Fri, Jan 30, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 2, Issue 4 (Summer 2024)

CPR 2024, 2(4): 233-240 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.ATU.REC.1401.009

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Anvari A, Kazemian S, Khodadadi Sangdeh J. The Role of Family Interactions in Pain Perception Among Patients With Psychogenic Pain Complaints. CPR 2024; 2 (4) :233-240

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-133-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-133-en.html

Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 587 kb]

(145 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (513 Views)

Full-Text: (84 Views)

Introduction

Some pains have psychological origins due to the complex relationship between emotional and physical health [1]. Psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, and depression can manifest as physical symptoms, leading to pain complaints [2]. This occurs because the brain processes emotional distress, which can trigger physiological responses, including muscle tension and altered pain perception [3]. Consequently, individuals may experience pain without any identifiable physical symptoms [4]. Pain with psychological symptoms is often called psychogenic or somatoform pain, which manifests without a known cause but is felt by patients. This phenomenon highlights the complex relationship between the mind and body, where psychological processes can influence physiological functioning and pain perception [5]. Understanding pain complaints is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies that address both the mental and physical dimensions of the individual’s health [6].

Family interactions can significantly influence pain complaints through emotional support and communication patterns. Positive family dynamics, characterized by open communication and emotional support, can help individuals cope with stress and emotional distress, potentially alleviating psychosomatic symptoms [7]. Conversely, dysfunctional family relationships may exacerbate feelings of isolation, anxiety, or depression, which can intensify the experience of pain [8]. The quality of family interactions thus plays a crucial role in shaping an individual’s emotional landscape and, consequently, their experience of pain [9]. Moreover, family members often serve as primary caregivers, and their responses to a patient’s pain can affect the patient’s psychological well-being. Supportive family members who acknowledge and validate their patients’ pain can foster a sense of safety and understanding, which may mitigate the psychological factors contributing to pain complaints [10]. In contrast, dismissive or critical responses from family members can lead to increased emotional distress, reinforcing the pain experience. Therefore, the nature of family interactions can either buffer or amplify the psychological stressors associated with psychosomatic conditions [11]. Family interactions can also influence coping strategies employed by individuals with pain complaints. Families that encourage adaptive coping strategies, such as problem-solving and emotional expression, can help individuals manage their pain more effectively [12]. On the other hand, families that promote maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance or denial, may hinder an individual’s ability to confront and process their emotional distress, potentially worsening their psychosomatic symptoms [13].

Despite growing recognition of the biopsychosocial dimensions of pain, few studies have systematically explored how family interactions shape the subjective experience of pain, particularly in non-clinical populations. This gap underscores the need for an in-depth, context-sensitive investigation of family dynamics, employing qualitative thematic analysis to capture nuanced narratives and uncover latent patterns in interpersonal processes. By examining these interactions through patients’ lived experiences, this study explores how family support or family conflicts influence psychogenic pain perception. The purpose is to identify the role of family interactions in psychogenic pain perception among Iranian patients with pain complaints. Findings can help design family-centered interventions that target not only pain management but also the psychological distress embedded in relational contexts, ultimately advancing holistic care frameworks.

Materials and Methods

This is a qualitative study using the thematic content analysis method. The study population included all individuals experiencing pain complaints aged 20-40 residing in Tehran, Iran, in 2023. As the study required participants with specific characteristics, a purposive sampling method was adopted to select the participants. Participants were invited through virtual social networks. The inclusion criteria were: Experiencing pain, a score above 31 on Takata and Sakata’s psychosomatic complaints scale [14] to find individuals with clinically significant somatic symptoms (among whom pain complaints are highly prevalent), age 20-40 years, residency in Tehran, and willingness to participate in the study. The psychosomatic complaints scale measures a broader range of psychosomatic complaints (e.g. fatigue, dizziness, gastrointestinal issues) beyond pain. A total of 80 individuals completed the questionnaire, among whom 51 scored above 31, indicating the presence of pain complaints.

Those with pain complaints who volunteered to participate in the study underwent semi-structured interviews online. The interviews were conducted individually on one of the online messaging platforms. Interviews were conducted until reaching data saturation, which was reached after 16 interviews. We performed two more interviews to ensure theoretical sufficiency. Each interview lasted about 45-60 minutes. Prior to the interview, the research objectives were explained to the participants, the confidentiality of their information was assured, and their informed consent for recording the interviews was obtained. Each interview began with general questions related to the research topic and phenomenon, specifically about the impact of family relationships before the onset of pain complaints. One key question was as follows: “Can you describe a specific situation where your family members’ behaviors significantly affected your experience of pain, positively or negatively?”. This question elicited concrete examples of how family interactions modulated pain perception, revealing both supportive and conflictual family dynamics. These general questions were followed by probe questions to explore further and reveal the phenomenon, such as “Could you elaborate on how that family interaction made you feel?” or “What happened after that?”. These probes encouraged detailed descriptions of how family dynamics influenced their experiences of pain. Throughout the interview process, the participants’ experiences were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

By examining the participants’ responses, key themes and important points were extracted. Subsequently, the data were analyzed using the Colaizzi method. To ensure the credibility of the data, participant feedback was employed. During the interviews, immediate feedback was provided to confirm the accuracy of the information and to implement necessary adjustments. Additionally, after analyzing each interview, participants were consulted regarding the validity of their statements, leading to confirmations or adjustments as required. To enhance the integrity of the process and improve the overall quality of the research, the data analysis and the assigned codes were presented to the experts and a qualitative research specialist for review.

Results

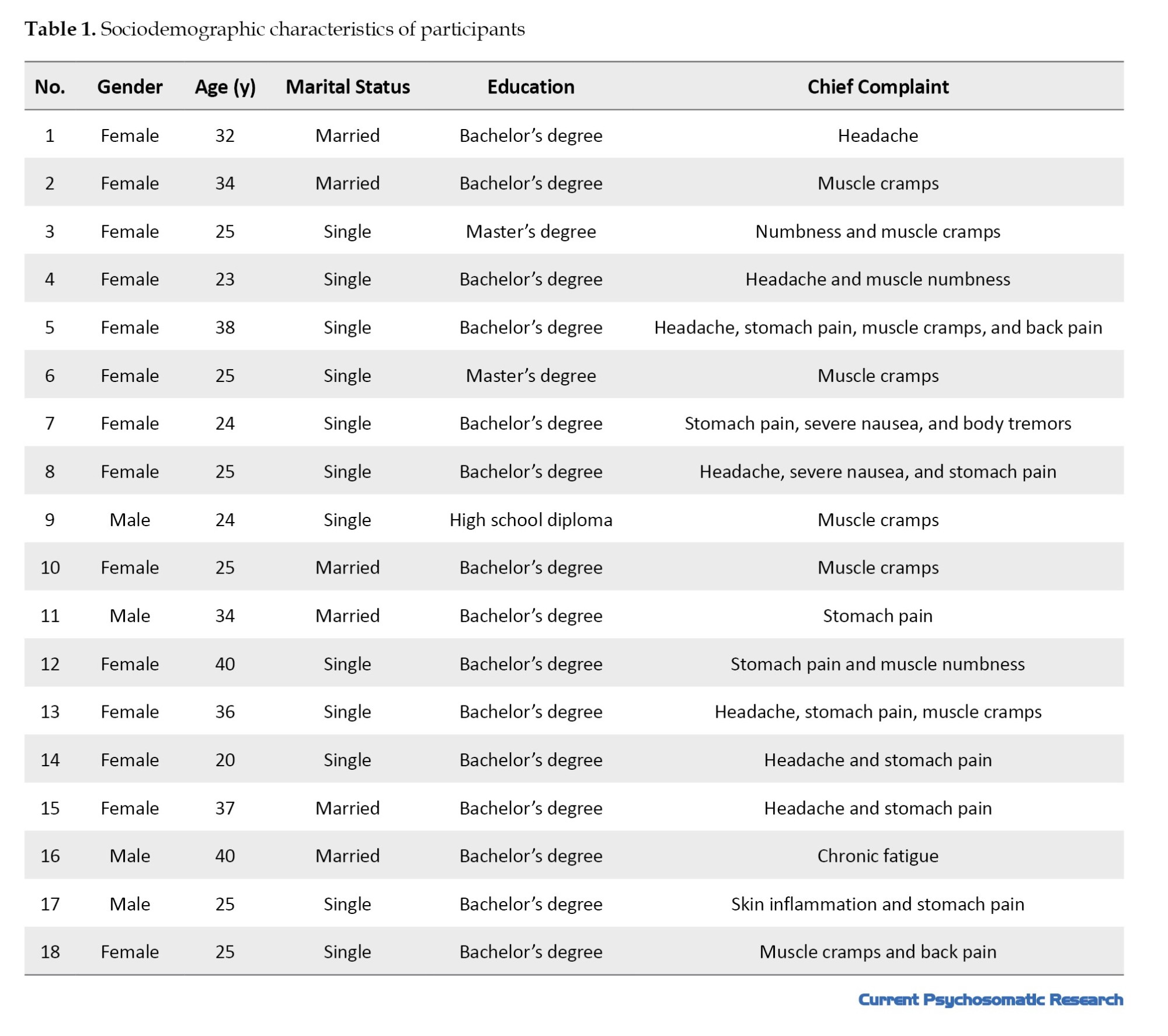

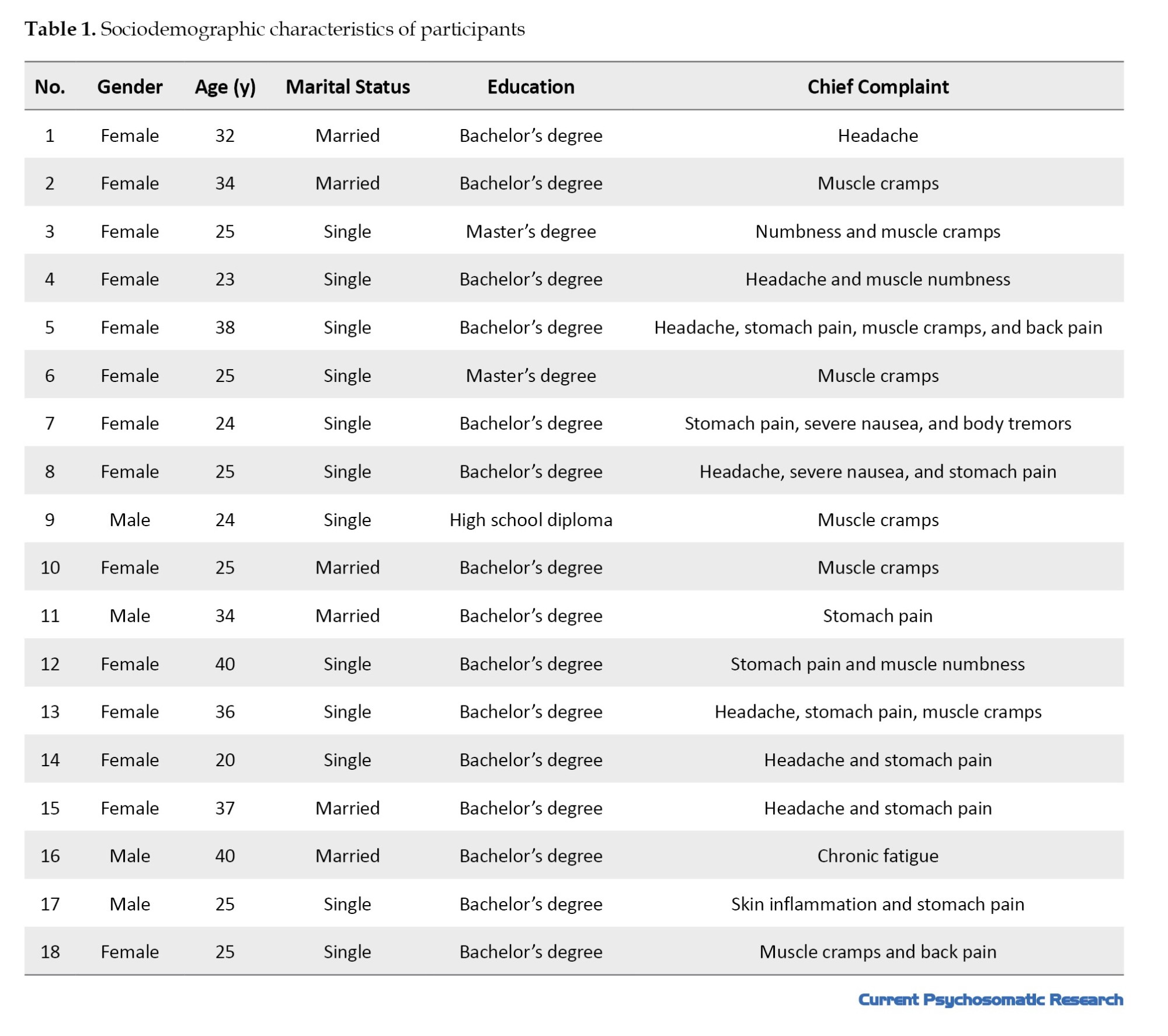

In this study, 18 individuals with pain complaints participated. Their sociodemographic information is presented in Table 1.

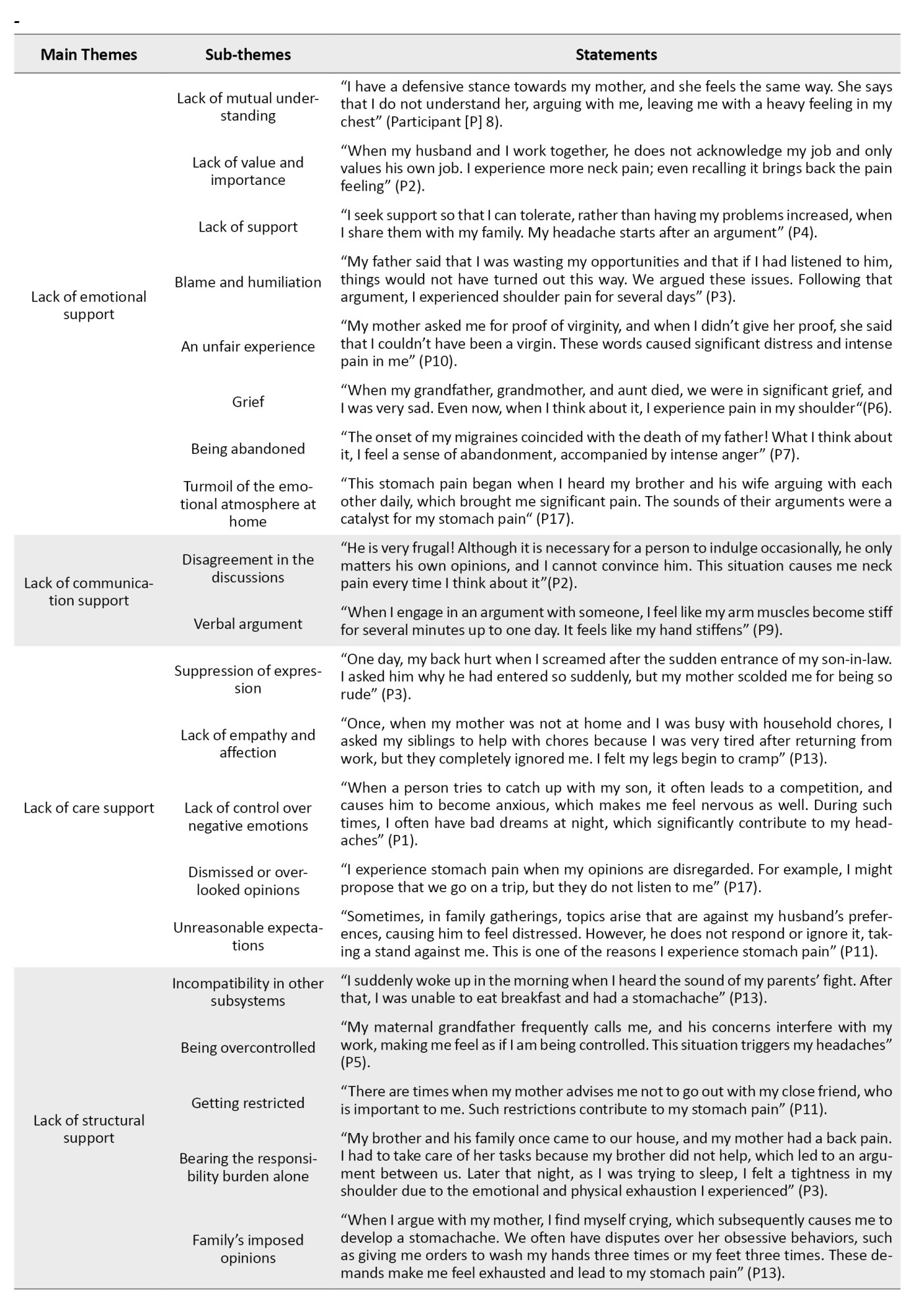

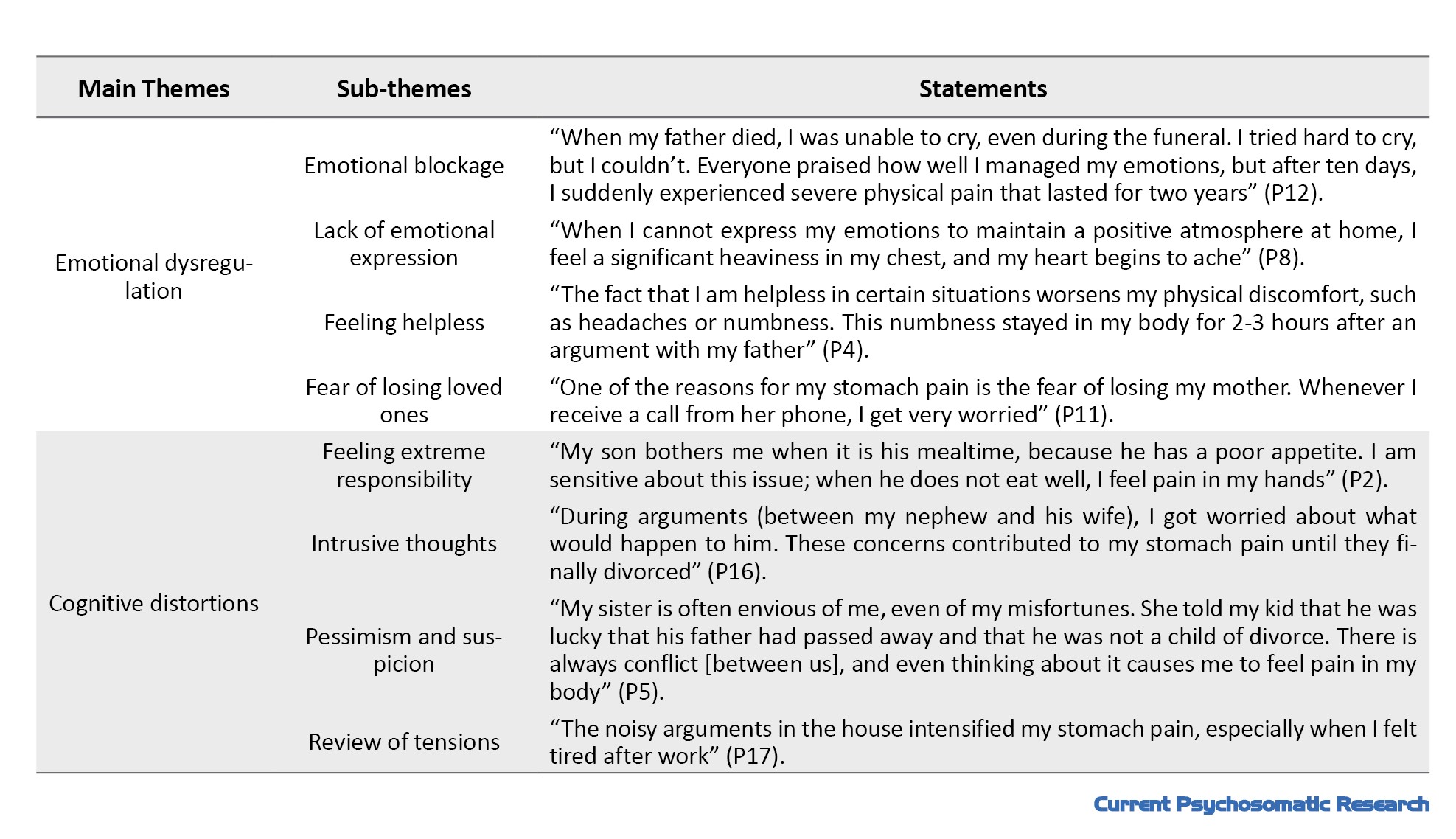

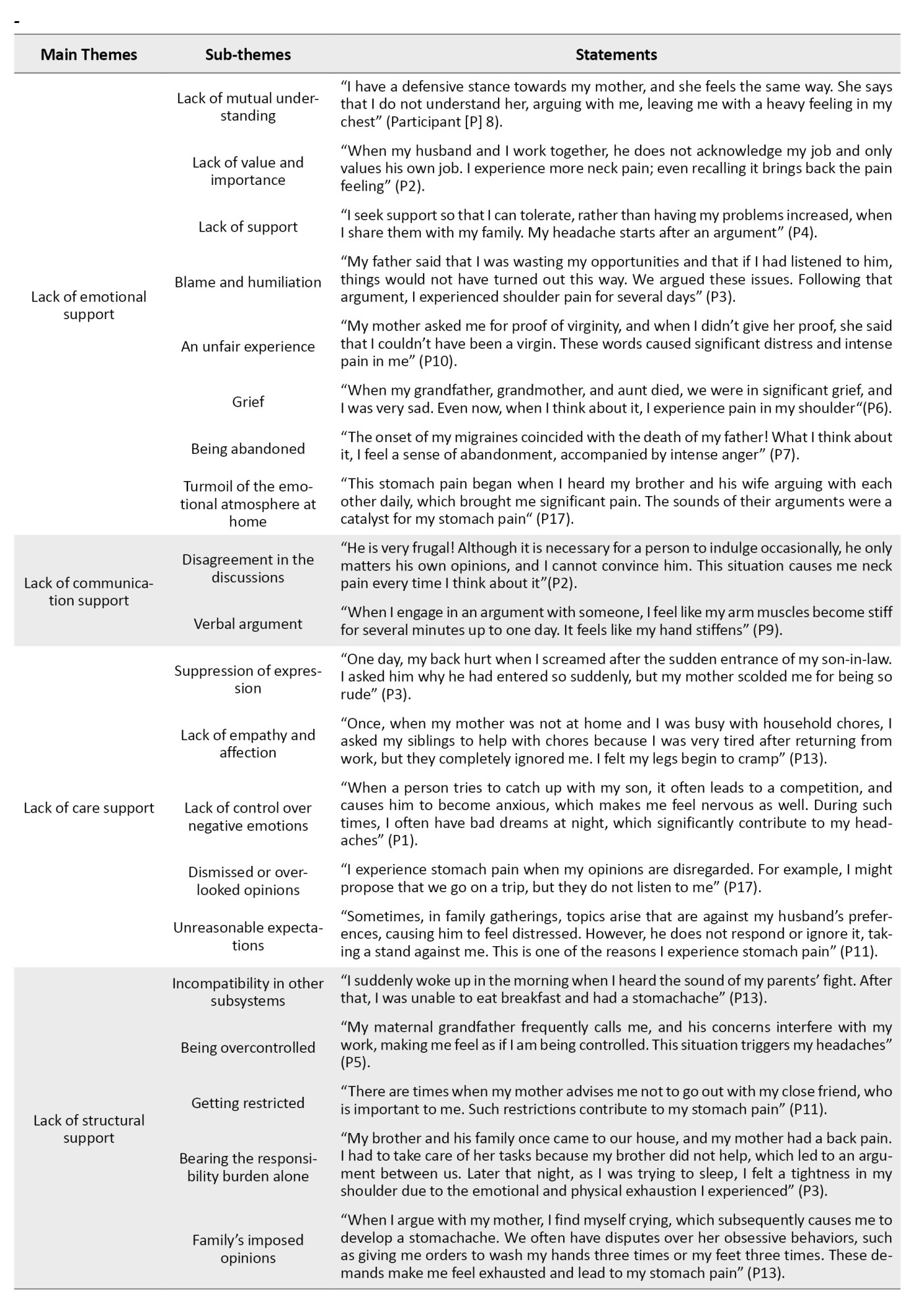

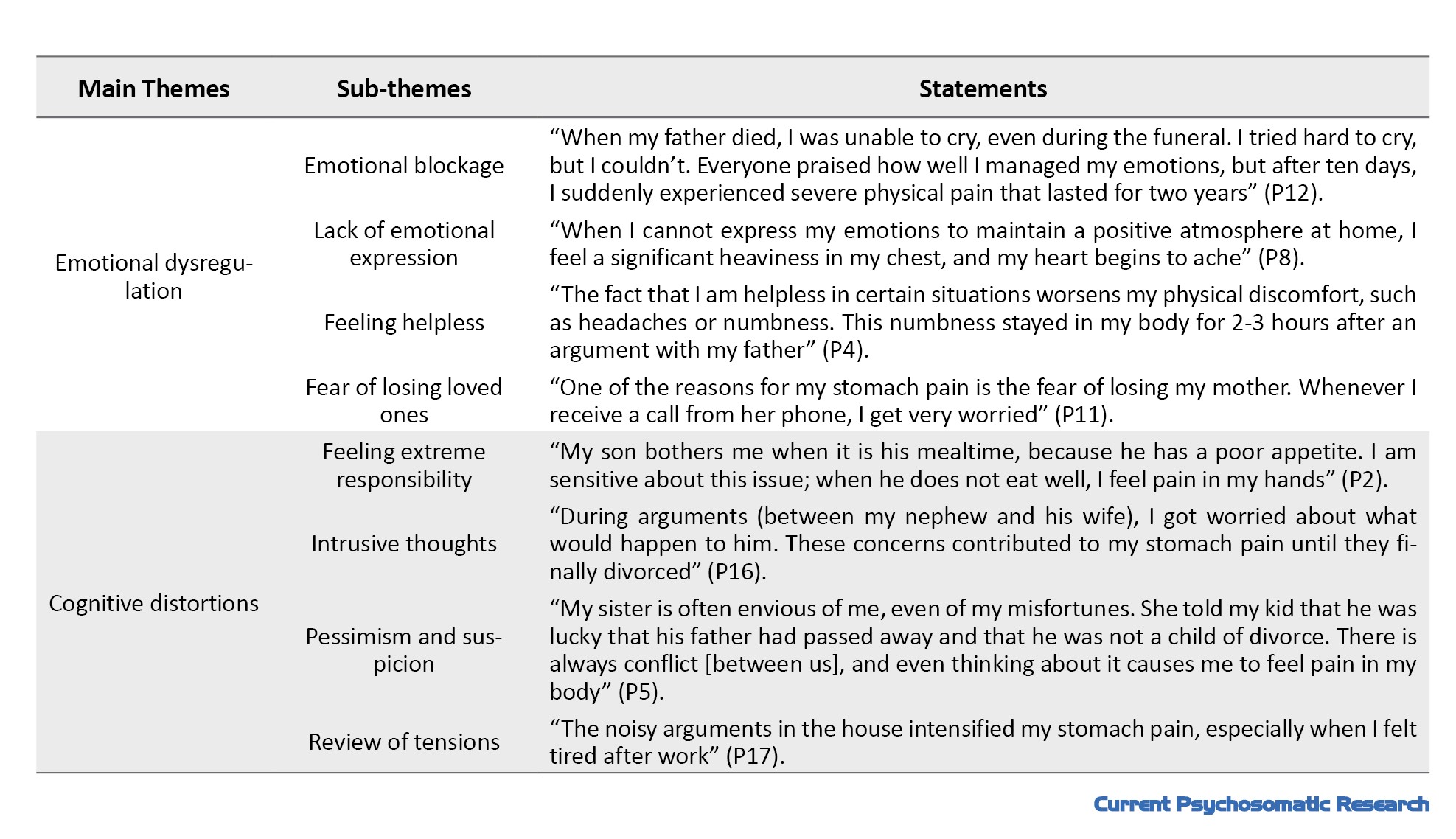

Based on the analysis of interviews, a total of 177 statements, six main themes, and 28 sub-themes were identified (Table 2).

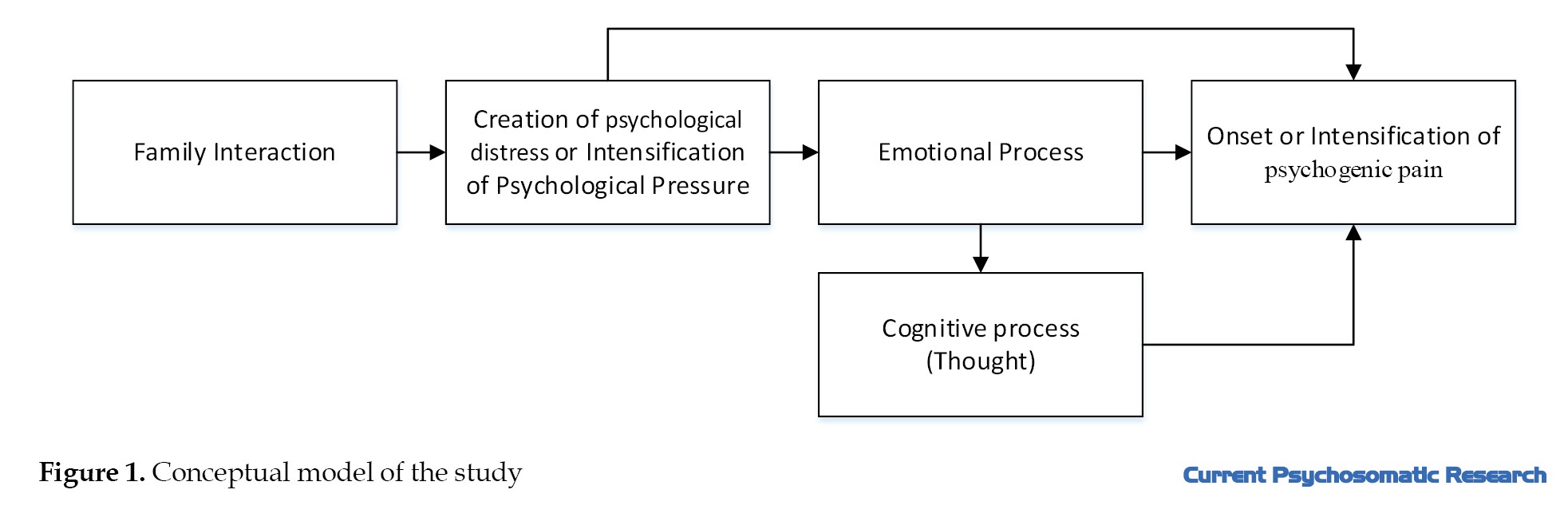

Based on the themes identified and the role of psychological distress as a connecting factor between family interactions and psychogenic pain, it can be said that the identified themes of family interactions influence psychogenic pain complaints in two ways: Directly (family interactions lead to the onset or exacerbation of psychogenic pain) and Indirectly (family interactions initiate or intensify psychogenic pain through an intrapsychic process). Figure 1 illustrates these relationships.

Discussion

The purpose of the present research was to identify the role of family interactions in the psychogenic pain perception of individuals. The results showed that the lack of emotional support from the family can lead to the onset or exacerbation of pain complaints. This is consistent with the results of Manavipour and Miri [15]. Emotional support deficiencies within the family can significantly exacerbate pain complaints in individuals with psychosomatic complaints [16]. When family members fail to show understanding, empathy, and encouragement, individuals with pain complaints may feel isolated and misunderstood, leading to increased pain. This emotional support neglect can exacerbate psychogenic symptoms, as the mind and body are interconnected [17]. The lack of a supportive network can hinder coping mechanisms, making it difficult for individuals to manage their pain effectively. Consequently, it may perpetuate a cycle of distress, where unresolved psychological issues manifest as intensified physical discomfort.

Another finding of the study was that the lack of communication support from the family can initiate or exacerbate pain complaints in individuals with psychogenic pain. Rahavi and Baghianimoghadam [18] and Rahimi and Khayyer [19], consistent with the findings of our study, showed that communication problems in the family environment, such as verbal conflicts and tensions, have an impact on pain complaints. When family members struggle to express their feelings or misunderstand each other, it creates confusion and frustration. The lack of effective communication can lead to unresolved conflicts and heightened emotional distress, which may manifest as physical symptoms [20]. Individuals may feel unsupported or ignored, which can intensify their psychosomatic pain. Moreover, poor communication can hinder the ability to seek help or share coping strategies, further exacerbating their pain and creating a cycle of suffering that intertwines emotional and physical health.

This study demonstrated that the lack of structural support from the family can exacerbate pain complaints in individuals with psychogenic pain. Laghi et al. [21] also indicated the role of structural support in pain complaints. When families lack resources, stability, or clear roles, individuals with pain complaints may experience increased anxiety and uncertainty about their conditions. This instability can lead to feelings of helplessness and inadequacy, which may exacerbate existing physical symptoms [22]. Moreover, without a structured support system, individuals may struggle to access necessary care or use effective coping strategies, making it difficult to manage their pain effectively [23]. The absence of reliable support can create a sense of isolation, further intensifying the connection between emotional distress and physical discomfort, ultimately perpetuating the cycle of psychosomatic pain.

Our study revealed that deficiencies in emotion regulation can lead to the exacerbation of psychogenic pain complaints. Studies by Allahverdi [24] and Myles and Merlo [25] yielded results similar to those of the present study. When individuals struggle to manage their emotions effectively, they may experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety, which can manifest as physical pain [26]. Ineffective emotion regulation often leads to the suppression of feelings, resulting in the bottling up of emotions that creates tension in the body. This accumulated distress can exacerbate existing physical symptoms, making them feel more intense. Furthermore, individuals who cannot express or process their emotions may resort to maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance or denial, which can further increase their pain experience [27]. Ultimately, the interplay between unregulated emotions and physical discomfort creates a vicious cycle, where emotional distress exacerbates pain complaints, complicating the individual’s overall well-being.

Finally, the results of this study indicated that cognitive distortions can affect psychogenic pain complaints. These findings are consistent with the results of Dimitrova [28] and Behzadi and Rahmati [29]. When individuals experience cognitive distortions, such as catastrophizing or negative thinking, they may exaggerate their perception of pain and discomfort. These cognitive distortions can lead to increased anxiety and fear about their symptoms, which can heighten their physical experience of pain [30]. Additionally, it may hinder effective coping strategies, making it challenging for individuals to manage their symptoms [31]. The cognitive overload can create a feedback loop where negative thoughts and heightened pain feed into each other, ultimately intensifying the psychosomatic pain and complicating the individual’s overall health.

One of the limitations of the present study was that many eligible men were unwilling to participate, and those who did often struggled to express their emotions and experiences. As a result, most of the findings are confined to the experiences of women. Another limitation was the inability to eliminate interviewer bias during the interviews and data analysis. Given the constraints of qualitative research, tracking changes in family interaction processes related to pain complaints was not feasible. Based on the results of this study, it is recommended that psychologists and counselors focus on family interactions and utilize family therapy approaches to address pain complaints effectively.

Conclusion

Six main themes of family interactions and 28 sub-themes were extracted. The themes included: lack of emotional support, lack of communication support, lack of care support, lack of structural support, emotional dysregulation, and cognitive distortions. It seems that various aspects of family support (emotional, communicative, care, and structural), and family-related emotional and cognitive problems can influence the onset or exacerbation of pain in patients with psychogenic pain complaints. Addressing these factors may be effective in developing interventional programs for those with pain complaints.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.ATU.REC.1401.009). All participants declared their informed consent after receiving general explanations about the research objectives. They were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This study was extracted from a master’s thesis of Afagh Anvari, approved by the Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

Some pains have psychological origins due to the complex relationship between emotional and physical health [1]. Psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, and depression can manifest as physical symptoms, leading to pain complaints [2]. This occurs because the brain processes emotional distress, which can trigger physiological responses, including muscle tension and altered pain perception [3]. Consequently, individuals may experience pain without any identifiable physical symptoms [4]. Pain with psychological symptoms is often called psychogenic or somatoform pain, which manifests without a known cause but is felt by patients. This phenomenon highlights the complex relationship between the mind and body, where psychological processes can influence physiological functioning and pain perception [5]. Understanding pain complaints is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies that address both the mental and physical dimensions of the individual’s health [6].

Family interactions can significantly influence pain complaints through emotional support and communication patterns. Positive family dynamics, characterized by open communication and emotional support, can help individuals cope with stress and emotional distress, potentially alleviating psychosomatic symptoms [7]. Conversely, dysfunctional family relationships may exacerbate feelings of isolation, anxiety, or depression, which can intensify the experience of pain [8]. The quality of family interactions thus plays a crucial role in shaping an individual’s emotional landscape and, consequently, their experience of pain [9]. Moreover, family members often serve as primary caregivers, and their responses to a patient’s pain can affect the patient’s psychological well-being. Supportive family members who acknowledge and validate their patients’ pain can foster a sense of safety and understanding, which may mitigate the psychological factors contributing to pain complaints [10]. In contrast, dismissive or critical responses from family members can lead to increased emotional distress, reinforcing the pain experience. Therefore, the nature of family interactions can either buffer or amplify the psychological stressors associated with psychosomatic conditions [11]. Family interactions can also influence coping strategies employed by individuals with pain complaints. Families that encourage adaptive coping strategies, such as problem-solving and emotional expression, can help individuals manage their pain more effectively [12]. On the other hand, families that promote maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance or denial, may hinder an individual’s ability to confront and process their emotional distress, potentially worsening their psychosomatic symptoms [13].

Despite growing recognition of the biopsychosocial dimensions of pain, few studies have systematically explored how family interactions shape the subjective experience of pain, particularly in non-clinical populations. This gap underscores the need for an in-depth, context-sensitive investigation of family dynamics, employing qualitative thematic analysis to capture nuanced narratives and uncover latent patterns in interpersonal processes. By examining these interactions through patients’ lived experiences, this study explores how family support or family conflicts influence psychogenic pain perception. The purpose is to identify the role of family interactions in psychogenic pain perception among Iranian patients with pain complaints. Findings can help design family-centered interventions that target not only pain management but also the psychological distress embedded in relational contexts, ultimately advancing holistic care frameworks.

Materials and Methods

This is a qualitative study using the thematic content analysis method. The study population included all individuals experiencing pain complaints aged 20-40 residing in Tehran, Iran, in 2023. As the study required participants with specific characteristics, a purposive sampling method was adopted to select the participants. Participants were invited through virtual social networks. The inclusion criteria were: Experiencing pain, a score above 31 on Takata and Sakata’s psychosomatic complaints scale [14] to find individuals with clinically significant somatic symptoms (among whom pain complaints are highly prevalent), age 20-40 years, residency in Tehran, and willingness to participate in the study. The psychosomatic complaints scale measures a broader range of psychosomatic complaints (e.g. fatigue, dizziness, gastrointestinal issues) beyond pain. A total of 80 individuals completed the questionnaire, among whom 51 scored above 31, indicating the presence of pain complaints.

Those with pain complaints who volunteered to participate in the study underwent semi-structured interviews online. The interviews were conducted individually on one of the online messaging platforms. Interviews were conducted until reaching data saturation, which was reached after 16 interviews. We performed two more interviews to ensure theoretical sufficiency. Each interview lasted about 45-60 minutes. Prior to the interview, the research objectives were explained to the participants, the confidentiality of their information was assured, and their informed consent for recording the interviews was obtained. Each interview began with general questions related to the research topic and phenomenon, specifically about the impact of family relationships before the onset of pain complaints. One key question was as follows: “Can you describe a specific situation where your family members’ behaviors significantly affected your experience of pain, positively or negatively?”. This question elicited concrete examples of how family interactions modulated pain perception, revealing both supportive and conflictual family dynamics. These general questions were followed by probe questions to explore further and reveal the phenomenon, such as “Could you elaborate on how that family interaction made you feel?” or “What happened after that?”. These probes encouraged detailed descriptions of how family dynamics influenced their experiences of pain. Throughout the interview process, the participants’ experiences were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

By examining the participants’ responses, key themes and important points were extracted. Subsequently, the data were analyzed using the Colaizzi method. To ensure the credibility of the data, participant feedback was employed. During the interviews, immediate feedback was provided to confirm the accuracy of the information and to implement necessary adjustments. Additionally, after analyzing each interview, participants were consulted regarding the validity of their statements, leading to confirmations or adjustments as required. To enhance the integrity of the process and improve the overall quality of the research, the data analysis and the assigned codes were presented to the experts and a qualitative research specialist for review.

Results

In this study, 18 individuals with pain complaints participated. Their sociodemographic information is presented in Table 1.

Based on the analysis of interviews, a total of 177 statements, six main themes, and 28 sub-themes were identified (Table 2).

Based on the themes identified and the role of psychological distress as a connecting factor between family interactions and psychogenic pain, it can be said that the identified themes of family interactions influence psychogenic pain complaints in two ways: Directly (family interactions lead to the onset or exacerbation of psychogenic pain) and Indirectly (family interactions initiate or intensify psychogenic pain through an intrapsychic process). Figure 1 illustrates these relationships.

Discussion

The purpose of the present research was to identify the role of family interactions in the psychogenic pain perception of individuals. The results showed that the lack of emotional support from the family can lead to the onset or exacerbation of pain complaints. This is consistent with the results of Manavipour and Miri [15]. Emotional support deficiencies within the family can significantly exacerbate pain complaints in individuals with psychosomatic complaints [16]. When family members fail to show understanding, empathy, and encouragement, individuals with pain complaints may feel isolated and misunderstood, leading to increased pain. This emotional support neglect can exacerbate psychogenic symptoms, as the mind and body are interconnected [17]. The lack of a supportive network can hinder coping mechanisms, making it difficult for individuals to manage their pain effectively. Consequently, it may perpetuate a cycle of distress, where unresolved psychological issues manifest as intensified physical discomfort.

Another finding of the study was that the lack of communication support from the family can initiate or exacerbate pain complaints in individuals with psychogenic pain. Rahavi and Baghianimoghadam [18] and Rahimi and Khayyer [19], consistent with the findings of our study, showed that communication problems in the family environment, such as verbal conflicts and tensions, have an impact on pain complaints. When family members struggle to express their feelings or misunderstand each other, it creates confusion and frustration. The lack of effective communication can lead to unresolved conflicts and heightened emotional distress, which may manifest as physical symptoms [20]. Individuals may feel unsupported or ignored, which can intensify their psychosomatic pain. Moreover, poor communication can hinder the ability to seek help or share coping strategies, further exacerbating their pain and creating a cycle of suffering that intertwines emotional and physical health.

This study demonstrated that the lack of structural support from the family can exacerbate pain complaints in individuals with psychogenic pain. Laghi et al. [21] also indicated the role of structural support in pain complaints. When families lack resources, stability, or clear roles, individuals with pain complaints may experience increased anxiety and uncertainty about their conditions. This instability can lead to feelings of helplessness and inadequacy, which may exacerbate existing physical symptoms [22]. Moreover, without a structured support system, individuals may struggle to access necessary care or use effective coping strategies, making it difficult to manage their pain effectively [23]. The absence of reliable support can create a sense of isolation, further intensifying the connection between emotional distress and physical discomfort, ultimately perpetuating the cycle of psychosomatic pain.

Our study revealed that deficiencies in emotion regulation can lead to the exacerbation of psychogenic pain complaints. Studies by Allahverdi [24] and Myles and Merlo [25] yielded results similar to those of the present study. When individuals struggle to manage their emotions effectively, they may experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety, which can manifest as physical pain [26]. Ineffective emotion regulation often leads to the suppression of feelings, resulting in the bottling up of emotions that creates tension in the body. This accumulated distress can exacerbate existing physical symptoms, making them feel more intense. Furthermore, individuals who cannot express or process their emotions may resort to maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance or denial, which can further increase their pain experience [27]. Ultimately, the interplay between unregulated emotions and physical discomfort creates a vicious cycle, where emotional distress exacerbates pain complaints, complicating the individual’s overall well-being.

Finally, the results of this study indicated that cognitive distortions can affect psychogenic pain complaints. These findings are consistent with the results of Dimitrova [28] and Behzadi and Rahmati [29]. When individuals experience cognitive distortions, such as catastrophizing or negative thinking, they may exaggerate their perception of pain and discomfort. These cognitive distortions can lead to increased anxiety and fear about their symptoms, which can heighten their physical experience of pain [30]. Additionally, it may hinder effective coping strategies, making it challenging for individuals to manage their symptoms [31]. The cognitive overload can create a feedback loop where negative thoughts and heightened pain feed into each other, ultimately intensifying the psychosomatic pain and complicating the individual’s overall health.

One of the limitations of the present study was that many eligible men were unwilling to participate, and those who did often struggled to express their emotions and experiences. As a result, most of the findings are confined to the experiences of women. Another limitation was the inability to eliminate interviewer bias during the interviews and data analysis. Given the constraints of qualitative research, tracking changes in family interaction processes related to pain complaints was not feasible. Based on the results of this study, it is recommended that psychologists and counselors focus on family interactions and utilize family therapy approaches to address pain complaints effectively.

Conclusion

Six main themes of family interactions and 28 sub-themes were extracted. The themes included: lack of emotional support, lack of communication support, lack of care support, lack of structural support, emotional dysregulation, and cognitive distortions. It seems that various aspects of family support (emotional, communicative, care, and structural), and family-related emotional and cognitive problems can influence the onset or exacerbation of pain in patients with psychogenic pain complaints. Addressing these factors may be effective in developing interventional programs for those with pain complaints.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.ATU.REC.1401.009). All participants declared their informed consent after receiving general explanations about the research objectives. They were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This study was extracted from a master’s thesis of Afagh Anvari, approved by the Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Cozzi G, Lucarelli A, Borrometi F, Corsini I, Passone E, Pusceddu S, et al. How to recognize and manage psychosomatic pain in the pediatric emergency department. Ital J Pediatr. 2021; 47(1):74. [DOI:10.1186/s13052-021-01029-0] [PMID]

- Mijiti A, Huojia M. Psychosomatic problems. Br Dent J. 2020; 228(10):738. [DOI:10.1038/s41415-020-1688-2] [PMID]

- Alfven G, Grillner S, Andersson E. Review of childhood pain highlights the role of negative stress. Acta Paediatr. 2019; 108(12):2148-56. [DOI:10.1111/apa.14884] [PMID]

- Goetzmann L, Siegel A, Ruettner B. The connectivity/conversion paradigm-A new approach to the classification of psychosomatic disorders. N Ideas Psychol. 2019; 52:26-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.08.001]

- Urien L, Wang J. Top-down cortical control of acute and chronic pain. Psychosom Med. 2019; 81(9):851-8. [DOI:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000744] [PMID]

- Rąglewska P, Dembiński J, Straburzyńska-Lupa A. Psychosomatic background of cervical spine pain assessed during the Covid-19 pandemic period. Physiother Rev. 2023; 27(2):31-9. [DOI:10.5114/phr.2023.128859]

- Waring EM. The role of the family in symptom selection and perpetuation in psychosomatic illness. Psychother Psychosom. 1977; 28(1-4):253-9. [DOI:10.1159/000287070] [PMID]

- Goli F, Afshar H, Zamani A, Ebrahimi A, Ferdosi M. The relationship between family medicine and psychosomatic medicine. Int J Body Mind Cult. 2017; 4(2):102-7. [DOI:10.22122/ijbmc.v4i2.99]

- Elliott L, Thompson KA, Fobian AD. A systematic review of somatic symptoms in children with a chronically Ill family member. Psychosom Med. 2020; 82(4):366-76.[DOI:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000799] [PMID]

- Kelly C, Molcho M, Doyle P, Gabhainn SN. Psychosomatic symptoms among schoolchildren. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2010; 22(2):229-35. [DOI:10.1515/IJAMH.2010.22.2.229] [PMID]

- Liakopoulou-Kairis M, Alifieraki T, Protagora D, Korpa T, Kondyli K, Dimosthenous E, et al. Recurrent abdominal pain and headache--psychopathology, life events and family functioning. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002; 11(3):115-22. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-002-0276-0] [PMID]

- Vervoort T, Karos K, Trost Z, Prkachin KM. Social and interpersonal dynamics in pain: We don’t suffer alone. New York: Springer; 2018. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-78340-6]

- Turk DC, Gatchel RJ. Psychological approaches to pain management: A practitioner’s handbook. New York: Guilford publications; 2018. [Link]

- Takata Y, Sakata Y. Development of a psychosomatic complaints scale for adolescents. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004; 58(1):3-7. [DOI:10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00777.x] [PMID]

- Manavipour D, Miri LS. [Early maladaptive schemas in patients with psychosomatic disorder and multiple sclerosis (Persian)]. Neurosci J Shefaye Khatam. 2017; 5(1):40-7. [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.shefa.5.1.40]

- Erriu M, Cimino S, Cerniglia L. The role of family relationships in eating disorders in adolescents: A narrative review. Behav Sci. 2020; 10(4):71. [DOI:10.3390/bs10040071] [PMID]

- Boggero IA, Sturgeon JA, Arewasikporn A, Castro SA, King CD, Segerstrom SC. Associations of pain intensity and frequency with loneliness, hostility, and social functioning: Cross-Sectional, longitudinal, and within-person relationships. Int J Behav Med. 2019; 26(2):217-29. [DOI:10.1007/s12529-019-09776-5] [PMID]

- Rahavi E, Baghianimoghadam M. [The role of the family atmosphere in relation to public health through high school female students in the city of Yazd (Persian)]. Tolooebehdasht. 2015; 14(2):138-48. [Link]

- Rahimi M, Khayyer M. [The relationship between family communication patterns and quality of life in Shiraz high school (Persian)]. Found Educ. 2009; 010(1):1. [DOI:10.22067/fe.v10i1.2096]

- Amato PR, Booth A. The legacy of parents’ marital discord: Consequences for children’s marital quality. J pers Soc Psychol. 2001; 81(4):627-38. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.627]

- Laghi F, McPhie ML, Baumgartner E, Rawana JS, Pompili S, Baiocco R. Family functioning and dysfunctional eating among Italian adolescents: The moderating role of gender. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016; 47(1):43-52. [DOI:10.1007/s10578-015-0543-1] [PMID]

- Mller-Fabian A. Case study of a psychosomatic family. Bull Univ Agricult Sci Vet Med Cluj Napoca Hortic. 2013; 70(2):470. [Link]

- Sefidari L, Mohammadzadeh Ebrahimi A, Hemat Afza P. [The effectiveness of family-structured minochin therapy on chronic anxiety and differentiation in patients with psychosomatic disorders (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi J. 2022; 11(5):221-30. [Link]

- Allahverdi E. Psychosomatic pain. In: Çakmur H, editor. Effects of stress on human health. London: IntechOpen; 2020. [DOI:10.5772/intechopen.91328]

- Myles LAM, Merlo EM. Alexithymia and physical outcomes in psychosomatic subjects: A cross-sectional study. J Mind Med Sci. 2021; 8(1):86-93. [DOI:10.22543/7674.81.P8693]

- Sajjadia I, Taher Neshat Dost H, Molavi H, Bagherian-Sararoudi R. Cognitive and emotional factors effective on chronic low back pain in women: Explanation the role of fear-avoidance believes, pain catastrophizing and anxiety. J Res Behav Sci. 2012; 9(5):305-16. [Link]

- Godin O, Tzourio C, Maillard P, Mazoyer B, Dufouil C. Antihypertensive treatment and change in blood pressure are associated with the progression of white matter lesion volumes: The three-city (3C)-Dijon magnetic resonance imaging study. Circulation. 2011; 123(3):266-73. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.961052] [PMID]

- Dimitrova L. Psychosomatic disorders in adolescents. Knowl Int J. 2020; 38(4):849-51. [Link]

- Behzadi Z, Rahmati S. Prevalence of Obsessive beliefs in Rheumatoid Arthritis patients and compared with healthy peoples. J Res Psychol Health. 2016; 10(1):43-51. [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.rph.10.1.43]

- Sarafraz M, Parsamahjoob M. [The role of emotions regulation, perceived stress, rumination and anxiety in patients with Ischemic heart disease and healthy control (Persian)]. Armaghane Danesh. 2019; 24(2):262-73. [Link]

- Babamiri M, Neisi A, Arshadi N, Mehrabizadeh Honarmand M, Beshlideh K. [Job stressors and personality characteristics as predictors of psychosomatic symptoms of the staff of a company in Ahwaz (Persian)]. Psychol Achiev. 2015; 22(1):187-208. [DOI:10.22055/psy.2015.11198]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Physiotherapy and pain

Received: 2025/01/18 | Accepted: 2025/07/8 | Published: 2025/09/19

Received: 2025/01/18 | Accepted: 2025/07/8 | Published: 2025/09/19

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |