Sat, Feb 21, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 2, Issue 3 (Spring 2024)

CPR 2024, 2(3): 197-204 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Alsadat Razavi F, Salari E, Ebrahimi M E, Sedrpoushan N. Comparing ACT and Reality Therapy for Reducing Anxiety and Improving Career Decision Self-efficacy. CPR 2024; 2 (3) :197-204

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-129-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-129-en.html

Department of Counselling, Faculty of Humanities, Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran.

Keywords: Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), Anxiety, Career path decision-making self-efficacy (CDSE), Reality therapy (RT)

Full-Text [PDF 706 kb]

(433 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1042 Views)

Full-Text: (333 Views)

Introduction

The teenage period is a critical phase in life that shapes personality, career interests, and future job choices [1]. It involves cognitive, biological, social, and emotional changes, with effects that last throughout life [2]. One of the key concerns during adolescence is the transition to adulthood and the ability to make informed career decisions. Career readiness plays a crucial role in long-term professional success; however, many teenagers struggle with low self-efficacy in making career-related choices [3, 4]. Furthermore, adolescent mental health, particularly among female teenagers, is receiving increasing attention due to its impact on academic performance, social relationships, and overall well-being [2]. Various challenges during this period prevent individuals from reaching their full potential, making it crucial to identify these problems and address them early to ensure a healthier society [1]. Given the psychological challenges and external pressures affecting career decision-making during adolescence, enhancing career path decision-making self-efficacy (CDSE) becomes particularly important. As mentioned, these issues can hinder adolescents from realizing their full potential, making improvements in self-efficacy in this area crucial for both career success and mental well-being.

CDSE is one of the main challenges for teenagers, referring to their belief in their ability to handle tasks related to career decision-making [5]. External pressures often prevent individuals from making value-driven decisions [6]. Additionally, mental health factors, such as anxiety, significantly influence decision-making processes and career-related confidence. Psychological flexibility, the ability to cope with anxiety, fear of failure, and hopelessness, is essential for building self-efficacy [7]. Anxiety, a disabling state, affects various areas of life and is one of the most common mental disorders, characterized by emotional, behavioral, and physical symptoms [8, 9].

Several psychological interventions have been developed to address these issues; two well-known therapies for increasing CDSE and reducing anxiety are acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) [10] and reality therapy (RT) [11]. ACT focuses on psychological flexibility, teaching individuals that thoughts and feelings are temporary and do not define reality. By accepting pain and tension, people can make value-driven decisions despite discomfort [12]. ACT therapists aim to help clients become more aware of their thoughts and emotions and make choices based on their values [13]. ACT, which is part of the third wave of behavioral therapies, enhances psychological flexibility through mindful acceptance and value-based planning [14]. Research shows that ACT improves self-efficacy and reduces anxiety, depression, and stress [15].

RT, on the other hand, argues that human behavior is driven by internal needs rather than external conditions [16]. Through choice theory, RT helps individuals make responsible decisions and manage emotions, such as anxiety [17]. RT encourages people to take control of their behavior rather than trying to control others. Its main goal is to help individuals understand their needs and make effective choices [17]. RT emphasizes responsibility and planning as essential human needs, arguing that failure to address them leads to mental health issues, like depression and anxiety [18]. Additionally, RT improves self-efficacy and reduces anxiety [19].

Although both ACT and RT belong to the third wave of behavioral therapies and emphasize values and planning, ACT uses mindfulness techniques and highlights the futility of controlling thoughts and feelings [20], while RT focuses on responsible decision-making without this emphasis. Despite the growing body of literature on ACT and RT, a direct comparison of their effectiveness in addressing CDSE and anxiety among adolescents is lacking. This research gap underscores the need for comparative studies that can clarify their relative impact.

Based on the outlined background, this study aimed to fill this gap by comparing the effectiveness of ACT and RT in addressing CDSE and reducing anxiety among female high school students. Comparing these approaches could provide valuable insights into behavioral therapies.

Based on the outlined background, the objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of ACT and RT in addressing CDSE and reducing anxiety among female high school students. Given the significance of the teenage period in shaping personality, career choices, and mental health, this study aimed to evaluate how these two third-wave behavioral therapies, with their differing emphases on psychological flexibility and responsibility, impact teenagers’ abilities to make informed career decisions and manage anxiety. The findings may provide insights into the relative strengths of ACT and RT in enhancing CDSE and reducing anxiety in adolescents. Additionally, the findings may contribute to a deeper understanding of the strengths and limitations of each approach, guiding future interventions aimed at improving adolescent career readiness and mental well-being.

Materials and Methods

The study population consisted of all female high school students in Yazd who were studying in the 2022-2023 academic year. Using cluster sampling, Region 2 of Yazd was selected, and one school from this region was chosen as the sample. Based on Cohen’s (2013) guidelines [21], a sample size of 12 to 15 participants per group was considered. A total of 45 students were selected through convenience sampling and were then randomly divided into three groups: 15 in the ACT group, 14 in the RT group, and 15 in the control group. Ultimately, one participant from the RT group dropped out. In the next step, the participants responded to the Beck anxiety scale (1988) and CDSE scale by Betz and Taylor (1983) during two stages of the research: Pre-test and post-test [24]. Participants in the intervention group received ACT and RT training in a group format (as training and skill development) for two months, with one session each week, and each session lasting 90 minutes. However, no training was delivered to the control group. Inclusion criteria were being a student at a secondary school, being a girl, residing in Yazd City, having not experienced stressful events in the past six months, and not receiving psychological treatment simultaneously for anxiety disorder. The exclusion criteria were the occurrence of a significant stressful life event, the initiation of psychiatric medication use, and students being absent from the research process for two consecutive sessions or three irregular sessions.

Research tools

Anxiety inventory

This scale was developed by Beck (1988) and consists of 21 items scored using four options. The internal consistency coefficient (α) for this scale was 0.82, indicating good reliability [22]. The validity of the Persian version was tested using the test re-test method with a one-week interval (0.75), and its item correlation varied from 0.30 to 0.76 [23].

CDSE

This 2-item scale was developed by Betz et al. in 1983 [24]. It evaluates five capacities related to career choice based on Crites’s model (1961). For example, this scale includes items, such as 1) Proper self-evaluation, 2) Gathering career information, 3) Choosing a goal, 4) Planning for the future, and 5) Problem-solving. The scale is scored using a four-point scale, ranging from lack of self-confidence to complete self-confidence. Betz et al. (1996) calculated and confirmed its reliability using Cronbach’s α (0.97) [24]. In Iran, the reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s α (0.78) [25].

ACT protocol

This protocol was developed by Hayes in 2004 and consists of eight sessions. It combines four approaches: Awareness, acceptance, commitment, and behavior change. It aims to achieve psychological flexibility, allowing individuals to act based on perceived values despite experiencing negative feelings [10]. The first intervention group was designated as the ACT group.

The ACT sessions followed a structured approach. Participants began with a pre-test, evaluation, and diagnostic interview. The first session introduced ACT concepts and challenged control strategies, followed by training in creative hopelessness and exploring unresolved issues in the second session. The third session focused on fostering acceptance and mindfulness, while the fourth emphasized living and choosing based on values. The fifth and sixth sessions refined participants’ goals, values, and actions, addressing barriers and promoting commitment. The seventh session aimed to remove obstacles to committed actions and concluded with a post-test, and the final session included evaluations and therapy adjustments.

RT protocol

This protocol was developed by Wubbolding in 2017 and consists of “reality,” “responsibility,” and “right and wrong differentiation.” The RT school stated that individuals suffer from human, social, and global situations in addition to mental and physical diseases. Accordingly, the failure of individuals to achieve their basic needs causes their behaviors to deviate from defined norms. Since necessary needs are considered a part of individuals’ lives, RT does not address past problems. Furthermore, the principles of this therapy do not involve the difficulties related to unconscious issues. RT emphasizes problem-solving and focuses on the present situation of the individual. It offers better options for the future of individuals through training. In RT, individuals are guided to understand what they want and how they can behave to achieve their goals effectively [11]. RT training was delivered to the second intervention group based on the Glasser model. The RT sessions began with a briefing to outline regulations, build group communication, administer a pre-test, and share the training plan. The first session introduced group members, objectives, and the history of choice theory. The second session focused on human behavior and the five basic needs, while the third covered internal/external control, as well as the ten principles of choice theory. The fourth session introduced the concepts of the real and ideal worlds, behavior components, and the behavior machine. The fifth session focused on building realistic goals, while the sixth session addressed planning to achieve them. The seventh session covered practical steps using ability cards, and the eighth session emphasized responsibility and concluded with a summary.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the distribution of the dependent variables, and Levene’s test was applied to evaluate the equality of error variance across groups. Additionally, the M-Box test was used to examine the homogeneity of variance-covariance. To analyse the overall effect of the independent variable (treatment method) on the dependent variables, multivariate analyses using criteria, such as Pillai’s trace, Wilks’ lambda, Hotelling’s trace, and Roy’s largest root, were utilized. Furthermore, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to compare the post-test scores between the groups while controlling for pre-test scores. Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to determine pairwise differences. SPSS software, version 23, was used to analyze data at a significance level of P<0.05.

Results

The sample consisted of 44 unmarried female high school students from Yazd City. The mean age of the participants was 16.2±0.87 years, ranging from 15 to 17 years. A one-way ANOVA was used to examine the effect of age across the three groups, and the results indicated that age had no significant impact on the study outcomes.

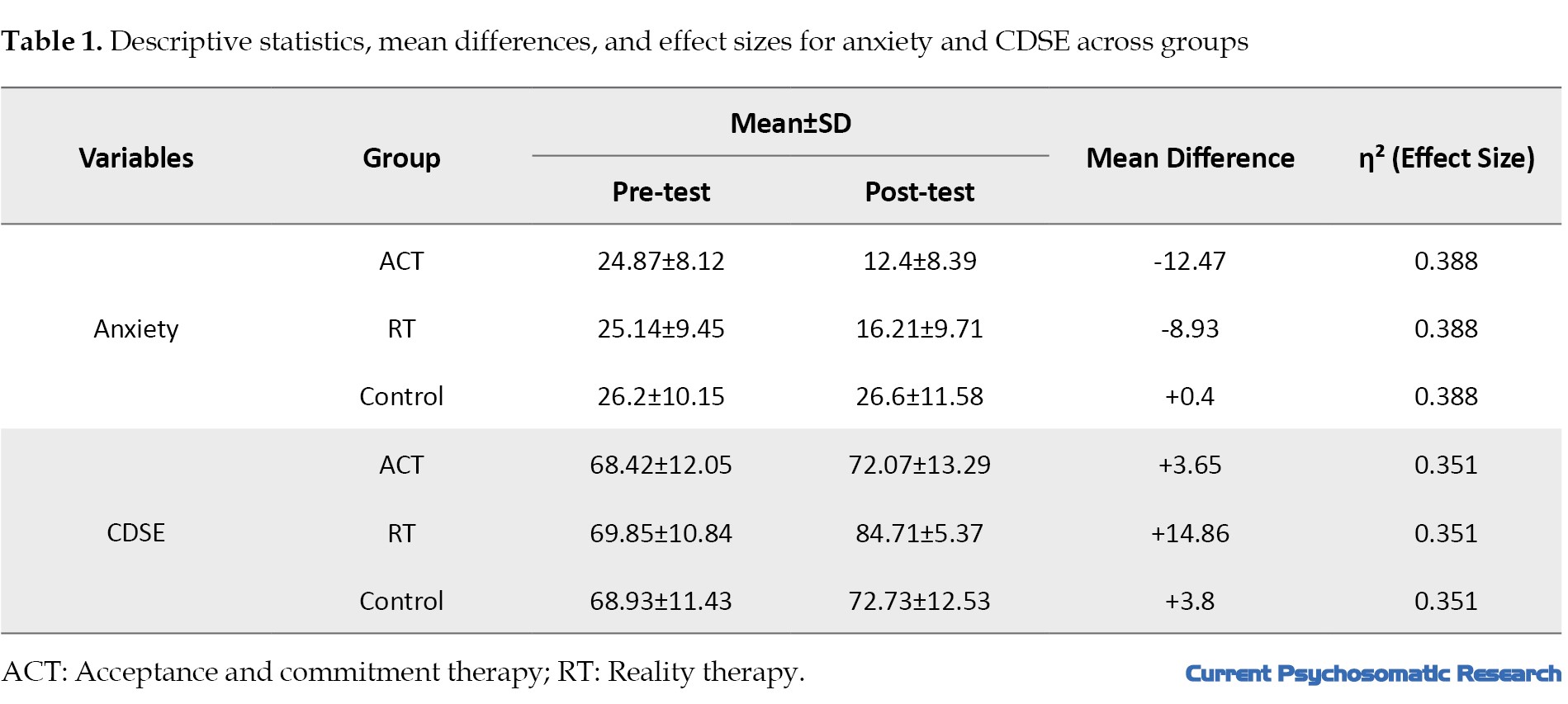

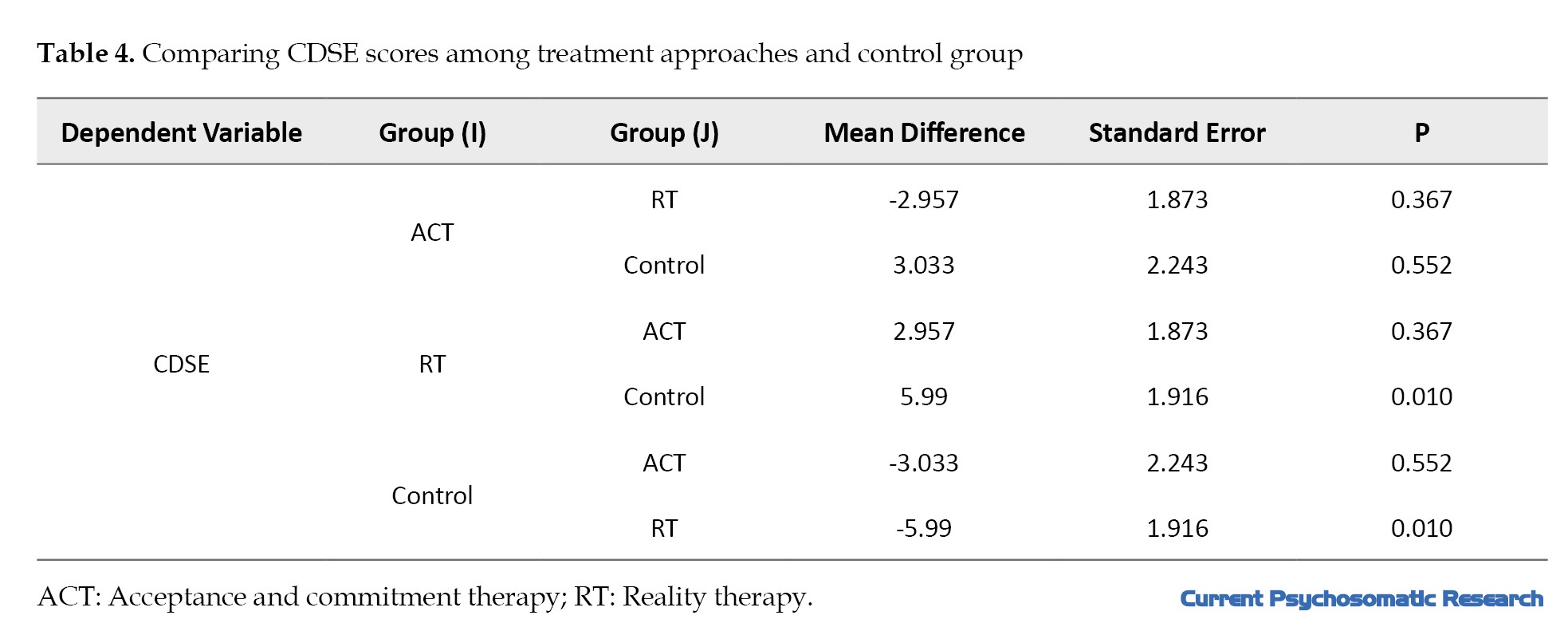

As shown in Table 1, anxiety scores decreased significantly in both the ACT and RT groups, whereas the control group showed no meaningful change.

Regarding CDSE, the RT group demonstrated the highest improvement, while the ACT and control groups showed smaller increases.

To statistically analyze these changes, a repeated measures ANOVA was conducted and the results indicated a significant interaction effect between time (pre-test vs. post-test) and group for both anxiety (F=15.872, P<0.001, η²=0.388) and CDSE (F=12.461, P<0.001, η²=0.351). Bonferroni post-hoc tests confirmed that the ACT and RT groups experienced significant improvements compared to the control group (P<0.01 for all comparisons).

To consider the pre-requisite conditions for parametric analysis, we used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess the normal distribution of dependent variables. The results showed that the anxiety variable did not significantly deviate from normality (P=0.0625), indicating that the normality assumption was not violated. However, for CDSE, the normality assumption was violated (P=0.0165), suggesting that the distribution of CDSE scores significantly deviated from normal. Therefore, parametric analyses could not be conducted for CDSE without further adjustments.

To assess the equality of error variance of the dependent variable across groups, we used the Levene test. The significance levels for both anxiety (P=0.105) and CDSE (P=0.557) were greater than 0.05. Therefore, the assumption of equal error variance was not rejected for either variable, indicating that the groups did not significantly differ in terms of variability.

We used the M-Box test to assess the homogeneity of variances and covariances. The treatment approach had a significant effect on the dependent variables, as indicated by all four multivariate criteria. Pillai’s trace (F=7.291, P=0.000), Wilks’ lambda (F=8.402, P=0.000), Hotelling’s trace (F=9.507, P=0.000), and Roy’s largest root (F=18.998, P=0.000) all yielded significant results with high observed power (ranging from 0.994 to 1). These findings suggest that the combination of the independent variable (treatment approach) significantly impacts the dependent variables, supporting the efficacy of the intervention.

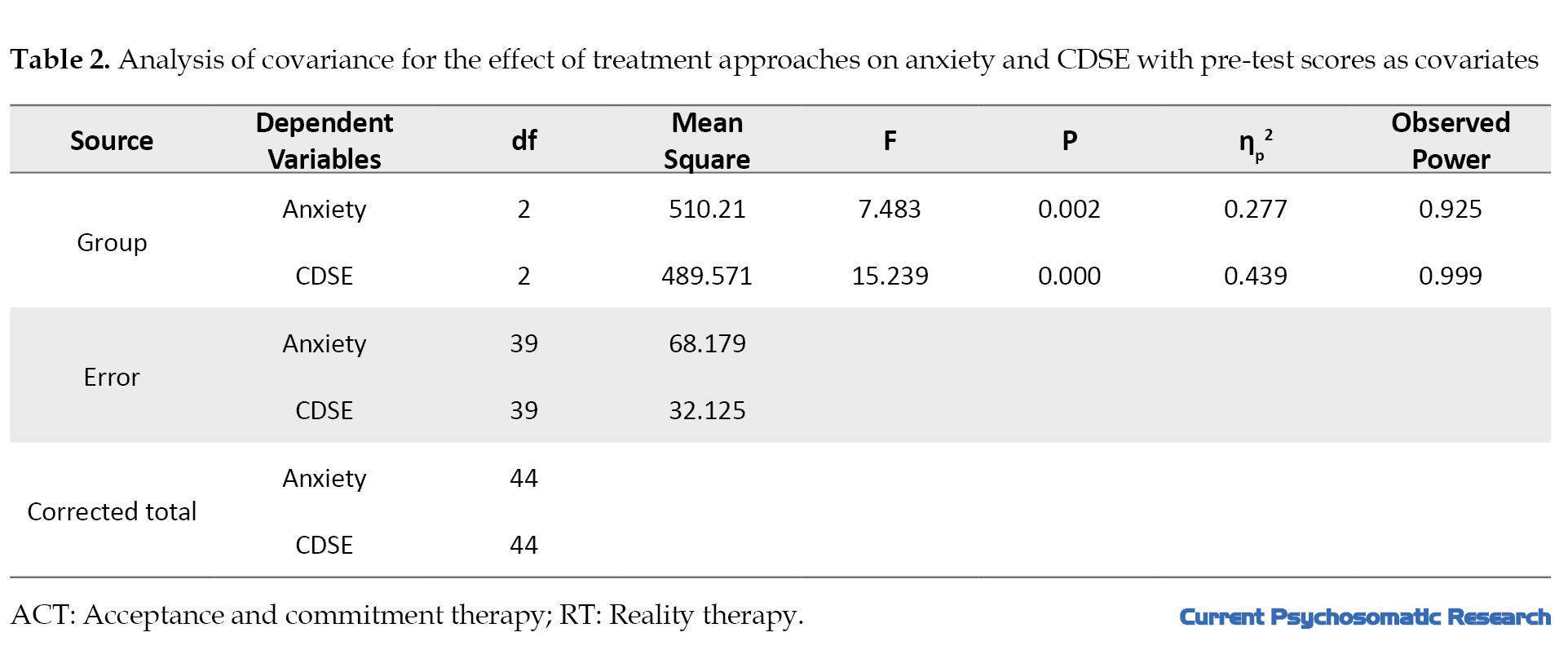

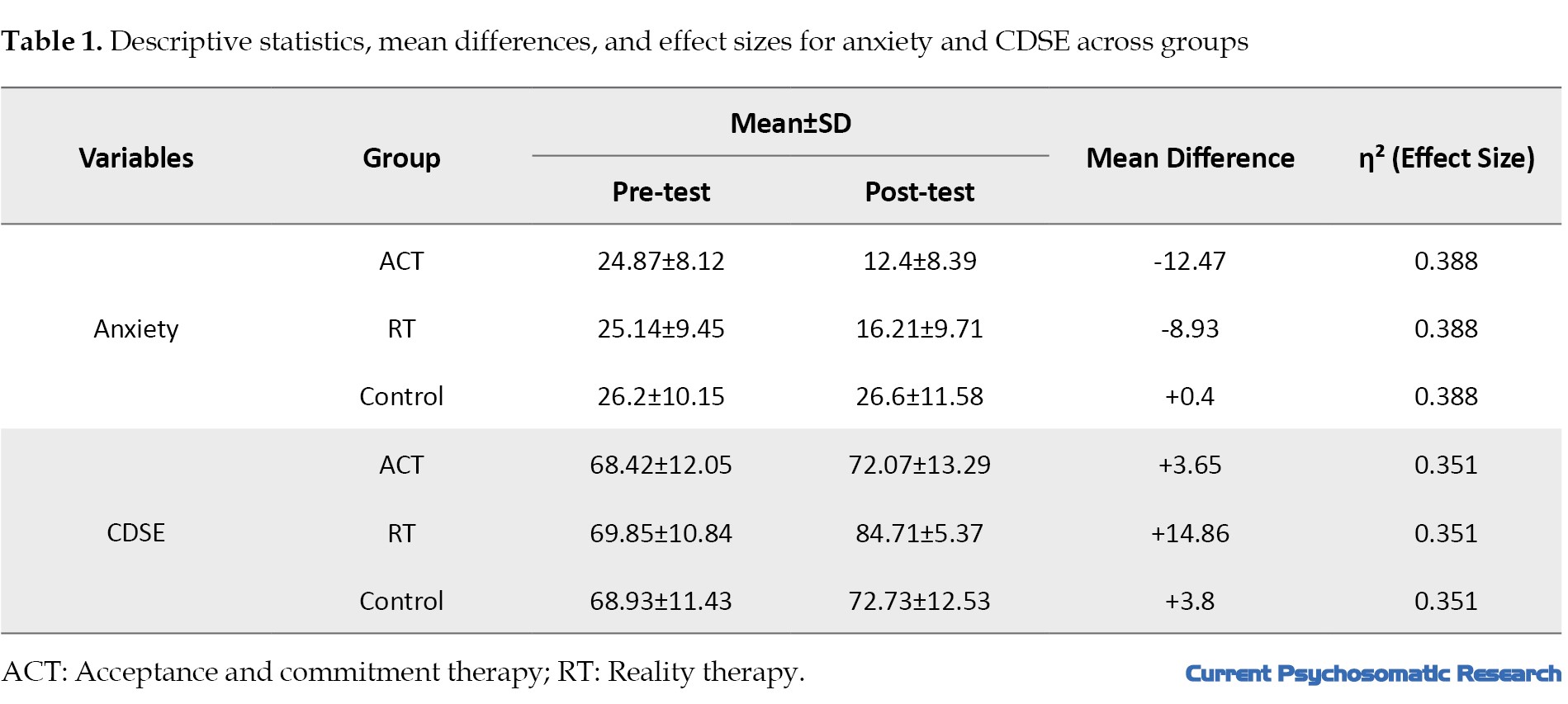

The treatment approaches had a significant effect on both anxiety and CDSE. Specifically, the F-values for anxiety (F=7.483, P=0.002) and CDSE (F=15.239, P=0.000) suggest a significant treatment effect. Additionally, the partial eta squared values of 0.277 for anxiety and 0.439 for CDSE indicated that 27% and 44% of the variance in these variables, respectively, was explained by the type of therapy or treatment approach. The observed power values of 0.925 for anxiety and 0.999 for CDSE indicated a strong statistical power for detecting the effects of the treatments. In the next step, Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to compare the treatment groups (Table 2).

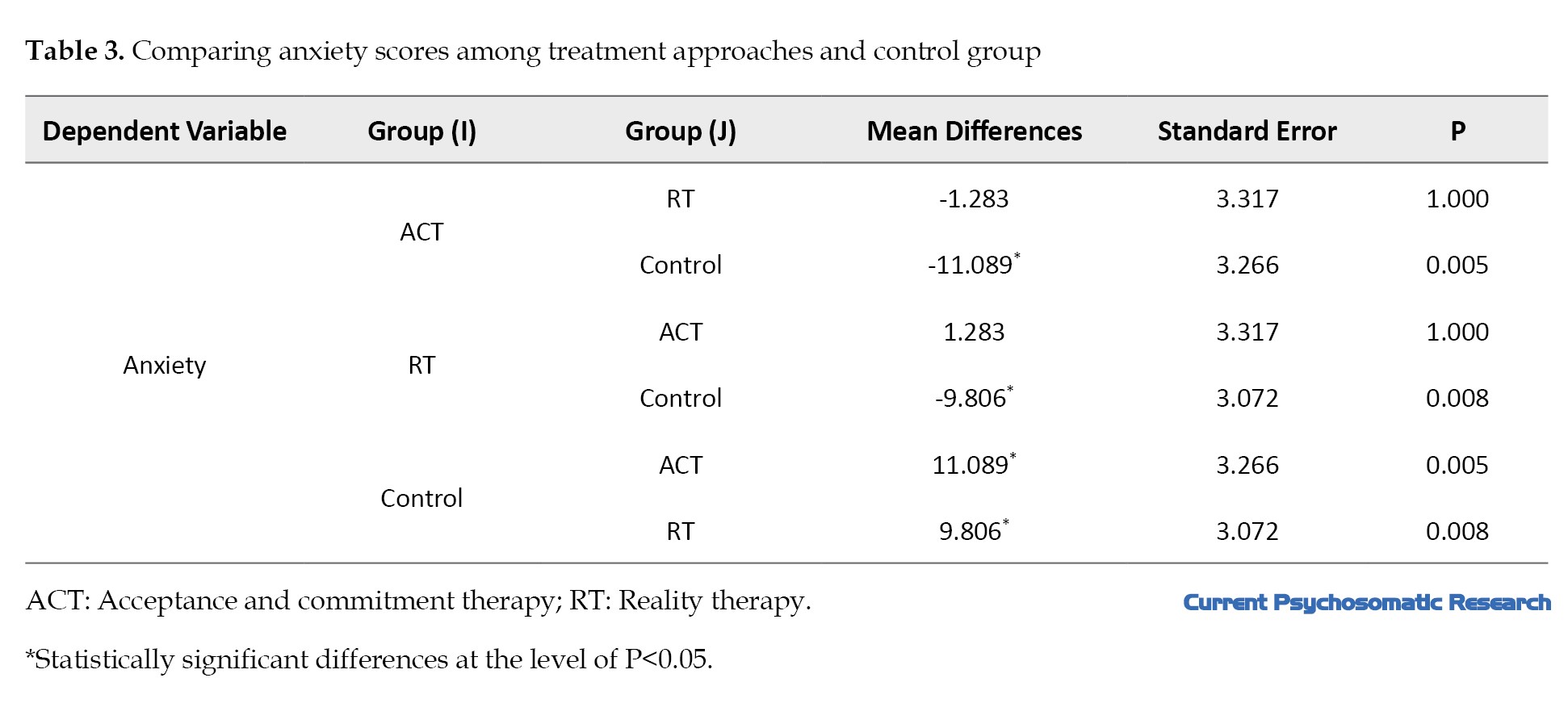

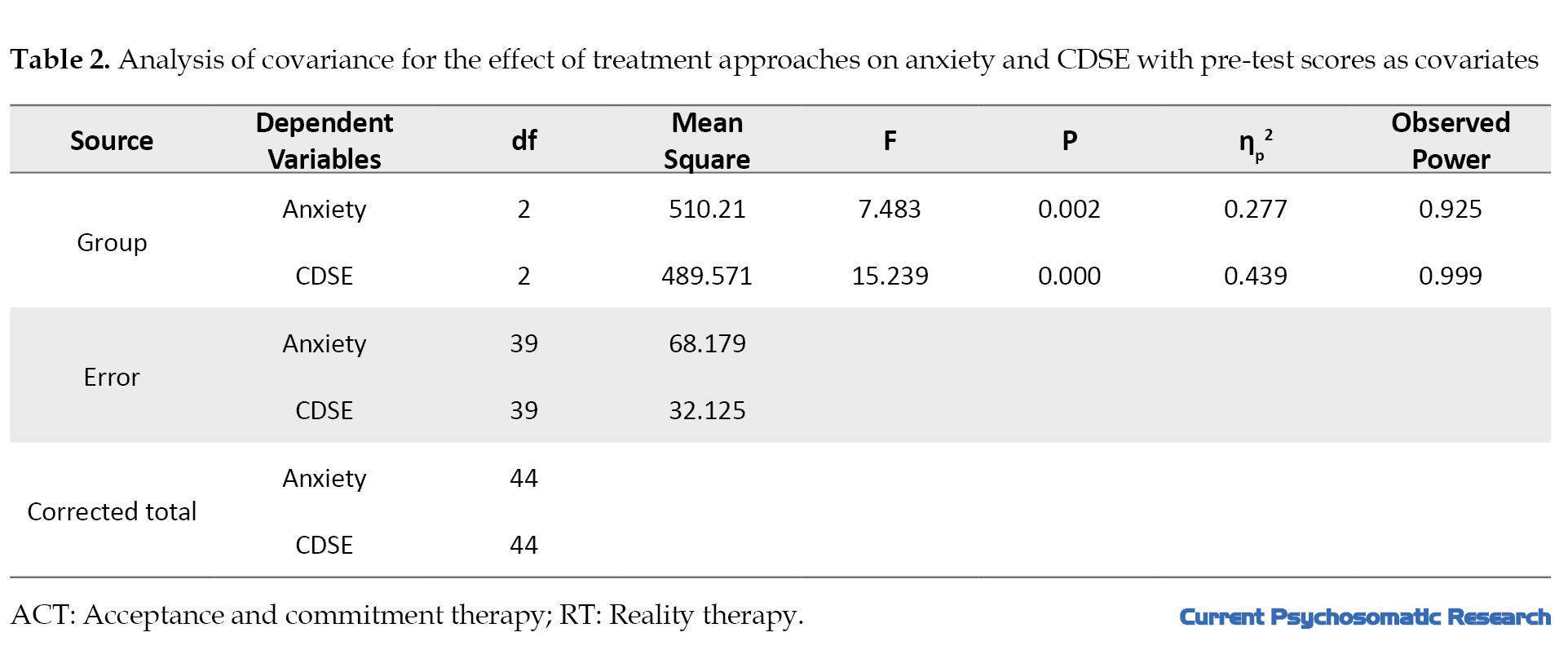

The mean anxiety scores in the control group were significantly higher than those in the ACT and RT groups, suggesting that both therapies could significantly reduce anxiety compared to the control group. Specifically, the mean difference in anxiety between the control and ACT groups was -11.089 (P=0.005), and the mean difference between the control and RT groups was -9.806 (P=0.008), both of which were significant. Additionally, there was a non-significant difference of 1.283 between the ACT and RT groups, indicating the similar effectiveness of the two treatment methods in reducing anxiety (Table 3).

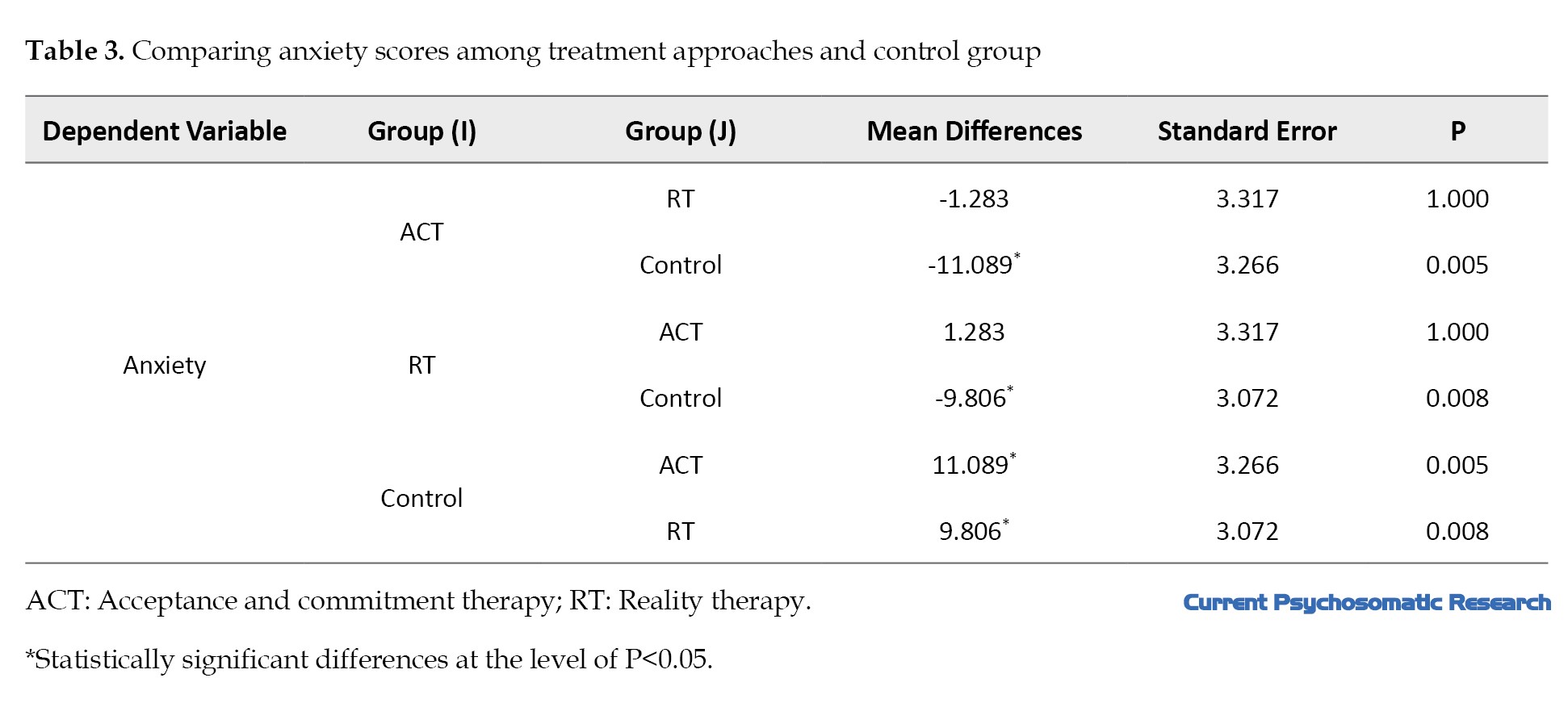

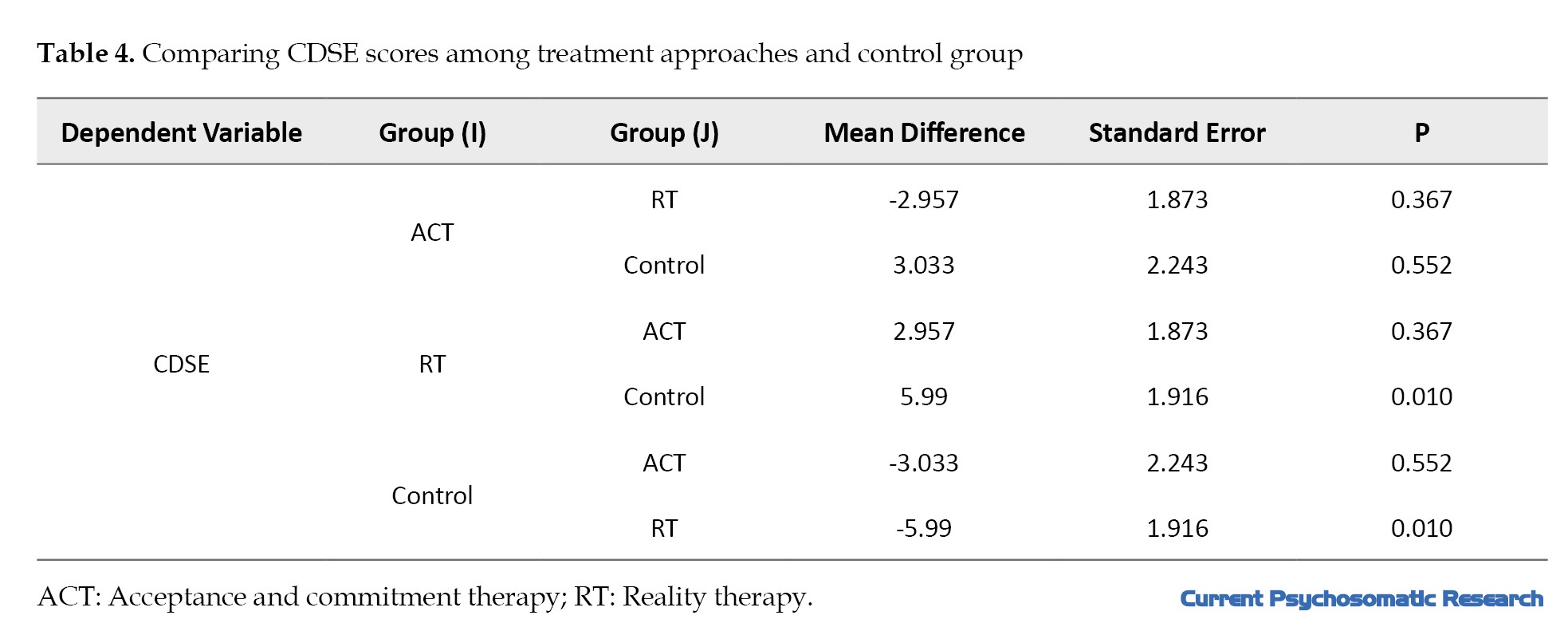

Only the RT group could significantly affect CDSE compared to the control group, with a mean difference of 5.990 (P=0.010; Table 4).

No significant differences were found between the ACT and RT groups (P=0.367) or between the ACT and control groups (P=0.552). Therefore, the RT group showed a significant improvement in CDSE compared to the control group, while the ACT group did not demonstrate significant effects on CDSE.

Clinical significance

In addition to statistical significance, clinical significance was assessed using the reliable change index (RCI) and minimal clinically important difference (MCID). The RCI was calculated for anxiety and CDSE to determine meaningful change at the individual level.

For anxiety, the RCI was set at 6 points based on previous studies. The results showed that 73.3% of participants in the ACT group and 53.5% in the RT group experienced a clinically significant anxiety reduction. In contrast, only 6.7% of participants in the control group achieved such a reduction.

For CDSE, the RCI threshold was 10 points. In the RT group, 64.2% of participants showed a clinically significant improvement, compared to 20% in the ACT group and 13/3% in the control group.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of ACT and RT in reducing anxiety and improving CDSE among adolescents. Both ACT and RT significantly reduced students’ anxiety (P<0.01). This suggests that the two therapies were similarly effective in alleviating anxiety, which is consistent with the key concerns highlighted in the introduction regarding adolescent mental health, particularly the role of anxiety in decision-making processes, as evidenced in studies by Chegini et al. [6] and Jalali Azar et al. [15]. Additionally, other studies, such as those by Farmani et al. [26], Etemadi et al. [27], have shown that RT significantly impacts anxiety, aligning with our findings. There was no notable difference in the effectiveness of the two therapies. However, Figueiredo et al. [28] reported a more pronounced effect of ACT on anxiety, suggesting that the underlying mechanisms of each therapy might uniquely influence different aspects of mental health.

The similar effect of ACT and RT on anxiety can be explained by the fact that both therapies share key principles related to mental health. As mentioned in the introduction, both therapies focus on psychological flexibility and the ability to manage uncontrollable aspects of life. Both approaches help individuals accept uncontrollable events and empower them to focus on what can be changed. In RT, for example, “plan A” and “plan B” are used to address unsolvable and solvable issues, respectively. Both therapies teach students that, despite challenges in their environment, family, academics, or social life, they have the power to make choices within their control. This shift in focus from what is uncontrollable to what is manageable helps facilitate change. Moreover, both therapies incorporate strategic, value-driven planning that enables students to tackle life challenges more effectively.

The results also indicated that only RT significantly improved CDSE. While the literature does not often compare the effects of ACT and RT on CDSE, Hashemi et al. found that RT positively impacted CDSE, which aligns with our findings [29]. This suggests that RT’s emphasis on responsibility and goal-setting plays a central role in improving self-efficacy in career decision-making, particularly in adolescents. RT may enhance CDSE by encouraging individuals to develop self-efficacy and self-esteem through practical, goal-oriented approaches. RT teaches individuals to create a framework for satisfying their basic needs, set goals based on that framework, and take actionable steps toward those goals using well-structured plans. Additionally, RT places a strong emphasis on communication skills, which may be especially beneficial for adolescents as they navigate relationships with parents and teachers.

This study faced limitations, including the inability to control for gender and age differences and its focus on a single city, Yazd. Additionally, a chemical attack on girls’ schools during the study forced researchers to conduct two sessions online, and follow-up studies could not be carried out. Future research should consider a national sample, include male students, and involve longer follow-up periods. Despite these limitations, the study suggests that both ACT and RT are effective in reducing anxiety, with RT being more effective in improving CDSE among adolescent girls.

Conclusion

Both ACT and RT effectively reduce anxiety in female adolescents, with RT also significantly enhancing CDSE. While both therapies promote psychological flexibility, RT’s focus on responsible decision-making and practical goal-setting makes it particularly useful for boosting CDSE. Clinically, these findings support the use of both ACT and RT in school-based mental health interventions, with RT being especially beneficial in career counseling and decision-making programs. Mental health professionals and educators can apply RT to help students develop decision-making confidence and self-efficacy, while ACT’s focus on acceptance and mindfulness can aid in anxiety management. Future research should explore the long-term effects of these therapies across diverse populations, including follow-up assessments, to further evaluate their sustained benefits.

thical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.YAZD.REC.1402.006). this study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (Code: 20241221064117N1). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, after explaining the study methods and objectives to them.

Funding

This study was derived from the master thesis of Najmeh Sedrpooshan, approved by the Department of Counselling, Faculty of Humanities, Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran.. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank and appreciate the cooperation of all participants in the present research.

The teenage period is a critical phase in life that shapes personality, career interests, and future job choices [1]. It involves cognitive, biological, social, and emotional changes, with effects that last throughout life [2]. One of the key concerns during adolescence is the transition to adulthood and the ability to make informed career decisions. Career readiness plays a crucial role in long-term professional success; however, many teenagers struggle with low self-efficacy in making career-related choices [3, 4]. Furthermore, adolescent mental health, particularly among female teenagers, is receiving increasing attention due to its impact on academic performance, social relationships, and overall well-being [2]. Various challenges during this period prevent individuals from reaching their full potential, making it crucial to identify these problems and address them early to ensure a healthier society [1]. Given the psychological challenges and external pressures affecting career decision-making during adolescence, enhancing career path decision-making self-efficacy (CDSE) becomes particularly important. As mentioned, these issues can hinder adolescents from realizing their full potential, making improvements in self-efficacy in this area crucial for both career success and mental well-being.

CDSE is one of the main challenges for teenagers, referring to their belief in their ability to handle tasks related to career decision-making [5]. External pressures often prevent individuals from making value-driven decisions [6]. Additionally, mental health factors, such as anxiety, significantly influence decision-making processes and career-related confidence. Psychological flexibility, the ability to cope with anxiety, fear of failure, and hopelessness, is essential for building self-efficacy [7]. Anxiety, a disabling state, affects various areas of life and is one of the most common mental disorders, characterized by emotional, behavioral, and physical symptoms [8, 9].

Several psychological interventions have been developed to address these issues; two well-known therapies for increasing CDSE and reducing anxiety are acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) [10] and reality therapy (RT) [11]. ACT focuses on psychological flexibility, teaching individuals that thoughts and feelings are temporary and do not define reality. By accepting pain and tension, people can make value-driven decisions despite discomfort [12]. ACT therapists aim to help clients become more aware of their thoughts and emotions and make choices based on their values [13]. ACT, which is part of the third wave of behavioral therapies, enhances psychological flexibility through mindful acceptance and value-based planning [14]. Research shows that ACT improves self-efficacy and reduces anxiety, depression, and stress [15].

RT, on the other hand, argues that human behavior is driven by internal needs rather than external conditions [16]. Through choice theory, RT helps individuals make responsible decisions and manage emotions, such as anxiety [17]. RT encourages people to take control of their behavior rather than trying to control others. Its main goal is to help individuals understand their needs and make effective choices [17]. RT emphasizes responsibility and planning as essential human needs, arguing that failure to address them leads to mental health issues, like depression and anxiety [18]. Additionally, RT improves self-efficacy and reduces anxiety [19].

Although both ACT and RT belong to the third wave of behavioral therapies and emphasize values and planning, ACT uses mindfulness techniques and highlights the futility of controlling thoughts and feelings [20], while RT focuses on responsible decision-making without this emphasis. Despite the growing body of literature on ACT and RT, a direct comparison of their effectiveness in addressing CDSE and anxiety among adolescents is lacking. This research gap underscores the need for comparative studies that can clarify their relative impact.

Based on the outlined background, this study aimed to fill this gap by comparing the effectiveness of ACT and RT in addressing CDSE and reducing anxiety among female high school students. Comparing these approaches could provide valuable insights into behavioral therapies.

Based on the outlined background, the objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of ACT and RT in addressing CDSE and reducing anxiety among female high school students. Given the significance of the teenage period in shaping personality, career choices, and mental health, this study aimed to evaluate how these two third-wave behavioral therapies, with their differing emphases on psychological flexibility and responsibility, impact teenagers’ abilities to make informed career decisions and manage anxiety. The findings may provide insights into the relative strengths of ACT and RT in enhancing CDSE and reducing anxiety in adolescents. Additionally, the findings may contribute to a deeper understanding of the strengths and limitations of each approach, guiding future interventions aimed at improving adolescent career readiness and mental well-being.

Materials and Methods

The study population consisted of all female high school students in Yazd who were studying in the 2022-2023 academic year. Using cluster sampling, Region 2 of Yazd was selected, and one school from this region was chosen as the sample. Based on Cohen’s (2013) guidelines [21], a sample size of 12 to 15 participants per group was considered. A total of 45 students were selected through convenience sampling and were then randomly divided into three groups: 15 in the ACT group, 14 in the RT group, and 15 in the control group. Ultimately, one participant from the RT group dropped out. In the next step, the participants responded to the Beck anxiety scale (1988) and CDSE scale by Betz and Taylor (1983) during two stages of the research: Pre-test and post-test [24]. Participants in the intervention group received ACT and RT training in a group format (as training and skill development) for two months, with one session each week, and each session lasting 90 minutes. However, no training was delivered to the control group. Inclusion criteria were being a student at a secondary school, being a girl, residing in Yazd City, having not experienced stressful events in the past six months, and not receiving psychological treatment simultaneously for anxiety disorder. The exclusion criteria were the occurrence of a significant stressful life event, the initiation of psychiatric medication use, and students being absent from the research process for two consecutive sessions or three irregular sessions.

Research tools

Anxiety inventory

This scale was developed by Beck (1988) and consists of 21 items scored using four options. The internal consistency coefficient (α) for this scale was 0.82, indicating good reliability [22]. The validity of the Persian version was tested using the test re-test method with a one-week interval (0.75), and its item correlation varied from 0.30 to 0.76 [23].

CDSE

This 2-item scale was developed by Betz et al. in 1983 [24]. It evaluates five capacities related to career choice based on Crites’s model (1961). For example, this scale includes items, such as 1) Proper self-evaluation, 2) Gathering career information, 3) Choosing a goal, 4) Planning for the future, and 5) Problem-solving. The scale is scored using a four-point scale, ranging from lack of self-confidence to complete self-confidence. Betz et al. (1996) calculated and confirmed its reliability using Cronbach’s α (0.97) [24]. In Iran, the reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s α (0.78) [25].

ACT protocol

This protocol was developed by Hayes in 2004 and consists of eight sessions. It combines four approaches: Awareness, acceptance, commitment, and behavior change. It aims to achieve psychological flexibility, allowing individuals to act based on perceived values despite experiencing negative feelings [10]. The first intervention group was designated as the ACT group.

The ACT sessions followed a structured approach. Participants began with a pre-test, evaluation, and diagnostic interview. The first session introduced ACT concepts and challenged control strategies, followed by training in creative hopelessness and exploring unresolved issues in the second session. The third session focused on fostering acceptance and mindfulness, while the fourth emphasized living and choosing based on values. The fifth and sixth sessions refined participants’ goals, values, and actions, addressing barriers and promoting commitment. The seventh session aimed to remove obstacles to committed actions and concluded with a post-test, and the final session included evaluations and therapy adjustments.

RT protocol

This protocol was developed by Wubbolding in 2017 and consists of “reality,” “responsibility,” and “right and wrong differentiation.” The RT school stated that individuals suffer from human, social, and global situations in addition to mental and physical diseases. Accordingly, the failure of individuals to achieve their basic needs causes their behaviors to deviate from defined norms. Since necessary needs are considered a part of individuals’ lives, RT does not address past problems. Furthermore, the principles of this therapy do not involve the difficulties related to unconscious issues. RT emphasizes problem-solving and focuses on the present situation of the individual. It offers better options for the future of individuals through training. In RT, individuals are guided to understand what they want and how they can behave to achieve their goals effectively [11]. RT training was delivered to the second intervention group based on the Glasser model. The RT sessions began with a briefing to outline regulations, build group communication, administer a pre-test, and share the training plan. The first session introduced group members, objectives, and the history of choice theory. The second session focused on human behavior and the five basic needs, while the third covered internal/external control, as well as the ten principles of choice theory. The fourth session introduced the concepts of the real and ideal worlds, behavior components, and the behavior machine. The fifth session focused on building realistic goals, while the sixth session addressed planning to achieve them. The seventh session covered practical steps using ability cards, and the eighth session emphasized responsibility and concluded with a summary.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the distribution of the dependent variables, and Levene’s test was applied to evaluate the equality of error variance across groups. Additionally, the M-Box test was used to examine the homogeneity of variance-covariance. To analyse the overall effect of the independent variable (treatment method) on the dependent variables, multivariate analyses using criteria, such as Pillai’s trace, Wilks’ lambda, Hotelling’s trace, and Roy’s largest root, were utilized. Furthermore, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to compare the post-test scores between the groups while controlling for pre-test scores. Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to determine pairwise differences. SPSS software, version 23, was used to analyze data at a significance level of P<0.05.

Results

The sample consisted of 44 unmarried female high school students from Yazd City. The mean age of the participants was 16.2±0.87 years, ranging from 15 to 17 years. A one-way ANOVA was used to examine the effect of age across the three groups, and the results indicated that age had no significant impact on the study outcomes.

As shown in Table 1, anxiety scores decreased significantly in both the ACT and RT groups, whereas the control group showed no meaningful change.

Regarding CDSE, the RT group demonstrated the highest improvement, while the ACT and control groups showed smaller increases.

To statistically analyze these changes, a repeated measures ANOVA was conducted and the results indicated a significant interaction effect between time (pre-test vs. post-test) and group for both anxiety (F=15.872, P<0.001, η²=0.388) and CDSE (F=12.461, P<0.001, η²=0.351). Bonferroni post-hoc tests confirmed that the ACT and RT groups experienced significant improvements compared to the control group (P<0.01 for all comparisons).

To consider the pre-requisite conditions for parametric analysis, we used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess the normal distribution of dependent variables. The results showed that the anxiety variable did not significantly deviate from normality (P=0.0625), indicating that the normality assumption was not violated. However, for CDSE, the normality assumption was violated (P=0.0165), suggesting that the distribution of CDSE scores significantly deviated from normal. Therefore, parametric analyses could not be conducted for CDSE without further adjustments.

To assess the equality of error variance of the dependent variable across groups, we used the Levene test. The significance levels for both anxiety (P=0.105) and CDSE (P=0.557) were greater than 0.05. Therefore, the assumption of equal error variance was not rejected for either variable, indicating that the groups did not significantly differ in terms of variability.

We used the M-Box test to assess the homogeneity of variances and covariances. The treatment approach had a significant effect on the dependent variables, as indicated by all four multivariate criteria. Pillai’s trace (F=7.291, P=0.000), Wilks’ lambda (F=8.402, P=0.000), Hotelling’s trace (F=9.507, P=0.000), and Roy’s largest root (F=18.998, P=0.000) all yielded significant results with high observed power (ranging from 0.994 to 1). These findings suggest that the combination of the independent variable (treatment approach) significantly impacts the dependent variables, supporting the efficacy of the intervention.

The treatment approaches had a significant effect on both anxiety and CDSE. Specifically, the F-values for anxiety (F=7.483, P=0.002) and CDSE (F=15.239, P=0.000) suggest a significant treatment effect. Additionally, the partial eta squared values of 0.277 for anxiety and 0.439 for CDSE indicated that 27% and 44% of the variance in these variables, respectively, was explained by the type of therapy or treatment approach. The observed power values of 0.925 for anxiety and 0.999 for CDSE indicated a strong statistical power for detecting the effects of the treatments. In the next step, Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to compare the treatment groups (Table 2).

The mean anxiety scores in the control group were significantly higher than those in the ACT and RT groups, suggesting that both therapies could significantly reduce anxiety compared to the control group. Specifically, the mean difference in anxiety between the control and ACT groups was -11.089 (P=0.005), and the mean difference between the control and RT groups was -9.806 (P=0.008), both of which were significant. Additionally, there was a non-significant difference of 1.283 between the ACT and RT groups, indicating the similar effectiveness of the two treatment methods in reducing anxiety (Table 3).

Only the RT group could significantly affect CDSE compared to the control group, with a mean difference of 5.990 (P=0.010; Table 4).

No significant differences were found between the ACT and RT groups (P=0.367) or between the ACT and control groups (P=0.552). Therefore, the RT group showed a significant improvement in CDSE compared to the control group, while the ACT group did not demonstrate significant effects on CDSE.

Clinical significance

In addition to statistical significance, clinical significance was assessed using the reliable change index (RCI) and minimal clinically important difference (MCID). The RCI was calculated for anxiety and CDSE to determine meaningful change at the individual level.

For anxiety, the RCI was set at 6 points based on previous studies. The results showed that 73.3% of participants in the ACT group and 53.5% in the RT group experienced a clinically significant anxiety reduction. In contrast, only 6.7% of participants in the control group achieved such a reduction.

For CDSE, the RCI threshold was 10 points. In the RT group, 64.2% of participants showed a clinically significant improvement, compared to 20% in the ACT group and 13/3% in the control group.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of ACT and RT in reducing anxiety and improving CDSE among adolescents. Both ACT and RT significantly reduced students’ anxiety (P<0.01). This suggests that the two therapies were similarly effective in alleviating anxiety, which is consistent with the key concerns highlighted in the introduction regarding adolescent mental health, particularly the role of anxiety in decision-making processes, as evidenced in studies by Chegini et al. [6] and Jalali Azar et al. [15]. Additionally, other studies, such as those by Farmani et al. [26], Etemadi et al. [27], have shown that RT significantly impacts anxiety, aligning with our findings. There was no notable difference in the effectiveness of the two therapies. However, Figueiredo et al. [28] reported a more pronounced effect of ACT on anxiety, suggesting that the underlying mechanisms of each therapy might uniquely influence different aspects of mental health.

The similar effect of ACT and RT on anxiety can be explained by the fact that both therapies share key principles related to mental health. As mentioned in the introduction, both therapies focus on psychological flexibility and the ability to manage uncontrollable aspects of life. Both approaches help individuals accept uncontrollable events and empower them to focus on what can be changed. In RT, for example, “plan A” and “plan B” are used to address unsolvable and solvable issues, respectively. Both therapies teach students that, despite challenges in their environment, family, academics, or social life, they have the power to make choices within their control. This shift in focus from what is uncontrollable to what is manageable helps facilitate change. Moreover, both therapies incorporate strategic, value-driven planning that enables students to tackle life challenges more effectively.

The results also indicated that only RT significantly improved CDSE. While the literature does not often compare the effects of ACT and RT on CDSE, Hashemi et al. found that RT positively impacted CDSE, which aligns with our findings [29]. This suggests that RT’s emphasis on responsibility and goal-setting plays a central role in improving self-efficacy in career decision-making, particularly in adolescents. RT may enhance CDSE by encouraging individuals to develop self-efficacy and self-esteem through practical, goal-oriented approaches. RT teaches individuals to create a framework for satisfying their basic needs, set goals based on that framework, and take actionable steps toward those goals using well-structured plans. Additionally, RT places a strong emphasis on communication skills, which may be especially beneficial for adolescents as they navigate relationships with parents and teachers.

This study faced limitations, including the inability to control for gender and age differences and its focus on a single city, Yazd. Additionally, a chemical attack on girls’ schools during the study forced researchers to conduct two sessions online, and follow-up studies could not be carried out. Future research should consider a national sample, include male students, and involve longer follow-up periods. Despite these limitations, the study suggests that both ACT and RT are effective in reducing anxiety, with RT being more effective in improving CDSE among adolescent girls.

Conclusion

Both ACT and RT effectively reduce anxiety in female adolescents, with RT also significantly enhancing CDSE. While both therapies promote psychological flexibility, RT’s focus on responsible decision-making and practical goal-setting makes it particularly useful for boosting CDSE. Clinically, these findings support the use of both ACT and RT in school-based mental health interventions, with RT being especially beneficial in career counseling and decision-making programs. Mental health professionals and educators can apply RT to help students develop decision-making confidence and self-efficacy, while ACT’s focus on acceptance and mindfulness can aid in anxiety management. Future research should explore the long-term effects of these therapies across diverse populations, including follow-up assessments, to further evaluate their sustained benefits.

thical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.YAZD.REC.1402.006). this study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (Code: 20241221064117N1). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, after explaining the study methods and objectives to them.

Funding

This study was derived from the master thesis of Najmeh Sedrpooshan, approved by the Department of Counselling, Faculty of Humanities, Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran.. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank and appreciate the cooperation of all participants in the present research.

References

- Khalaf AM, Alubied AA, Khalaf AM, Rifaey AA, Alubied A, Rifaey A. The impact of social media on the mental health of adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e42990. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.42990]

- Delforooz S, Ebrahimi M I, Mirhashemi M, Ghodsi P. [Develop a Model of adolescent psychological well-being based on basic needs, parent-child relationship and responsibility mediated by self-efficacy (Persian)]. Pajouhan Sci J. 2022; 20(1):7-15.[DOI:10.61186/psj.20.1.7]

- Yazdi-Ravandi S, Matinnia N, Haddadi A, Tayebi M, Mamani M, Ghaleiha A. Assessing depression, anxiety, perceived stress, and job burnout in hospital medical staff during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Hamedan, Iran. 2019. Curr Psychiatry Res Rev. 2024; 20(3):228-42. [DOI:10.2174/0126660822262216231120062102]

- Wang PY, Lin PH, Lin CY, Yang SY, Chen KL. Does interpersonal interaction really improve emotion, sleep quality, and self-efficacy among junior college students? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4542. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17124542] [PMID]

- Agoes Salim RM, Istiasih MR, Rumalutur NA, Biondi Situmorang DD. The role of career decision self-efficacy as a mediator of peer support on students’ career adaptability. Heliyon. 2023; 9(4):e14911. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14911] [PMID]

- Chegini L, Ebrahimi MI, Sahebi A. [The effect of choice theory training to parents on the aggression of their children in elementary school (Persian)]. J Child Ment Heal. 2019; 6(1):70-82. [DOI:10.29252/jcmh.6.1.7]

- Afshari E, Ebrahimi MI, Haddadi A. The Effect of Acceptance and Commitment Group Therapy on Emotional Divorce and Self-efficacy of Working Couples. J Community Health Res. 2022; 11(4):327-36. [DOI:10.18502/jchr.v11i4.11734]

- Leichsenring F, Heim N, Steinert C. A review of anxiety disorders. JAMA. 2023; 329(15):1315-6. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2023.2428] [PMID]

- Haddadi A, Matinnia N, Yazdi-Ravandi S. The relationship between corona disease anxiety and sleep disturbances and suicidal ideation in medical staff: The mediating role of resiliency and cognitive flexibility: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2024; 7(8):e2282. [DOI:10.1002/hsr2.2282] [PMID]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Bunting K, Twohig M, Wilson KG. What is acceptance and commitment therapy? In: Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, editors. A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy. Boston: Springer; 2004. [DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-23369-7_1]

- Wubbolding R. Counselling with reality therapy. London: Routledge; 2017. [Link]

- Sevier-Guy LJ, Ferreira N, Somerville C, Gillanders D. Psychological flexibility and fear of recurrence in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021; 30(6):e13483. [DOI:10.1111/ecc.13483] [PMID]

- Ravanbakhsh L, Ebrahimi MI, Haddadi A, Yazdi-Ravandi S. Effects of the acceptance and commitment therapy on resiliency, self-compassion, and corona disease anxiety on medical staff involved in covid-19 pandemic. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2023; 17(4):e136845. [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs-136845]

- El Rafihi-Ferreira R, Morin CM, Toscanini AC, Lotufo Neto F, Brasil IS, Gallinaro JG, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy-based behavioral intervention for insomnia: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021; 43(5):504-9. [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0947] [PMID]

- Jalali Azar R, Ebrahimi MI, Haddadi A, Yazdi-Ravandi S. The impact of acceptance and commitment therapy on college students’ suicidal ideations, a tendency to self-harm, and existential anxiety. Curr Psychol. 2023; 43:15649–58.[DOI:10.1007/s12144-023-05501-4]

- Yadolahi Saber F, Ebrahimi ME, Zamani N, Sahebi A. The effect of choice theory training on responsibility and hopefulness of female students Islamic Azad University Hamedan. Soc Cogn. 2019; 8(1):165-74. [DOI:10.30473/sc.2019.32877.2019]

- Robey PA, Wubbolding RE, Malters M. A comparison of choice theory and reality therapy to adlerian individual psychology. J Individ Psychol. 2017; 73(4):283-94. [DOI:10.1353/jip.2017.0024]

- Glasser W. Choice Theory: A new psychology of personal freedom. New York: HarperPerennial; 1999. [Link]

- Hadian S, Havasi Soomar N, Taghvaei H, Ebrahimi MI, Ranjbaripour T, Soomar NH. Comparing the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy and reality therapy on the responsibility and self-efficacy of divorced women. Adv Cogn Sci. 2023; 25(3):47-63. [DOI:10.30514/icss.25.3.47]

- Haddadi A, Yazdi-Ravandi S, Moradi A, Hajaghaie E. Comparison of the Resilience of the Medical Staff During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Response to The Effects of Yalom Group Psychotherapy and Acceptance and Commitment Group Therapy. J Res Health. 2023; 13 (3):227-36.[DOI:10.32598/JRH.13.3.1751.1]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge ; 2013. [DOI:10.4324/9780203771587]

- Beck AT, Steer RA.. Relationship between the Beck anxiety inventory and the Hamilton anxiety rating scale with anxious outpatients. J Anxiety Dis. 5:213–23. [DOI: 10.1016/0887-6185(91)90002-B]

- Rafee M, Seify A. An Investigation into the Reliability and Validity of Beck Anxiety Inventory among the University Students. Thoughts Behav Clin Psychol. 2013; 8(27):37-46. [Link]

- Betz NE, Klein KL, Taylor KM. Evaluation of a Short Form of the Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale. J Career Assess. 1996; 4(1):47-57. [DOI:10.1177/106907279600400103]

- Farhang R, Zamani Ahari U, Ghasemi S, Kamran A. The relationship between learning styles and career decision-making self-efficacy among medicine and dentistry students of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences. Educ Res Int. 2020; 2020(1):6662634. [Link]

- Farmani F, Taghavi H, Fatemi A, Safavi S. The efficacy of group reality therapy on reducing stress, anxiety and depression in patients with Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Int J Appl Behav Sci. 2015; 2(4):33-8. [DOI:10.22037/ijabs.v2i4.11421]

- Etemadi A, Nasirnejhad F, Smkhani Akbarinejhad H. Effectiveness of group reality therapy on the anxiety of women. J Psychol Stud. 2014; 10(2):73-88. [DOI:10.22051/psy.2014.1773]

- Figueiredo DV, Salvador MDC, Rijo D, Vagos P. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a transdiagnostic approach to adolescents with different anxiety disorders: Study protocol. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024 Nov 14. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-024-02608-2] [PMID]

- Hashemi N, Rahimi Pordanjani T, Barabadi HA. The effectiveness of group reality therapy based on Glaser’s choice theory on career self-efficacy. Ind Organ Psychol Stud. 2019; 5(2):103-120. [Link]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2024/12/17 | Accepted: 2024/04/1 | Published: 2024/04/1

Received: 2024/12/17 | Accepted: 2024/04/1 | Published: 2024/04/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |