in the study will be invited to participate. A list of eligible and willing participants will be compiled, and their information will be coded in an Excel spreadsheet using identification codes instead of personal identifiers. The time schedule for conducting each parts of the study is presented in Table 1.

Random allocation

In this study, participants will be matched based on the duration of marriage, number of deliveries (parity), breastfeeding status and age. Random allocation into intervention and control groups will be performed using a block randomization method. Two-couple blocks will be used, with the possible arrangements being “TC” and “CT,” where “T” represents the intervention group and “C” the control group. Block assignment will be determined using the RANDBETWEEN function in Excel, generating random numbers between 1 and 2. A value of 1 will correspond to the “CT” block, and a value of 2 to the “TC” block. Based on the generated sequence, participants will be randomly assigned to the respective groups.

Blinding

Given the nature of the intervention, participant blinding in the intervention group is not feasible. Therefore, blinding will be implemented at the outcome assessor and data analyst (statistician) levels. To ensure blinding, after the intervention sessions are completed, a research assistant will distribute the questionnaires to the participants. Once completed, the participants will place their questionnaires into a sealed box, with the groups labeled as “A” and “B” to conceal group identity. Additionally, all collected data will be anonymized and sent to the statistician using coded identifiers for analysis. The study procedure is illustrated in the CONSORT flowchart (Figure 1).

Equipment

Data collection tools

The data collection instruments in this study include a demographic information form, the HISD, the depression anxiety stress scales-21 (DASS-21), and the index of sexual satisfaction (ISS) by Hudson. Before the intervention begins, the links to the questionnaires on Porsline will be provided to the couples. Immediately after the counseling sessions end, a post-test and a follow-up session will be conducted four weeks [24] and three month [25] later to reassess and compare the two groups in terms of SDD and sexual satisfaction.

The demographic questionnaire consists of four sections: Socio-demographic characteristics, pregnancy and childbirth history, sexual history, and medical history. The content validity of this form will be confirmed by a panel of experts from Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, specializing in midwifery, reproductive health, and psychology.

Primary outcome measures

SDD: In this study, SDD will be assessed through two approaches: At the individual level and at the couple/group level.

At the individual level, participants will respond to a single-item question: “Do you feel that you and your partner are at almost the same level of sexual desire?”.

At the couple and group level, desire discrepancy will be calculated using the HISD by measuring the standardized difference between partners’ sexual desire scores. To assess whether there is a meaningful difference between women’s and their husbands’ levels of sexual desire, the Z-score test is used. Specifically, the Z-score of the male partner will be subtracted from the Z-score of the female partner (Z-woman–Z-man). If the absolute value of the Z-score exceeds 1.96 (at a 95% confidence level [CI]), we can conclude that the difference in sexual desire between the couple is statistically significant. On the other hand, if the Z-score falls between -1.96 and +1.96, it indicates that the difference is not statistically significant (Equation 2) [10, 26].

The HISD, developed by Apt and Halbert, has demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability [27]. In a study conducted by Ahmadnia et al. (2020), the content and face validity of the instrument were confirmed, and internal consistency was verified with a Cronbach’s α of 0.87 [28].

Secondary outcome measures

Sexual satisfaction: Sexual satisfaction will be evaluated using the Hudson sexual satisfaction questionnaire, developed by Hudson et al. in 1981. This instrument consists of 25 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, assessing various aspects of sexual satisfaction [29]. The original version of the questionnaire was designed to measure marital satisfaction in 70 couples and has demonstrated acceptable validity [29]. In a study conducted by Shams Mofaraheh at Iran University of Medical Sciences, the Persian version of the Hudson sexual satisfaction questionnaire was standardized and shown to have strong psychometric properties. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α, which yielded values of 0.93 for the fertile group and 0.89 for the infertile group [30].

To assess participants’ levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, the DASS-21 will be utilized. This scale was originally developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) and further analyzed by Antony et al. who confirmed the three-factor structure, depression, anxiety, and stress. The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) for these subscales was reported as 0.97, 0.92, and 0.95, respectively [31]. In Iran, Asghari et al. validated the Persian version of the DASS-21, confirming its reliability and construct validity. The reliability coefficient for the total scale was reported as r=0.91 [32].

Data management

Participants will be assured that all data will be collected and handled in accordance with strict confidentiality principles. Data will be collected anonymously and encoded to protect participants’ identities. Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. To respect participants’ autonomy, they will be informed that participation is voluntary, and that they may withdraw from the study at any time without any impact on their access to medical or health services. Additionally, to ensure privacy and comfort, all counseling sessions will be held in a private and soundproof setting.

Interventions

After selecting eligible participants, access links to the demographic questionnaire, the DASS-21, and the HISD will be provided to the couples. Participants who score in the severe to extremely severe range for depression, anxiety, or stress in the DASS-21 will be excluded from the study and referred to a psychiatrist. As mentioned, SDD in couples will be assessed in two ways: At the individual level and at the couple/group level. At the individual level (which, in fact, serves as the inclusion criterion for identifying SDD), discrepancy will be measured using a single question: “Do you feel that you and your partner are at almost the same level of sexual desire?” Possible answers will be yes (0) and no (1). Individuals who do not report a discrepancy at the individual level will not be included in the study. At the couple/group level (after the completion of sampling and after all couples have responded to the questionnaire, the quantitative and statistical calculation of SDD between couples will be conducted), desire discrepancy will be calculated using scores from the Halbert sexual desire index. The difference between standardized scores (Z-scores) of each couple will be used—specifically, the man’s Z-score will be subtracted from the woman’s Z-score [10]. Positive scores indicate that the woman has a higher level of desire than her male partner; negative scores indicate the opposite. A Z-score with a 95% CI>1.96 will be considered significant. Finally, 32 couples will be enrolled in the study after providing informed consent. Participants will be randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group using blocked randomization, with 16 couples in each group. The couple counseling sessions will last approximately 60 minutes [33] and take place over five sessions (6 weeks). In addition, the sessions will be conducted remotely through secure video conferencing (e.g. Google Meet or WhatsApp) to ensure accessibility and convenience [34]. The counseling sessions are conducted by a master’s student in midwifery counseling. prior to initiating the interventions, she has participated in specialized workshops on sexual health, treatment of sexual dysfunctions, and couples counseling, and holds valid certifications in these areas. Participants will be contacted once or twice per week to ensure homework completion. The homeworks given to the couples will consist of the same educational content provided during each session. They will be asked to regularly practice these skills throughout the week in order to enhance intimacy and improve their relationship interactions. In the first session, before the intervention begins, the Hudson sexual satisfaction questionnaire will be administered to both partners to allow for comparison of pre- and post-intervention scores. Post-tests will be administered immediately after the final session, and a follow-up session will take place four weeks [24] and three month [25] later to reassess SDD and sexual satisfaction in both groups.

Midwife-led integrative couple counseling

In the intervention group, integrative couple counseling will be conducted by a trained researcher who has completed certified training in couples counseling and the treatment of sexual disorders. Each couple in the intervention group will participate in five 60-minute sessions of integrative couple counseling (Table 2).

Control group

The control group will receive routine care, including standard midwifery care and treatments following delivery (such as performing papsmear, treating vaginal infections, managing potential anemia and so on). The same questionnaires will be administered at all stages concurrently with the intervention group.

Protocol deviation

Deviations or violations of the study protocol may occur and will be documented and reported. In cases where participants are excluded from the study for any reason, the reasons for withdrawal will be recorded. The data from these participants will be analyzed using the intention-to-treat (ITT) approach.

Modification to the protocol

Any changes in procedure that may affect the study’s conduct, the patient’s potential benefits, or the patient’s safety, including changes in study objectives, study design, patient population, sample size, the study method or important administrative aspects will require the official documents of this amendment with the approval of the research team and the approval of the ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

The data will be collected individually from participants in both the intervention and control groups, and the difference in sexual desire will be calculated for each. Since sexual desire is measured at four different time points (pre-intervention, five weeks after the start of the intervention, four weeks and three month post-intervention), various statistical tests will be used depending on whether the normality assumption is met (tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test): The normality of quantitative data will be assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests, and equality of variances will be examined using Levene’s test and the F-test. If the data meet normality assumptions: an independent samples t-test will be used for between-group comparisons, a paired t-test will assess within-group changes, repeated measures ANOVA will evaluate changes over time between the two groups. A mixed-effects model will also be applied to account for within-subject correlations and to control for potential confounding variables. If the normality assumption is not met: Non-parametric tests such as the Mann–Whitney U test (between-group), the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (within-group), and the Friedman test (for repeated measures) will be employed. Additionally, the generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach will be used for analyzing repeated measures data in a non-parametric framework. The effect size and its 95% CI will be calculated for each outcome to determine the clinical significance of findings. A significance level of 0.05 will be considered for all statistical analyses. Data analysis will be conducted using SPSS software, version 22.

Discussion

The current study aims to determine the effectiveness of five-session integrative couple counseling for couples after their delivery with SDD. Couples generally experience a significant decrease in postpartum sexual activity due to hormonal changes and adherence to the role of parents [35]. Changes in the roles and responsibilities of partners as new parents, lack of private time as a couple, increased stress, and fatigue have been suggested as explanations for decreased desire and sexual activity after the birth of the baby [36, 37]. The high incidence of SDD [2, 9], coupled with its potential to exacerbate relational conflicts [2] and diminish overall relationship satisfaction [10, 12], emphasizes the need for targeted interventions. Vowels et al. aim to “effect an online sex therapy program without a therapist on the treatment of couples’ SDD. “ A case study of 10 people found that using couple strategies and treatments instead of focusing on the individual helped improve and treat [4].

Current results show that SDD is significantly associated with sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction [4, 10-12]. Kleinplatz et al. conducted a group therapy intervention to improve sexual satisfaction in 14 couples with low sexual desire or SDD, which was associated with increasing sexual satisfaction and satisfaction with the intensity of sexual arousal, variety, and frequency of sex [38]. Zamani et al. conducted a clinical trial on 75 postpartum women with low sexual satisfaction who received four sexual counseling sessions based on the womens postpartum sexual health program (WPSHP), including three group sessions and one couple counseling session. They showed a significant improvement in sexual satisfaction scores in the intervention group [19]. Aghababaei et al. conducted a clinical trial study to determine the effectiveness of sexual health counseling on the sexual function of 104 lactating women with low sexual desire. Weekly sessions for 4 weeks were based on the rapport building, exploration, decision making, and implementing the decision (REDI) model, which was associated with an increase in female sexual function index (FSFI) in the intervention group [39]. Our study is based on the results of studies that highlight the prevalence and distress associated with postpartum SDD [9].

In order to design the intervention in the present study, an integrative couples counseling approach was used, which has evidence of its effectiveness in improving sexual disorders in previous studies. A study by Samadi et al. was designed and implemented as a randomized clinical trial with 24 couples suffering from hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). Participants were randomly assigned to two groups: Intervention and control. The intervention group received integrative couples counseling treatment, which consisted of 10 sessions, once a week, for 90 minutes. The instruments used in this study included the HISD, FSFI and international index of erectile function (IIEF), which was administered at pre-test, post-test, and eight-week follow-up. The results showed that couples in the intervention group, especially women, experienced a significant increase in sexual desire, and this improvement was maintained at the follow-up stage [40]. In a study conducted by Nezamalmolki et al., 30 women experiencing marital infidelity underwent 9 sessions of 90-minute integrative couples counseling in a quasi-experimental design (pre-test–post-test–3-month follow-up). These interventions included cognitive-behavioral techniques, emotion regulation, and programs to promote marital intimacy and sexual health. The results of this study showed that therapists were able to significantly increase sexual functioning and marital intimacy and reduce impulsivity; and these positive changes were sustained up to three months after the end of treatment [41]. The effectiveness of couple strategies, such as increasing communication and sexual intimacy, over individual strategies [4] supports the rationale for our focus on midwife-led integrative couple counseling. Integrative couple counseling, with emphasis on circular causality and the collaborative nature of change, offers a promising approach to mitigating SDD [13]. The lack of clinical studies on this topic in Iran highlights the need for more local studies to ensure the applicability and relevance of integrative couples counseling in different cultural and social contexts. Also, our study highlights a gap in studies related to the use of midwife-led integrative couple counseling, specifically in the Iranian context. Based on the emphasis of The WHO on providing sexual information and counseling to women based on their needs in maternal and newborn care [15] and considering the positive effects of midwife-led couple counseling on addressing sexual satisfaction issues in different populations [16-18] and improving sexual satisfaction and sexual desire in women with sexual disorders after childbirth [19], it seems that the intervention of a midwife can be effective in this field.

This study protocol is subject to some limitations, such as restricted access to eligible participants and the impossibility of participant blinding due to the characteristics of the intervention, which may introduce potential bias.

Also, if the intervention shows promising results, the protocol may be shared with health policymakers and planners to support the potential integration of this approach into sexual health counseling and the management of SDD within primary health care (PHC) services.

Conclusion

Considering the negative consequences of SDD on the quality of couples’ relationships, including weakening emotional bonds, exacerbating marital conflicts, and increasing the psychological and emotional distance between couples, it can be said that this phenomenon not only challenges relationship stability, but also leads to reduced effective interactions, decreased sexual satisfaction, and ultimately decreased overall relationship satisfaction. Since the postpartum period is a critical and sensitive period in the common life of couples, and psychological, physiological, and new roles can affect couples’ relationships, the design and implementation of interventions aimed at reducing SDD and improving marital interactions during this period are of particular importance. The intervention in this study, focusing on promoting effective communication, mutual understanding, and setting sexual expectations in a healthy and supportive relationship, can play an effective role in reducing the negative effects of sexual desire differences and take steps to improve the sexual health and satisfaction of couples after delivery.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1403.304) and has been prospectively registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (Code: IRCT20161126031117N17). All ethical guidelines and codes of conduct will be strictly observed throughout the research process. All ethical principles regarding participants’ rights will be strictly upheld in this study. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants, and the confidentiality of their personal information will be fully guaranteed throughout the intervention.

Funding

This project was financially supported by the Student Research Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Investigation: Fatemeh Tousheh and Soghra Khani; Data collection: Armin Firoozi and Keshvar Samadaee Gelehkolaee and Fatemeh Tousheh; Writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Center and the Research and Technology Vice-Chancellor of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for approving the protocol, and after the completion of the study, the participants in the study are thanked.

References

- Banaei M, Moridi A, Dashti S. Sexual dysfunction and its associated factors after delivery: Longitudinal study in Iranian women. Mater Sociomed. 2018; 30(3):198-203. [DOI:10.5455/msm.2018.30.198-203] [PMID]

- Girard A, Woolley SR. Using emotionally focused therapy to treat sexual desire discrepancy in couples. J Sex Marital Ther. 2017; 43(8):720-735. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2016.1263703] [PMID]

- Zilbergeld B, Ellison CR. Desire discrepancies and arousal problems in sex therapy. In: Leiblum SR, Pervin LA, editors. Principles and practice of sex therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1980. [Link]

- Vowels LM. An online sensate focus application to treat sexual desire discrepancy in intimate relationships: Contrasting case studies. Sex Relat Ther. 2023; 38(3):411-30. [DOI:10.1080/14681994.2022.2026316]

- Marieke D, Joana C, Giovanni C, Erika L, Patricia P, Yacov R, et al. Sexual desire discrepancy: A position statement of the european society for sexual medicine. Sex Med. 2020; 8(2):121-131. [DOI:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.02.008] [PMID]

- Kim JJ, Muise A, Barranti M, Mark KP, Rosen NO, Harasymchuk C, et al. Are couples more satisfied when they match in sexual desire? New insights from response surface analyses. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2021; 12(4):487-96. [DOI:10.1177/1948550620926770]

- Vowels LM, Mark KP. Strategies for mitigating sexual desire discrepancy in relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2020; 49(3):1017-28. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-020-01640-y] [PMID]

- Galizia R, Theodorou A, Simonelli C, Lai C, Nimbi FM. Sexual satisfaction mediates the effects of the quality of dyadic sexual communication on the degree of perceived sexual desire discrepancy. Healthcare. 2023; 11(5):648. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare11050648] [PMID]

- Rosen NO, Bailey K, Muise A. Degree and direction of sexual desire discrepancy are linked to sexual and relationship satisfaction in couples transitioning to parenthood. J Sex Res. 2018; 55(2):214-25. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2017.1321732] [PMID]

- Davies S, Katz J, Jackson JL. Sexual desire discrepancies: effects on sexual and relationship satisfaction in heterosexual dating couples. Arch Sex Behav. 1999; 28(6):553-67. [DOI:10.1023/A:1018721417683] [PMID]

- Mark KP. Sexual desire discrepancy. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2015; 7:198-202. [DOI:10.1007/s11930-015-0057-7]

- Willoughby BJ, Farero AM, Busby DM. Exploring the effects of sexual desire discrepancy among married couples. Arch Sex Behav. 2014; 43(3):551-62. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-013-0181-2] [PMID]

- Young ME, Long LL. Counseling and therapy for couples. Belmont: Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co; 1998. [Link]

- Yeniel AO, Petri E. Pregnancy, childbirth, and sexual function: Perceptions and facts. Int Urogynecol J. 2014; 25(1):5-14. [DOI:10.1007/s00192-013-2118-7] [PMID]

- Abdool Z, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Postpartum female sexual function. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009; 145(2):133-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.04.014] [PMID]

- Salehi S, Mahmoodi Z, Jashni Motlagh A, Rahimzadeh M, Ataee M, Esmaelzadeh-Saeieh S. Effect of midwife-led counseling on the quality of life of women with body image concerns during postpartum. J Holistic Nurs Midwifery. 2021;31(3):165-74. [DOI:10.32598/jhnm.31.3.2064]

- Masoumi SZ, Boojarzadeh B, Farhadian M, Mohagheghi H, Soltani F. The effect of counselling on the sexual satisfaction of women with hypoactive sexual desire referring to Hamadan health centres, 2017. Fam Med Prim Care Rev. 2020; 22(1):36-42. [DOI:10.5114/fmpcr.2020.92504]

- Naeij E, Khani S, Firouzi A, Moosazadeh M, Mohammadzadeh F. The effect of a midwife-based counseling education program on sexual function in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Menopause. 2019; 26(5):520-30. [DOI:10.1097/GME.0000000000001270] [PMID]

- Zamani M, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Moradi M, Esmaily H. The effect of sexual health counseling on women's sexual satisfaction in postpartum period: A randomized clinical trial. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2019; 17(1):41–50. [DOI:10.18502/ijrm.v17i1.3819] [PMID]

- Edosa Dirirsa D, Awol Salo M, Eticha TR, Geleta TA, Deriba BS. Return of sexual activity within six weeks of childbirth among married women attending postpartum clinic of a teaching hospital in Ethiopia. Front Med. 2022; 9:865872. [DOI:10.3389/fmed.2022.865872] [PMID]

- Gadisa TB, G/Michael MW, Reda MM, Aboma BD. Early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse and its associated risk factors among married postpartum women who visited public hospitals of Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Plos One. 2021; 16(3):e0247769. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0247769] [PMID]

- Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005; 31(1):1-20. [DOI:10.1080/00926230590475206] [PMID]

- Mintz LB, Balzer AM, Zhao X, Bush HE. Bibliotherapy for low sexual desire: Evidence for effectiveness. J Couns Psychol. 2012; 59(3):471-8. [DOI:10.1037/a0028946] [PMID]

- Nezamnia M, Iravani M, Bargard MS, Latify M. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on sexual function and sexual self-efficacy in pregnant women: An RCT. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2020; 18(8):625-36. [DOI:10.18502/ijrm.v13i8.7504] [PMID]

- Farahi Z, HashemZadeh M, Farnam F. Sexual counseling for female sexual interest/arousal disorders: A randomized controlled trial based on the "good enough sex" model. J Sex Med. 2024; 21(2):153-62. [DOI:10.1093/jsxmed/qdad168] [PMID]

- Schäfer T, Schwarz MA. The meaningfulness of effect sizes in psychological research: Differences between sub-disciplines and the impact of potential biases. Front Psychol. 2019; 10:813. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00813] [PMID]

- Apt CV, Hurlbert DF. Motherhood and female sexuality beyond one year postpartum: A study of military wives. J Sex Educ Ther. 1992; 18(2):104-14. [DOI:10.1080/01614576.1992.11074044]

- Ahmadnia E, Keramat A, Ziaei T, Yunesian M, Nazari AM, Kharaghani R. Psychometric assessment of the Persian version of the hurlbert index of sexual compatibility. Sex Cult. 2021; 25:584-96. [DOI:10.1007/s12119-020-09784-8]

- Hudson WW, Harrison DF, Crosscup PC. A short‐form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. J Sex Res. 1981; 17(2):157-74. [DOI:10.1080/00224498109551110]

- Shams Mofaraheh Z, Shahsiah M, Mohebi S, Tabaraee Y. [The effect of marital counseling on sexual satisfaction of couples in Shiraz city (Persian)]. J Health Syst Res. 2011; 6(3):417-24. [Link]

- Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess. 1998; 10(2):176-81. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176]

- Asghari A, Saed F, Dibajnia P. [Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales-21 (DASS-21) in a non-clinical Iranian sample (Persian)]. Int J psychol. 2008; 2(2):82-102. [Link]

- Bouchard KN, Bergeron S, Rosen NO. Feasibility of a cognitive-behavioral couple therapy intervention for sexual interest/arousal disorder. J Sex Res. 2025; 62(5):765-75. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2024.2333477] [PMID]

- Kysely A, Bishop B, Kane RT, McDevitt M, De Palma M, Rooney R. Couples therapy delivered through videoconferencing: Effects on relationship outcomes, mental health and the therapeutic alliance. Front Psychol. 2022; 12:773030. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.773030] [PMID]

- Avery MD, Duckett L, Frantzich CR. The experience of sexuality during breastfeeding among primiparous women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2000; 45(3):227-37. [DOI:10.1016/S1526-9523(00)00020-9] [PMID]

- Woolhouse H, McDonald E, Brown S. Women's experiences of sex and intimacy after childbirth: Making the adjustment to motherhood. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2012; 33(4):185-90. [DOI:10.3109/0167482X.2012.720314] [PMID]

- Ahlborg T, Dahlöf LG, Hallberg LR. Quality of intimate and sexual relationship in first-time parents six months after delivery. J Sex Res. 2005; 42(2):167-74. [DOI:10.1080/00224490509552270] [PMID]

- Kleinplatz PJ, Paradis N, Charest M, Lawless S, Neufeld M, Neufeld R, et al. From sexual desire discrepancies to desirable sex: Creating the optimal connection. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018; 44(5):438-49. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405309] [PMID]

- Aghababaei S, Refaei M, Roshanaei G, Rouhani Mahmoodabadi SM, Heshmatian T. The effect of sexual health counseling based on REDI model on sexual function of lactating women with decreased sexual desire. Breastfeed Med. 2020; 15(11):731-8. [DOI:10.1089/bfm.2020.0057] [PMID]

- Samadi P, Alipour Z, Maasoumi R. Evaluating an integrated approach to improve the couple sexual desire disorders: A Randomized clinical trial study. Iran J Public Health. 2024; 53(6):1457-166. [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v53i6.15919] [PMID]

- Nezamalmolki M, Bahrainian SA, Shahabizadeh F. Effectiveness of integrative couple therapy on sexual function, marital intimacy, and impulsivity in women affected by marital infidelity. J Assess Res Appl Couns. 2024; 6(2):19-26. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jarac.6.2.3]

Type of Study: Study protocol |

Subject:

Midwifery

Received: 2025/06/11 | Accepted: 2025/09/19 | Published: 2025/09/19

Received: 2025/06/11 | Accepted: 2025/09/19 | Published: 2025/09/19

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |