Tue, Nov 18, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 2, Issue 4 (Summer 2024)

CPR 2024, 2(4): 259-270 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abedian Kasgari K, Aghaei N. The Needs and Problems of Bereaved Families in Hospitals: Perspectives of the Bereaved Families and Medical Staff. CPR 2024; 2 (4) :259-270

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-140-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-140-en.html

Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Center, Mazandaran University of medical sciences, Sari, Iran. & Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 679 kb]

(31 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (315 Views)

References

Full-Text: (12 Views)

Introduction

Grief is an emotional reaction to the loss of a beloved one [1]. Every person may experience grief and sorrow at some point in their life [2]. At older ages, grief and bereavement are more common [3] and can be a very stressful experience for the families [1]. As people become older, they have to accept and adapt to the death of a loved one [4]. Depending on the nature of death, the reactions of bereaved people vary. For example, in the case of an imminent death, bereaved people may express uncertainty, fear, and sorrow, which can have adverse effects on their health [2]. Grief among the caregivers of cancer patients can lead to more intense sadness and more unfavorable consequences [5]. The majority of people often adjust to the loss of a loved one and continue their lives within a few months; however, some may experience prolonged and more intense grief [4], which has psychophysical and economic risks for their relatives [6] and can affect the social and emotional well-being of the bereaved person.

Most people die in hospitals, and the in-hospital care providers often encounter bereaved people [7]. The death of a patient in a hospital has a negative psychological impact on their families [8]. Support of bereaved family members is a part of care, which includes providing information and emotional support [8]. Research is required to identify and discover effective strategies in this field to help reduce the post-death grief of the bereaved people [5]. The current screening and support of the bereaved people are not enough. It is obviously necessary for the intensive care units to provide screening services and bereavement follow-up for family members [4].

Various quantitative and qualitative studies have been conducted on grief and the problems of the bereaved people [4, 9-13]. However, no research has investigated the needs and problems of the bereaved people from the perspectives of the medical staff. Therefore, considering the importance of support for the bereaved people and their satisfaction, the present study aims to explore the needs and problems of the bereaved people perceived by hospital staff in Iran. By identifying the needs and problems of bereaved families, we can develop effective strategies to meet their needs and address their concerns within hospitals.

Materials and Methods

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted from June 3, 2016, to October 7, 2017. The study population consists of all medical staff working in teaching/medical hospitals in Sari, Iran (Imam Khomeini, Bu-Ali Sina, Fatemeh Zahra, and Zare) affiliated with Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, who are in direct contact with bereaved families from hospital admission to discharge, as well as bereaved families who had lost a loved one in these centers in the past year.

The inclusion criteria for medical staff were a direct interaction with bereaved families and willingness to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria for bereaved families were being relatives of the deceased, who were seeking to discharge the body of the deceased person within the mentioned period. For both groups, the exclusion criterion was the lack of answers to 20% of the questions on the questionnaire. A census sampling method was used for selecting medical staff bereaved families. After approval from the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences and obtaining permission from the hospitals, the researcher visited the hospitals for sampling.

The data collection tools included a demographic checklist and two researcher-made questionnaires to examine the needs and problems of the bereaved people from the perspectives of medical staff and bereaved families. The demographic checklist surveyed information about the deceased person (gender, marital status, cause of death), the families of the deceased person (gender, marital status, relationship with the deceased), and the medical staff (age, gender, marital status, educational level, type of employment, and serving place). The questionnaire that surveys the needs and problems of the bereaved people from the perspective of medical staff has 29 items, and the questionnaire that surveys the perspectives of bereaved families has 26 items, both based on a Likert scale from 1 (absolutely agree) to 4 (absolutely disagree). Both questionnaires measure needs and problems in three areas of welfare, support, and communication. In the questionnaire surveying the perspectives of medical staff, items 1, 2, 16 are the communication domain, items 3,7,8,9, 17,18, 19, 26, 27, and 29 for the support domain, and items 4,5,6,10,11-15,20,21-25, and 28 for the welfare domain. In the questionnaire surveying the bereaved families’ perspectives, items 2-8 and 15 are for the communication domain, items 1,9, 20,21,23,25, and 26 for the support domain, and items 10-19,22, and 24 for the welfare domain. A lower score indicates greater needs and problems. Finally, both groups also answered two open-ended questions to measure their satisfaction.

The validity of the questionnaires was assessed qualitatively and quantitatively based on the opinions of 11 faculty members of the Nasibeh School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, and corrections were applied based on their comments. A content validity index (CVI) of 0.88 and content validity ratio (CVR) of 0.72 was reported the questionnaire surveying the perspectives of medical staff. For the questionnaire surveying the perspectives of bereaved families, CVI=0.93 and CVR=0.74. The Cronbach’s α for the two questionnaires was found to be 0.86 and 0.90, respectively.

Before distributing the questionnaire, the study objectives and methods were explained to the participants, and their informed consent was obtained. Depending on the conditions of the bereaved families, the questionnaires were completed sequentially or intermittently. For the medical staff, the questionnaires were delivered to the head nurse or unit manager. Then, the researcher visited the units to collect the completed questionnaires. The collected data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 22 using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, descriptive statistics (frequency, Percentage, Mean±SD), Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Spearman’s correlation test.

Results

Participants included 257 medical staff and 102 bereaved families. The majority of the deceased people were male and married (52.9%), and the most common cause of their death was disease (76.5%). Most of the bereaved family members were male (58.8%), married (74.5%), and the deceased individuals’ children (82.4%). The medical staff were in the age range of 23-55 years (Mean±SD, 33.94±7.71 years); 80.9% (n=208) were female, 75.1% (n=198) were married, 84.8% had a bachelor’s degree (n=218), and 36.2% (n=93) had permanent employment (Table 1).

The needs and problems from the perspective of medical staff

About 73% of medical staff perceived the presence of the patient’s first-degree relatives at the end of life stage as necessary, while 80% stated that the presence of a chaplain at the end of life can provide emotional comfort to the relatives. More than 90% stated that the existence of a separate unit in the hospital for decedent affairs can be helpful for both the families and the medical staff. More than 90% believed that informing the families about the patient’s death is a difficult task for them and that they do it out of compulsion. Also, 94% perceived it necessary to have a liaison officer in the hospital to inform the families about the patient’s death. More than 97% stated that the presence of all bereaved relatives in the ward can bother other patients. Furthermore, 80% stated that the presence of only one first-degree relative when transferring the deceased person from the ward to the mortuary is sufficient, and when there is no companion, the medical staff can better perform the tasks related to the deceased person. Moreover, 98% stated that seeing the bereaved people upon entering the hospital makes them uncomfortable, and 92% recommended the presence of a gathering hall in the hospital to avoid seeing heartbreaking scenes when starting to work. Also, most medical staff opposed the idea that referring the deceased to the morgue could cause severe dissatisfaction among grieving relatives (Table 2).

Based on two open-ended questions, from the perspective of medical staff, the obvious needs and problems of the bereaved families included the bereaved families’ lack of awareness of the services provided to the patient, lack of timely informing the families about of the patient’s dying conditions, absence of a social worker after the patient’s death, observation of the resuscitation stages and the patient’s death by the families, delay in visiting doctors to write a summary of the case and issue a death certificate (delay in issuing a burial permit), along with the grief of losing a loved one and the heavy medical costs.

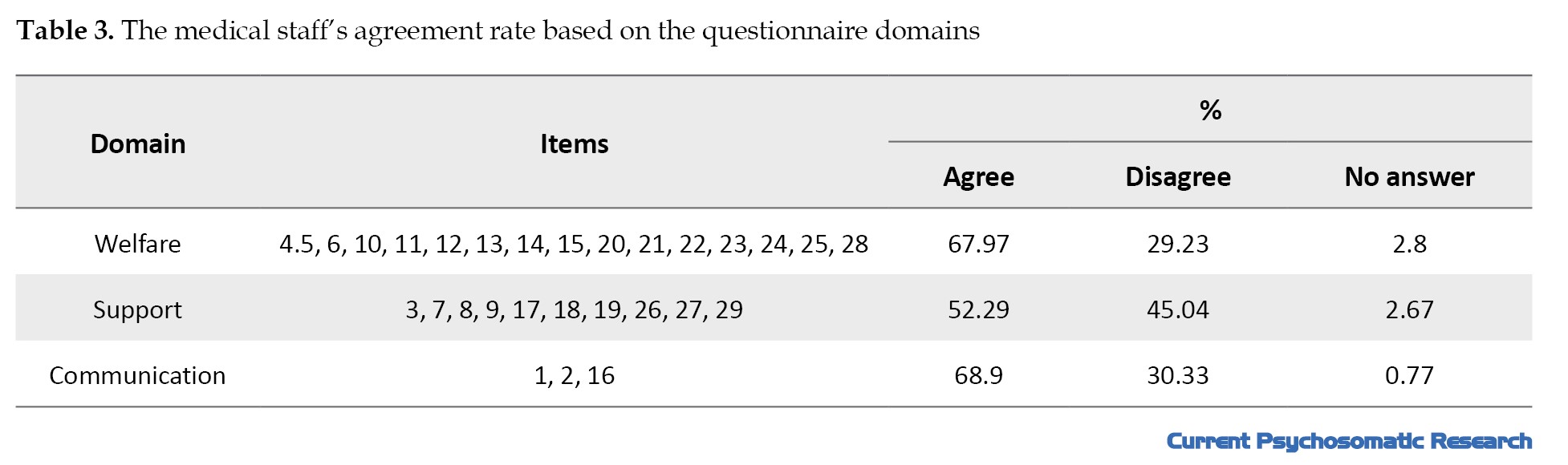

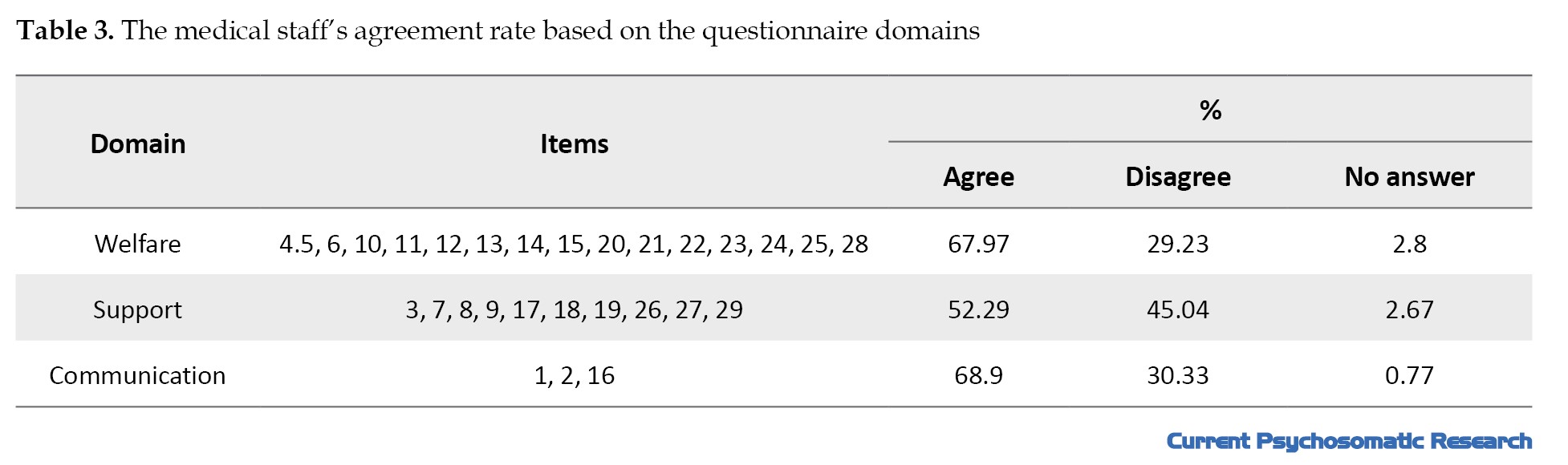

The mean score of the questionnaire surveying the perspective of the medical staff was 62.24±7.4, ranging 42-79. The highest agreement rate was related to the communication domain, followed by the welfare and support domains, and the highest disagreement rate was related to the support domain, followed by communication and welfare domains (Table 3).

In examining the difference in the mean scores of this questionnaire based on the demographic characteristics of medical staff, the results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed a statistically significant difference between males and females (P=0.009). However, based on the Kruskal-Wallis test results, no statistically significant difference was observed based on marital status (P=0.848), education level (P=0.294), or type of employment P=0.011 (Table 1). Also, based on the Spearman correlation test, there was a statistically significant relationship between the factors of age (r=-0.308, P<0.001) and work experience (r=-0.332, P<0.001) and the questionnaire score.

The needs and problems from the perspective of bereaved families

More than 90% of bereaved families stated that they needed to be with their patient in the ward during his/her end-of-life moments. More than 90% agreed that there is a need for a separate unit in the hospital to deal with the affairs of the deceased person and that this unit should support them to assess their mental and emotional state. About 97% agreed that if the families do not have enough money at the time of discharge, they should accept the deceased person’s ID card and discharge him/her. About 94% reported the need to receive transportation services at the discharge unit (Table 4).

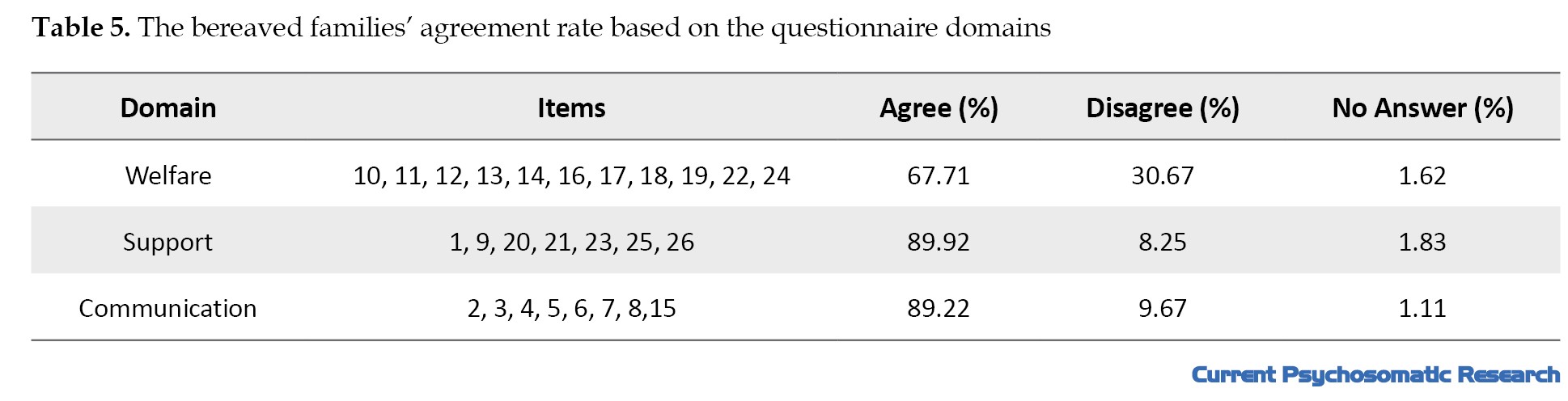

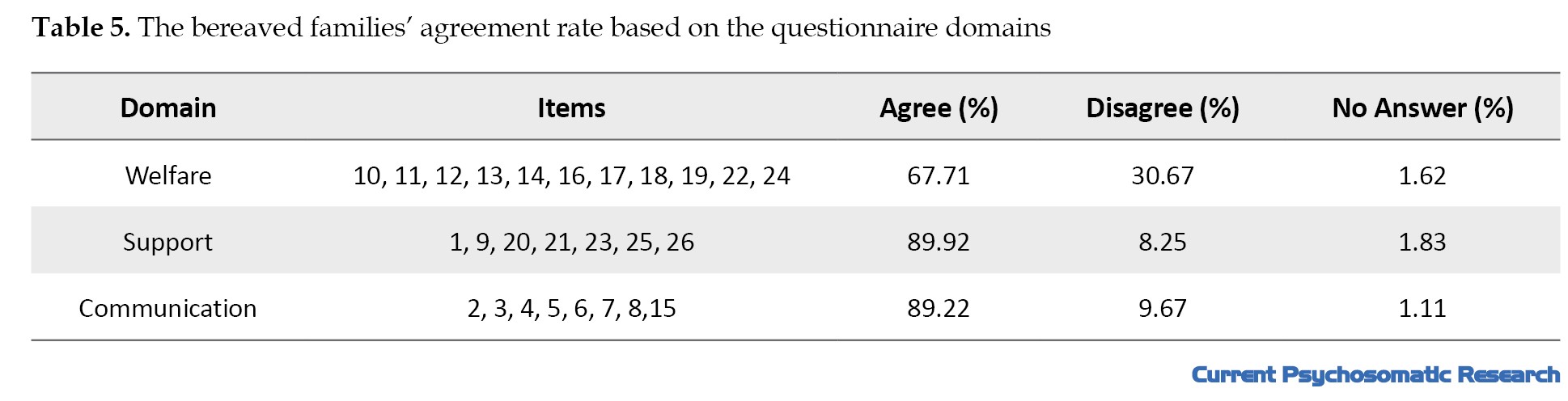

The mean score of the questionnaire surveying the perspective of bereaved families was 66.04±6.97, ranging 52-86. The highest agreement rate was related to the support domain, followed by communication and welfare dimensions, while the highest disagreement rate was related to the welfare domain, followed by communication and support domains (Table 5).

In examining the difference in the mean scores of this questionnaire based on the demographic characteristics of bereaved families, the results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed no statistically significant difference between males and females (P=0.126). Based on the Kruskal-Wallis test, there was no statistically significant difference based on the marital status (P=0.176), occupation (P=0.355), or relationship with the deceased person (P=0.640). However, this difference was statistically significant in terms of education level (P=0.026) (Table 1). Based on the Spearman correlation test, age had no statistically significant relationship with the questionnaire score (P=1.000).

Discussion

Based on the results of the present study, the perceptions of bereaved families and medical staff regarding the needs and problems of bereaved families in the hospital were almost similar and at an moderate level, indicating the bereaved families’ challenges in dealing with the deceased person’s affairs and they need supportive measures and targeted interventions from the relevant authorities to address their needs and problems. A statistically significant difference was found in the perceptions of families based on educational level; people with a higher level of education have a greater ability to recognize and express the needs and problems of bereaved families due to greater access to information resources, better coping skills, or a deeper psychological understanding of the grieving process. Also, a statistically significant difference was reported in the perceptions of medical staff based on age, work experience, and gender, which indicates the effect of these factors (age, work experience, and gender). Older and experienced medical staff, due to higher knowledge and experience, previous experience of dealing with the bereaved families, and higher skills in dealing with psychological issues, have a deeper perception of grief and achieve a better understanding of the needs of the grieving families. Differences in perspectives of medical staff based on gender can be due to different reactions, perceptions, and characteristics of men and women.

In the present study, we assessed the perception of both groups of bereaved families and medical staff regarding the needs and problems of bereaved families in three dimensions of welfare, support, and communication. According to the results of the present study, the need for a separate unit in the hospital to deal with the affairs of the deceased person, the need for a bereavement room in the hospital for bereaved relatives that provides catering services, and the need for transportation services for bereaved relatives in the discharge unit were among the needs perceived by bereaved families which were related to the welfare dimension. Wandering and wasting time to access an ambulance to transport the deceased person, to discharge the deceased person from the discharge unit, to perform payment checkouts in the Payment Counter, and to discharge the deceased person from the morgue were among the problems perceived by bereaved families, which were also related to the welfare dimension. Therefore, the prolonged process of settlement and delivering the deceased person’s body creates additional psychological pressure on families.

The medical staff mentioned the presence of the patient’s first-degree relatives in the end-of-life stage, the presence of a chaplain to provide emotional comfort to the families, the existence of a separate unit in the hospital (unit of decedent affairs), and the presence of a gathering hall in the hospital to avoid seeing the heartbreaking scenes, as the needs of the bereaved families which were related to the welfare dimension. The medical staff also mentioned the time-consuming process of the discharge of the deceased from the ward (due to delays in visiting doctors to write a summary of the case and issue a death certificate, delays in issuing a burial permit, and referring the deceased to the Forensic Medicine Organization), time-consuming process of payments for the discharge of the deceased from the discharge unit, financial and economic problems of families for the discharge of the deceased person, the lack of a bereavement room in the hospital with catering facilities, and the problems of families for finding an ambulance as the most important problems of the bereaved families which were also related to the welfare dimension.

Gray et al. [9], in a survey of bereaved families, categorized the results of the study into three areas: patient needs (maintaining health, appropriate medication prescription, adherence to patient wishes, physical presence in the patient’s final hours of life, and spiritual and religious end-of-life care), family and caregiver needs (enhanced communication with the patient’s care team, assistance with administrative challenges after death, emotional support, respect and valuing the patient’s life), and organizational facilities and characteristics (optimal staff care team coordination, presence of non-clinical staff for care, optimization of catering services, equipment and facilities for people with disabilities, provision of high-quality food), most of which are consistent with the results of the present study. Giorgali [14] in a study on the needs of bereaved families for bereavement services after the death of a child with cancer in Greece, stated that continuity of bereavement care from the care team, availability, individual care, an interdisciplinary approach, and contact with other bereaved parents were the key elements for providing bereavement services. In Boven et al.’s study [7], the provision of in-hospital bereavement services was also described as a caring behavior and challenge, and bereaved relatives appreciated all the services provided during bereavement. However, service providers, while recognizing the importance of bereavement care, stated that the provision of this care was challenged by several factors, such as insufficient training and time constraints. The results of Kruse et al.’s study [15] on supporting bereaved family members in the loss of children or adolescents also showed that grief counseling should be considered an essential component of health care for bereaved family members, because from the participants’ perspective, this counseling led to their comfort, adaptation, and faster return to daily life. The results of these studies are consistent with some of the results of the present study. Policymakers in Iran should be able to adopt policies using the experiences of the medical team for the bereaved families and take effective measures to provide welfare facilities, counseling services, and administrative and financial assistance to the bereaved families.

Among the needs and problems perceived by the bereaved families related to the support dimension, the need to be present in the ward during the patient’s last hours of life, the failure to transfer the deceased person to the morgue, the need for the Unit of Decedent Affairs to support them and assess their mental and psychological states, the need for a chaplain to be present in the hospital to provide mental and psychological support to the bereaved families, the need for a social worker to be present after the patient’s death, and acceptance of a valid ID card if the families did not have enough money to discharge the deceased person. In the present study, most of bereaved families stated that they had full support by medical staff in terms of performing procedures and they did not delay the time of discharge from the ward. The medical staff’s perceptions related to the support domain included: Families’ ability to meet the deceased person in the ward, the presence of a guide during the discharge of the deceased from the hospital, the presence of only one first-degree relative during the transfer of the deceased from the ward to the morgue, the unwillingness of the bereaved families to transfer the deceased person’s body from the ward to the morgue, as well as the observation of the resuscitation stages and the patient’s death by the patient companions.

In line with these results, several studies have indicated the need for emotional support for bereaved families. Thaqi et al. [16] showed that bereaved family members were satisfied with the patient’s end-of-life care. Information about the grief process and grief-related services was considered useful from their perspective. Researchers believe that the family should be considered as a unit to provide the opportunity for togetherness, mutual reflection, meaningful relationships, preparation for death, and resilience. Ito et al. [17] reported that the support and care needs of service providers such as lack of privacy due to poor design of the emergency department and presence during resuscitation, chaotic environment, and psychosocial reaction in grief, were the challenges in providing support and care to bereaved families, which indicates that emergency nurses need to better understand the experience of bereaved families. In the study by Kalocsai et al. [13] in Canada, nurses and physicians supported the provision of empathetic services to bereaved families. Emotional support is a vital type of support that clinicians are usually unable to provide to bereaved families due to having multiple tasks and responsibilities. Also, the results of Ó Coimín et al. [11] in Ireland showed that, although the quality of care provided by nurses, doctors, and other staff to bereaved families was highly rated, care in areas such as communication, emotional, and spiritual support still needed to be improved. Naef et al. [8] stated that there are many barriers to bereavement care in hospitals, and more research is needed to better understand the barriers and facilitators in the provision of bereavement care. They stated that a need-based guideline to the provision of bereavement care in hospitals is necessary to include the best practices and organizational support required. Also, according to the results of Aoun et al. [18] in Australia, a large gap is observed between the care services provided and the existing guidelines, which indicates that more research is needed in the field of underlying attitudes and patterns of bereavement support. In addition to developing guidelines, positive attitudes of service providers towards these guidelines and the participation of beneficiaries in sharing their experiences in the field of quality service provision are needed to modify the existing guidelines.

Regarding the communication dimension, most of the bereaved families agreed with the appropriateness of the treatment of the medical staff, the way of informing the patient’s death, and the way of transferring the deceased person from the ward to the morgue. The medical staff mentioned the difficulty of informing the families about the patient’s death and the need for a liaison officer in the hospital to inform the families about the patient’s death as the problems and needs related to the communication dimension. Haugen et al. [12] examined the perspectives of bereaved families in seven European and South American countries, and the results showed that there were many services available to provide care to dying patients, but there was still a need to improve skills in dealing with bereaved relatives. This suggests that communication challenges are not unique to a specific country; medical staff in all countries, even in those with advanced health systems, need to improve their communication with bereaved families. According to Aoun et al. [18], providing timely services and establishing effective communication play a crucial role in building trust in the services and focusing on the specific needs of bereaved families, rather than their general needs. In the study by Ito et al. [17], providing insufficient information and inappropriate transmission of bad news by medical staff were one of the care challenges raised by bereaved families. Most of the issues raised in these studies were also reported in the present study. However, there are some discrepancies that can be attributed to ethnic-cultural differences and varying family expectations across different cultures. For example, in the study by Ito et al. [17]only the experiences of bereaved people in the emergency departments were surveyed, where the conditions and emergency services, the anxiety of patient companions, and the lack of psychological preparation to accept bad news are different, which can be considered negative experiences for bereaved families. Overall, bereavement-related problems are a significant health issue, but there is lack of economic resources and investment for effective implementation of integrated bereavement care services at national levels [19]. Individual, family, and community-related indicators should be aligned with traditional medical indicators, respecting local cultures and contexts, to ensure that care systems are not only equitable but also responsive to diverse needs [20].

The limitations of this study included a small sample size and the risk of response bias due to the use of self-report tools, and the poor mental conditions of bereaved families and medical staff, which may affect their response to the questions. We offer the following policy recommendations based on the results of the present study:

I) Develop and implement comprehensive guidelines for caring for bereaved families and monitor their implementation:

1) focus on counseling and supportive services; 2) Provide information clearly that is understandable to the bereaved families, taking into account legal requirements and confidentiality of their information; 3) determine the level of family caregivers’ involvement in the end-of-life stage; 4) provide adequate information on the limitations of palliative care; 5) support according to the needs of bereaved families in a safe and ethical manner.

II) specialized communication training for medical staff, especially in the field of bereavement care:

1) issues related to grief should be included in the educational programs of medical staff; 2) necessary training should be provided to all medical staff on how to inform the bereaved families about bad news; 3) by improving appropriate communication between the doctor and the patient’s companions, timely information about the condition of the critically ill patient should be provided in an understandable and clear language.

III. Improving the welfare facilities in the hospital:

1) A quiet place with appropriate welfare facilities should be provided in the hospital for bereavement and the gathering of bereaved families; 2) the method of providing information and access to transportation and ambulance services for the transfer of the deceased person should be clarified in coordination with the relevant units.

IV. Facilitating administrative and financial processes related to the discharge of deceased people.

V. Establish specialized units and interdisciplinary teams for end-of-life care and bereaved families:

1) A team to deal with the affairs of deceased people, led by a trained person, should be established in the hospital to reduce the problems of the bereaved families; 2) trained personnel should be assigned to resolve the issues related to deceased individuals and carry out administrative procedures to achieve greater satisfaction with the provision of hospital services.

Pay special attention to spiritual and cultural support:

1) conditions for access to a chaplain should be provided to comfort the dying person and the bereaved families based on their religious beliefs and cultures; 2) medical staff should be aware of the cultural and spiritual sensitivities to death and bereavement, and facilities should be provided in the hospital to implement spiritual and religious programs. Designing interventions to respect the human aspect of care: An effort should be made to include issues related to grief and support for bereaved families in the educational and cultural programs of medical staff.

Conclusion

The results of the present study indicate that the problems and needs of bereaved families in hospitals are multidimensional. It is necessary to pay attention to the welfare, support, and communication dimensions of these problems and needs for bereaved families. Ethnic, cultural, and environmental differences, as well as individual differences, should be considered in the design of comprehensive interventions, as these differences have a significant impact on supporting bereaved families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1394.H102). Verbal consent was obtained from the participants. They were assured that their information would be kept confidential. All ethical principles were considered in the present study.

Funding

This study was part of the result of a research project approved and financially supported by Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: 2-94).

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences and all families and the medical staff of selected hospitals in Sari who participated in this study for their cooperation.

Grief is an emotional reaction to the loss of a beloved one [1]. Every person may experience grief and sorrow at some point in their life [2]. At older ages, grief and bereavement are more common [3] and can be a very stressful experience for the families [1]. As people become older, they have to accept and adapt to the death of a loved one [4]. Depending on the nature of death, the reactions of bereaved people vary. For example, in the case of an imminent death, bereaved people may express uncertainty, fear, and sorrow, which can have adverse effects on their health [2]. Grief among the caregivers of cancer patients can lead to more intense sadness and more unfavorable consequences [5]. The majority of people often adjust to the loss of a loved one and continue their lives within a few months; however, some may experience prolonged and more intense grief [4], which has psychophysical and economic risks for their relatives [6] and can affect the social and emotional well-being of the bereaved person.

Most people die in hospitals, and the in-hospital care providers often encounter bereaved people [7]. The death of a patient in a hospital has a negative psychological impact on their families [8]. Support of bereaved family members is a part of care, which includes providing information and emotional support [8]. Research is required to identify and discover effective strategies in this field to help reduce the post-death grief of the bereaved people [5]. The current screening and support of the bereaved people are not enough. It is obviously necessary for the intensive care units to provide screening services and bereavement follow-up for family members [4].

Various quantitative and qualitative studies have been conducted on grief and the problems of the bereaved people [4, 9-13]. However, no research has investigated the needs and problems of the bereaved people from the perspectives of the medical staff. Therefore, considering the importance of support for the bereaved people and their satisfaction, the present study aims to explore the needs and problems of the bereaved people perceived by hospital staff in Iran. By identifying the needs and problems of bereaved families, we can develop effective strategies to meet their needs and address their concerns within hospitals.

Materials and Methods

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted from June 3, 2016, to October 7, 2017. The study population consists of all medical staff working in teaching/medical hospitals in Sari, Iran (Imam Khomeini, Bu-Ali Sina, Fatemeh Zahra, and Zare) affiliated with Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, who are in direct contact with bereaved families from hospital admission to discharge, as well as bereaved families who had lost a loved one in these centers in the past year.

The inclusion criteria for medical staff were a direct interaction with bereaved families and willingness to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria for bereaved families were being relatives of the deceased, who were seeking to discharge the body of the deceased person within the mentioned period. For both groups, the exclusion criterion was the lack of answers to 20% of the questions on the questionnaire. A census sampling method was used for selecting medical staff bereaved families. After approval from the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences and obtaining permission from the hospitals, the researcher visited the hospitals for sampling.

The data collection tools included a demographic checklist and two researcher-made questionnaires to examine the needs and problems of the bereaved people from the perspectives of medical staff and bereaved families. The demographic checklist surveyed information about the deceased person (gender, marital status, cause of death), the families of the deceased person (gender, marital status, relationship with the deceased), and the medical staff (age, gender, marital status, educational level, type of employment, and serving place). The questionnaire that surveys the needs and problems of the bereaved people from the perspective of medical staff has 29 items, and the questionnaire that surveys the perspectives of bereaved families has 26 items, both based on a Likert scale from 1 (absolutely agree) to 4 (absolutely disagree). Both questionnaires measure needs and problems in three areas of welfare, support, and communication. In the questionnaire surveying the perspectives of medical staff, items 1, 2, 16 are the communication domain, items 3,7,8,9, 17,18, 19, 26, 27, and 29 for the support domain, and items 4,5,6,10,11-15,20,21-25, and 28 for the welfare domain. In the questionnaire surveying the bereaved families’ perspectives, items 2-8 and 15 are for the communication domain, items 1,9, 20,21,23,25, and 26 for the support domain, and items 10-19,22, and 24 for the welfare domain. A lower score indicates greater needs and problems. Finally, both groups also answered two open-ended questions to measure their satisfaction.

The validity of the questionnaires was assessed qualitatively and quantitatively based on the opinions of 11 faculty members of the Nasibeh School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, and corrections were applied based on their comments. A content validity index (CVI) of 0.88 and content validity ratio (CVR) of 0.72 was reported the questionnaire surveying the perspectives of medical staff. For the questionnaire surveying the perspectives of bereaved families, CVI=0.93 and CVR=0.74. The Cronbach’s α for the two questionnaires was found to be 0.86 and 0.90, respectively.

Before distributing the questionnaire, the study objectives and methods were explained to the participants, and their informed consent was obtained. Depending on the conditions of the bereaved families, the questionnaires were completed sequentially or intermittently. For the medical staff, the questionnaires were delivered to the head nurse or unit manager. Then, the researcher visited the units to collect the completed questionnaires. The collected data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 22 using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, descriptive statistics (frequency, Percentage, Mean±SD), Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Spearman’s correlation test.

Results

Participants included 257 medical staff and 102 bereaved families. The majority of the deceased people were male and married (52.9%), and the most common cause of their death was disease (76.5%). Most of the bereaved family members were male (58.8%), married (74.5%), and the deceased individuals’ children (82.4%). The medical staff were in the age range of 23-55 years (Mean±SD, 33.94±7.71 years); 80.9% (n=208) were female, 75.1% (n=198) were married, 84.8% had a bachelor’s degree (n=218), and 36.2% (n=93) had permanent employment (Table 1).

The needs and problems from the perspective of medical staff

About 73% of medical staff perceived the presence of the patient’s first-degree relatives at the end of life stage as necessary, while 80% stated that the presence of a chaplain at the end of life can provide emotional comfort to the relatives. More than 90% stated that the existence of a separate unit in the hospital for decedent affairs can be helpful for both the families and the medical staff. More than 90% believed that informing the families about the patient’s death is a difficult task for them and that they do it out of compulsion. Also, 94% perceived it necessary to have a liaison officer in the hospital to inform the families about the patient’s death. More than 97% stated that the presence of all bereaved relatives in the ward can bother other patients. Furthermore, 80% stated that the presence of only one first-degree relative when transferring the deceased person from the ward to the mortuary is sufficient, and when there is no companion, the medical staff can better perform the tasks related to the deceased person. Moreover, 98% stated that seeing the bereaved people upon entering the hospital makes them uncomfortable, and 92% recommended the presence of a gathering hall in the hospital to avoid seeing heartbreaking scenes when starting to work. Also, most medical staff opposed the idea that referring the deceased to the morgue could cause severe dissatisfaction among grieving relatives (Table 2).

Based on two open-ended questions, from the perspective of medical staff, the obvious needs and problems of the bereaved families included the bereaved families’ lack of awareness of the services provided to the patient, lack of timely informing the families about of the patient’s dying conditions, absence of a social worker after the patient’s death, observation of the resuscitation stages and the patient’s death by the families, delay in visiting doctors to write a summary of the case and issue a death certificate (delay in issuing a burial permit), along with the grief of losing a loved one and the heavy medical costs.

The mean score of the questionnaire surveying the perspective of the medical staff was 62.24±7.4, ranging 42-79. The highest agreement rate was related to the communication domain, followed by the welfare and support domains, and the highest disagreement rate was related to the support domain, followed by communication and welfare domains (Table 3).

In examining the difference in the mean scores of this questionnaire based on the demographic characteristics of medical staff, the results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed a statistically significant difference between males and females (P=0.009). However, based on the Kruskal-Wallis test results, no statistically significant difference was observed based on marital status (P=0.848), education level (P=0.294), or type of employment P=0.011 (Table 1). Also, based on the Spearman correlation test, there was a statistically significant relationship between the factors of age (r=-0.308, P<0.001) and work experience (r=-0.332, P<0.001) and the questionnaire score.

The needs and problems from the perspective of bereaved families

More than 90% of bereaved families stated that they needed to be with their patient in the ward during his/her end-of-life moments. More than 90% agreed that there is a need for a separate unit in the hospital to deal with the affairs of the deceased person and that this unit should support them to assess their mental and emotional state. About 97% agreed that if the families do not have enough money at the time of discharge, they should accept the deceased person’s ID card and discharge him/her. About 94% reported the need to receive transportation services at the discharge unit (Table 4).

The mean score of the questionnaire surveying the perspective of bereaved families was 66.04±6.97, ranging 52-86. The highest agreement rate was related to the support domain, followed by communication and welfare dimensions, while the highest disagreement rate was related to the welfare domain, followed by communication and support domains (Table 5).

In examining the difference in the mean scores of this questionnaire based on the demographic characteristics of bereaved families, the results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed no statistically significant difference between males and females (P=0.126). Based on the Kruskal-Wallis test, there was no statistically significant difference based on the marital status (P=0.176), occupation (P=0.355), or relationship with the deceased person (P=0.640). However, this difference was statistically significant in terms of education level (P=0.026) (Table 1). Based on the Spearman correlation test, age had no statistically significant relationship with the questionnaire score (P=1.000).

Discussion

Based on the results of the present study, the perceptions of bereaved families and medical staff regarding the needs and problems of bereaved families in the hospital were almost similar and at an moderate level, indicating the bereaved families’ challenges in dealing with the deceased person’s affairs and they need supportive measures and targeted interventions from the relevant authorities to address their needs and problems. A statistically significant difference was found in the perceptions of families based on educational level; people with a higher level of education have a greater ability to recognize and express the needs and problems of bereaved families due to greater access to information resources, better coping skills, or a deeper psychological understanding of the grieving process. Also, a statistically significant difference was reported in the perceptions of medical staff based on age, work experience, and gender, which indicates the effect of these factors (age, work experience, and gender). Older and experienced medical staff, due to higher knowledge and experience, previous experience of dealing with the bereaved families, and higher skills in dealing with psychological issues, have a deeper perception of grief and achieve a better understanding of the needs of the grieving families. Differences in perspectives of medical staff based on gender can be due to different reactions, perceptions, and characteristics of men and women.

In the present study, we assessed the perception of both groups of bereaved families and medical staff regarding the needs and problems of bereaved families in three dimensions of welfare, support, and communication. According to the results of the present study, the need for a separate unit in the hospital to deal with the affairs of the deceased person, the need for a bereavement room in the hospital for bereaved relatives that provides catering services, and the need for transportation services for bereaved relatives in the discharge unit were among the needs perceived by bereaved families which were related to the welfare dimension. Wandering and wasting time to access an ambulance to transport the deceased person, to discharge the deceased person from the discharge unit, to perform payment checkouts in the Payment Counter, and to discharge the deceased person from the morgue were among the problems perceived by bereaved families, which were also related to the welfare dimension. Therefore, the prolonged process of settlement and delivering the deceased person’s body creates additional psychological pressure on families.

The medical staff mentioned the presence of the patient’s first-degree relatives in the end-of-life stage, the presence of a chaplain to provide emotional comfort to the families, the existence of a separate unit in the hospital (unit of decedent affairs), and the presence of a gathering hall in the hospital to avoid seeing the heartbreaking scenes, as the needs of the bereaved families which were related to the welfare dimension. The medical staff also mentioned the time-consuming process of the discharge of the deceased from the ward (due to delays in visiting doctors to write a summary of the case and issue a death certificate, delays in issuing a burial permit, and referring the deceased to the Forensic Medicine Organization), time-consuming process of payments for the discharge of the deceased from the discharge unit, financial and economic problems of families for the discharge of the deceased person, the lack of a bereavement room in the hospital with catering facilities, and the problems of families for finding an ambulance as the most important problems of the bereaved families which were also related to the welfare dimension.

Gray et al. [9], in a survey of bereaved families, categorized the results of the study into three areas: patient needs (maintaining health, appropriate medication prescription, adherence to patient wishes, physical presence in the patient’s final hours of life, and spiritual and religious end-of-life care), family and caregiver needs (enhanced communication with the patient’s care team, assistance with administrative challenges after death, emotional support, respect and valuing the patient’s life), and organizational facilities and characteristics (optimal staff care team coordination, presence of non-clinical staff for care, optimization of catering services, equipment and facilities for people with disabilities, provision of high-quality food), most of which are consistent with the results of the present study. Giorgali [14] in a study on the needs of bereaved families for bereavement services after the death of a child with cancer in Greece, stated that continuity of bereavement care from the care team, availability, individual care, an interdisciplinary approach, and contact with other bereaved parents were the key elements for providing bereavement services. In Boven et al.’s study [7], the provision of in-hospital bereavement services was also described as a caring behavior and challenge, and bereaved relatives appreciated all the services provided during bereavement. However, service providers, while recognizing the importance of bereavement care, stated that the provision of this care was challenged by several factors, such as insufficient training and time constraints. The results of Kruse et al.’s study [15] on supporting bereaved family members in the loss of children or adolescents also showed that grief counseling should be considered an essential component of health care for bereaved family members, because from the participants’ perspective, this counseling led to their comfort, adaptation, and faster return to daily life. The results of these studies are consistent with some of the results of the present study. Policymakers in Iran should be able to adopt policies using the experiences of the medical team for the bereaved families and take effective measures to provide welfare facilities, counseling services, and administrative and financial assistance to the bereaved families.

Among the needs and problems perceived by the bereaved families related to the support dimension, the need to be present in the ward during the patient’s last hours of life, the failure to transfer the deceased person to the morgue, the need for the Unit of Decedent Affairs to support them and assess their mental and psychological states, the need for a chaplain to be present in the hospital to provide mental and psychological support to the bereaved families, the need for a social worker to be present after the patient’s death, and acceptance of a valid ID card if the families did not have enough money to discharge the deceased person. In the present study, most of bereaved families stated that they had full support by medical staff in terms of performing procedures and they did not delay the time of discharge from the ward. The medical staff’s perceptions related to the support domain included: Families’ ability to meet the deceased person in the ward, the presence of a guide during the discharge of the deceased from the hospital, the presence of only one first-degree relative during the transfer of the deceased from the ward to the morgue, the unwillingness of the bereaved families to transfer the deceased person’s body from the ward to the morgue, as well as the observation of the resuscitation stages and the patient’s death by the patient companions.

In line with these results, several studies have indicated the need for emotional support for bereaved families. Thaqi et al. [16] showed that bereaved family members were satisfied with the patient’s end-of-life care. Information about the grief process and grief-related services was considered useful from their perspective. Researchers believe that the family should be considered as a unit to provide the opportunity for togetherness, mutual reflection, meaningful relationships, preparation for death, and resilience. Ito et al. [17] reported that the support and care needs of service providers such as lack of privacy due to poor design of the emergency department and presence during resuscitation, chaotic environment, and psychosocial reaction in grief, were the challenges in providing support and care to bereaved families, which indicates that emergency nurses need to better understand the experience of bereaved families. In the study by Kalocsai et al. [13] in Canada, nurses and physicians supported the provision of empathetic services to bereaved families. Emotional support is a vital type of support that clinicians are usually unable to provide to bereaved families due to having multiple tasks and responsibilities. Also, the results of Ó Coimín et al. [11] in Ireland showed that, although the quality of care provided by nurses, doctors, and other staff to bereaved families was highly rated, care in areas such as communication, emotional, and spiritual support still needed to be improved. Naef et al. [8] stated that there are many barriers to bereavement care in hospitals, and more research is needed to better understand the barriers and facilitators in the provision of bereavement care. They stated that a need-based guideline to the provision of bereavement care in hospitals is necessary to include the best practices and organizational support required. Also, according to the results of Aoun et al. [18] in Australia, a large gap is observed between the care services provided and the existing guidelines, which indicates that more research is needed in the field of underlying attitudes and patterns of bereavement support. In addition to developing guidelines, positive attitudes of service providers towards these guidelines and the participation of beneficiaries in sharing their experiences in the field of quality service provision are needed to modify the existing guidelines.

Regarding the communication dimension, most of the bereaved families agreed with the appropriateness of the treatment of the medical staff, the way of informing the patient’s death, and the way of transferring the deceased person from the ward to the morgue. The medical staff mentioned the difficulty of informing the families about the patient’s death and the need for a liaison officer in the hospital to inform the families about the patient’s death as the problems and needs related to the communication dimension. Haugen et al. [12] examined the perspectives of bereaved families in seven European and South American countries, and the results showed that there were many services available to provide care to dying patients, but there was still a need to improve skills in dealing with bereaved relatives. This suggests that communication challenges are not unique to a specific country; medical staff in all countries, even in those with advanced health systems, need to improve their communication with bereaved families. According to Aoun et al. [18], providing timely services and establishing effective communication play a crucial role in building trust in the services and focusing on the specific needs of bereaved families, rather than their general needs. In the study by Ito et al. [17], providing insufficient information and inappropriate transmission of bad news by medical staff were one of the care challenges raised by bereaved families. Most of the issues raised in these studies were also reported in the present study. However, there are some discrepancies that can be attributed to ethnic-cultural differences and varying family expectations across different cultures. For example, in the study by Ito et al. [17]only the experiences of bereaved people in the emergency departments were surveyed, where the conditions and emergency services, the anxiety of patient companions, and the lack of psychological preparation to accept bad news are different, which can be considered negative experiences for bereaved families. Overall, bereavement-related problems are a significant health issue, but there is lack of economic resources and investment for effective implementation of integrated bereavement care services at national levels [19]. Individual, family, and community-related indicators should be aligned with traditional medical indicators, respecting local cultures and contexts, to ensure that care systems are not only equitable but also responsive to diverse needs [20].

The limitations of this study included a small sample size and the risk of response bias due to the use of self-report tools, and the poor mental conditions of bereaved families and medical staff, which may affect their response to the questions. We offer the following policy recommendations based on the results of the present study:

I) Develop and implement comprehensive guidelines for caring for bereaved families and monitor their implementation:

1) focus on counseling and supportive services; 2) Provide information clearly that is understandable to the bereaved families, taking into account legal requirements and confidentiality of their information; 3) determine the level of family caregivers’ involvement in the end-of-life stage; 4) provide adequate information on the limitations of palliative care; 5) support according to the needs of bereaved families in a safe and ethical manner.

II) specialized communication training for medical staff, especially in the field of bereavement care:

1) issues related to grief should be included in the educational programs of medical staff; 2) necessary training should be provided to all medical staff on how to inform the bereaved families about bad news; 3) by improving appropriate communication between the doctor and the patient’s companions, timely information about the condition of the critically ill patient should be provided in an understandable and clear language.

III. Improving the welfare facilities in the hospital:

1) A quiet place with appropriate welfare facilities should be provided in the hospital for bereavement and the gathering of bereaved families; 2) the method of providing information and access to transportation and ambulance services for the transfer of the deceased person should be clarified in coordination with the relevant units.

IV. Facilitating administrative and financial processes related to the discharge of deceased people.

V. Establish specialized units and interdisciplinary teams for end-of-life care and bereaved families:

1) A team to deal with the affairs of deceased people, led by a trained person, should be established in the hospital to reduce the problems of the bereaved families; 2) trained personnel should be assigned to resolve the issues related to deceased individuals and carry out administrative procedures to achieve greater satisfaction with the provision of hospital services.

Pay special attention to spiritual and cultural support:

1) conditions for access to a chaplain should be provided to comfort the dying person and the bereaved families based on their religious beliefs and cultures; 2) medical staff should be aware of the cultural and spiritual sensitivities to death and bereavement, and facilities should be provided in the hospital to implement spiritual and religious programs. Designing interventions to respect the human aspect of care: An effort should be made to include issues related to grief and support for bereaved families in the educational and cultural programs of medical staff.

Conclusion

The results of the present study indicate that the problems and needs of bereaved families in hospitals are multidimensional. It is necessary to pay attention to the welfare, support, and communication dimensions of these problems and needs for bereaved families. Ethnic, cultural, and environmental differences, as well as individual differences, should be considered in the design of comprehensive interventions, as these differences have a significant impact on supporting bereaved families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1394.H102). Verbal consent was obtained from the participants. They were assured that their information would be kept confidential. All ethical principles were considered in the present study.

Funding

This study was part of the result of a research project approved and financially supported by Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: 2-94).

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences and all families and the medical staff of selected hospitals in Sari who participated in this study for their cooperation.

References

- Lai WS, Li WW, Chiu WH. Grieving in silence: Experiences of bereaved Taiwanese family members whose loved ones died from cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021; 52:101967. [PMID]

- Majid U, Akande A. Managing anticipatory grief in family and partners: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Fam J. 2022; 30(2):242-9. [DOI:10.1177/10664807211000715]

- Meichsner F, O'Connor M, Skritskaya N, Shear MK. Grief before and after bereavement in the elderly: An approach to care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020; 28(5):560-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.12.010] [PMID]

- Sanderson EAM, Humphreys S, Walker F, Harris D, Carduff E, McPeake J, et al. Risk factors for complicated grief among family members bereaved in intensive care unit settings: A systematic review. Plos One. 2022; 17(3):e0264971. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0264971] [PMID]

- Kustanti CY, Chu H, Kang XL, Huang TW, Jen HJ, Liu D, et al. Prevalence of grief disorders in bereaved families of cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2022; 36(2):305-18. [DOI:10.1177/02692163211066747] [PMID]

- Mason TM, Tofthagen CS, Buck HG. Complicated grief: Risk factors, protective factors, and interventions. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2020; 16(2):151-74. [DOI:10.1080/15524256.2020.1745726] [PMID]

- Boven C, Dillen L, Van den Block L, Piers R, Van Den Noortgate N, Van Humbeeck L. In-hospital bereavement services as an act of care and a challenge: An integrative review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022; 63(3):e295-316. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.10.008] [PMID]

- Naef R, Peng-Keller S, Rettke H, Rufer M, Petry H. Hospital-based bereavement care provision: A cross-sectional survey with health professionals. Palliat Med. 2020; 34(4):547-52. [DOI:10.1177/0269216319891070] [PMID]

- Gray C, Yefimova M, McCaa M, Goebel JR, Shreve S, Lorenz KA, et al. Developing unique insights from narrative responses to bereaved family surveys. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020; 60(4):699-708. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.007] [PMID]

- Downar J, Sinuff T, Kalocsai C, Przybylak-Brouillard A, Smith O, Cook D, et al. A qualitative study of bereaved family members with complicated grief following a death in the intensive care unit. Can J Anaesth. 2020; 67(6):685-93. [DOI:10.1007/s12630-020-01573-z] [PMID]

- Ó Coimín D, Prizeman G, Korn B, Donnelly S, Hynes G. Dying in acute hospitals: Voices of bereaved relatives. BMC Palliat Care. 2019; 18(1):91. [DOI:10.1186/s12904-019-0464-z] [PMID]

- Haugen DF, Hufthammer KO, Gerlach C, Sigurdardottir K, Hansen MIT, Ting G, et al. Good quality care for cancer patients dying in hospitals, but Information Needs Unmet: Bereaved relatives' survey within seven countries. Oncologist. 2021; 26(7):e1273-84. [DOI:10.1002/onco.13837] [PMID]

- Kalocsai C, des Ordons AR, Sinuff T, Koo E, Smith O, Cook D, et al. Critical care providers' support of families in bereavement: A mixed-methods study. Can J Anaesth. 2020; 67(7):857-65. [DOI:10.1007/s12630-020-01645-0] [PMID]

- Giorgali S. Bereaved parents' needs regarding hospital based bereavement care after the death of a child to cancer. Death Stud. 2022; 46(6):1472-80. [DOI:10.1080/07481187.2020.1824202] [PMID]

- Kruse RF, Stiel S, Schwabe S. Supporting bereaved family members: A qualitative interview study on the experience of bereavement counselling by the bereavement network lower saxony (BNLS) in Germany for parents who have lost children or teenagers. Omega. 2024; 302228241263367. [DOI:10.1177/00302228241263367] [PMID]

- Thaqi Q, Riguzzi M, Blum D, Peng-Keller S, Lorch A, Naef R. End-of-life and bereavement support to families in cancer care: A cross-sectional survey with bereaved family members. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024; 24(1):155. [DOI:10.1186/s12913-024-10575-2] [PMID]

- Ito Y, Tsubaki M, Kobayashi M. Families' experiences of grief and bereavement in the emergency department: A scoping review. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2022; 19(1):e12451. [DOI:10.1111/jjns.12451] [PMID]

- Aoun SM, Rumbold B, Howting D, Bolleter A, Breen LJ. Bereavement support for family caregivers: The gap between guidelines and practice in palliative care. Plos One. 2017; 12(10):e0184750. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0184750] [PMID]

- Lichtenthal WG, Roberts KE, Donovan LA, Breen LJ, Aoun SM, Connor SR, Rosa WE. Investing in bereavement care as a public health priority. Lancet Public Health. 2024; 9(4):e270-4. [DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00030-6] [PMID]

- Ntizimira CR, Dunne M, Rana S, Birindabagabo P. End-of-life care needs decolonising. BMJ. 2024; 387:q2810. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.q2810] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2025/04/24 | Accepted: 2025/09/19 | Published: 2025/09/19

Received: 2025/04/24 | Accepted: 2025/09/19 | Published: 2025/09/19

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |