Fri, Jan 30, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 1, Issue 3 (Spring 2023)

CPR 2023, 1(3): 346-359 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghanbari Jolfaei A, Zahedi Y, Pazouki A, Nooraeen S, Pir Hayati M. Relationship Between Coping Strategies and Outcome of Bariatric Surgery in Patients With Morbid Obesity. CPR 2023; 1 (3) :346-359

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-63-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-63-en.html

Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1751 kb]

(509 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1535 Views)

Full-Text: (575 Views)

Introduction

Obesity is a chronic condition characterized by an increase in body fat. The body fat content can be measured by the body mass index (BMI) which is defined as the ratio of body weight (in kilograms) to body height (in meters squared). In clinical definition, a BMI of 25–29 kg/m2 indicates overweight and a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 is considered obesity. Obesity is a serious public health problem worldwide [1]. Excessive amount of body fat is usually caused by an imbalance between consuming calories and the energy intake [2]. Sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy diet are other factors that can lead to obesity. The global obesity prevalence has led to an alarming increase in mortality rate and associated complications. Obesity has also significant economic and psychological consequences. Evidence suggests an association between obesity and eating disorders (especially binge eating disorder), substance use disorders, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder [2-4].

Morbid obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) has become a major health problem in many countries [1]. This disorder is often resistant to dietary regimen or medications. It also has a low response to psychotherapy or other conventional interventions [3], but it has responded well to bariatric surgery [5]. This treatment method has a favorable short-term and long-term effect in controlling weight and obesity complications [6]. Studies have shown that bariatric surgery can reduce and maintain weight and improve other health conditions [7, 8, 9]. Although bariatric surgery is an effective treatment for obesity, it was shown that the psychological factors can affect its outcome [10]. There is a need to obtain information about the psychological predictors of obesity after surgery [11, 12]. Stress is one of the effective psychological factors, because stressful conditions can lead to dietary problems, lack of exercise, and difficulty regulating emotions, each of which is involved in the development and persistence of obesity [13].

In addition, Stress can alter eating patterns [14-16]. In stressful situations, people use different thoughts and behaviors called “coping strategies”. These strategies are divided into two main categories, problem-focused and emotion-focused. In problem-focused strategies, the individual uses active methods and directly takes action to solve the cause of the problem. In emotion-focused strategies, a person regulates his/her feelings and emotional responses to tolerate stress. Studies have also shown that successful weight maintenance is associated with better coping strategies and better ability to manage life stressors. Eating in response to negative emotions and stress are the factors that can increase the risk of weight regain after bariatric surgery [17]. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the relationship between coping strategies and the outcome of bariatric surgery. The results can help develop psychological interventions before and after bariatric surgery.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This prospective/observational study was conducted on 85 patients with morbid obesity who were candidates for bariatric surgery in two general hospitals (Hazrat-e Rasoul Akram and Milad) in Tehran, Iran, who were selected by a convenience sampling method. They had 18-66 years of age, referred to obesity clinics to receive bariatric surgery (gastric bypass or mini-gastric bypass). First, medical history was recorded and the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 was used to ensure that patients had no endocrine or psychiatric disorders. Those with metabolic or hormonal disorders, major psychiatric disorders, and eating disorders were excluded from study. All participants received surgery by one surgery team and in one place and center. Their lifestyle, daily exercises, and family support were not evaluated. Their BMI was measured and coping strategies were evaluated. After two years, the outcome of the surgery was assessed by the Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS). In addition, their BMI was recorded again. After two years, 76 (90%) patients agreed to continue the study and 9 (10%) left the study.

Instruments

A demographic checklist was used to survey the demographic characteristics including age, gender, marital status, and cigarette smoking. Coping strategies were evaluated using the 66-item ways of coping questionnaire developed by Folkman & Lazarus in 1988. This questionnaire measures two strategies of problem-focused and emotion-focused. The problem-focused dimension measures four characteristics include seeking social support, accepting responsibility, planful problem-solving, and positive reappraisal. The emotion-focused dimension measures four characteristics of confrontive coping, distancing, self-controlling, and escape-avoidance. Folkman & Lazarus reported the reliability of its subscales from 0.61 for coping to 0.79 for positive reappraisal. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this tool have been confirmed in Iran [18]. The BAROS was used to evaluate the success of bariatric surgery. This questionnaire has 6 questions measuring weight loss and medical conditions. The total score is 9; a score of 1 or less indicates failure, a score >1-3 shows a fair outcome, a score > 3-5 indicates a good outcome, a score >5-7 shows a very good outcome, and a score >7-9 shows an excellent outcome. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this tool have been confirmed in Iran [19].

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS software, version 23 for data analysis. Correlation test and regression analysis were used to analyze the data. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

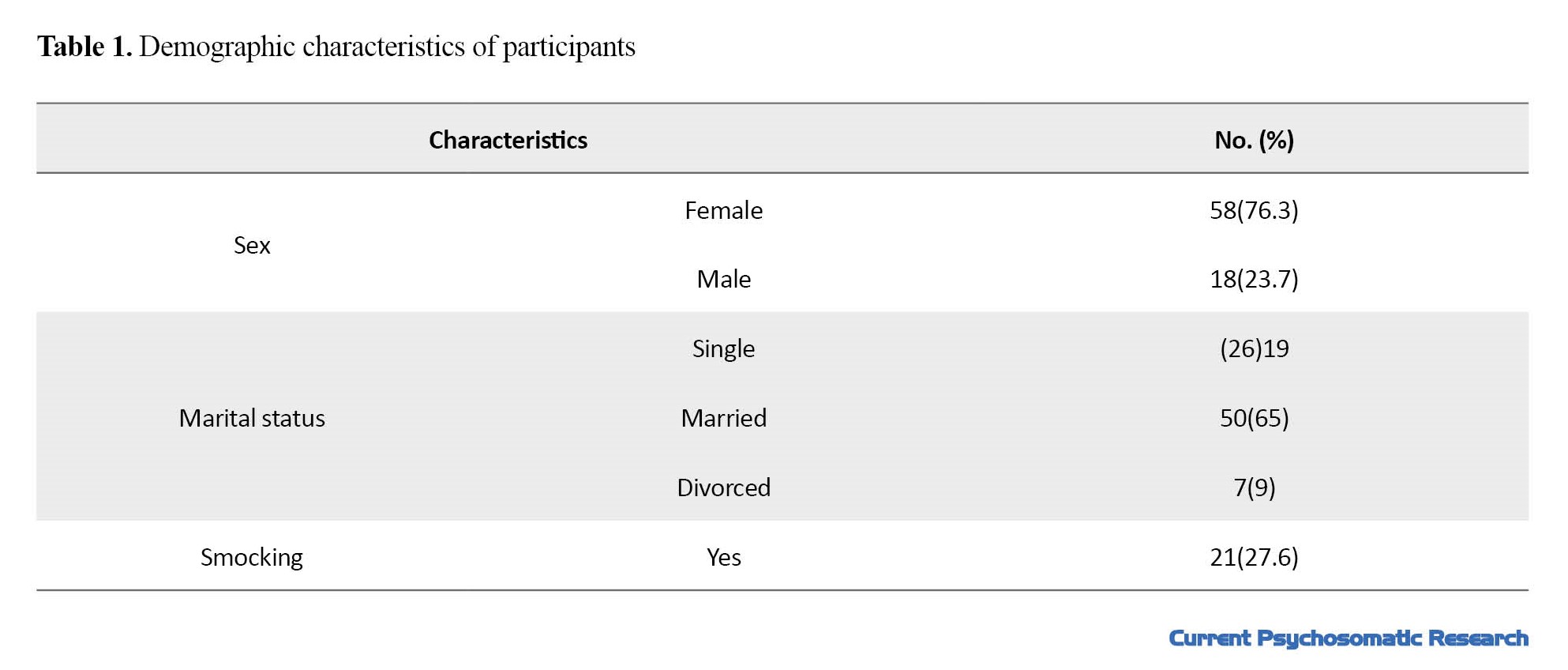

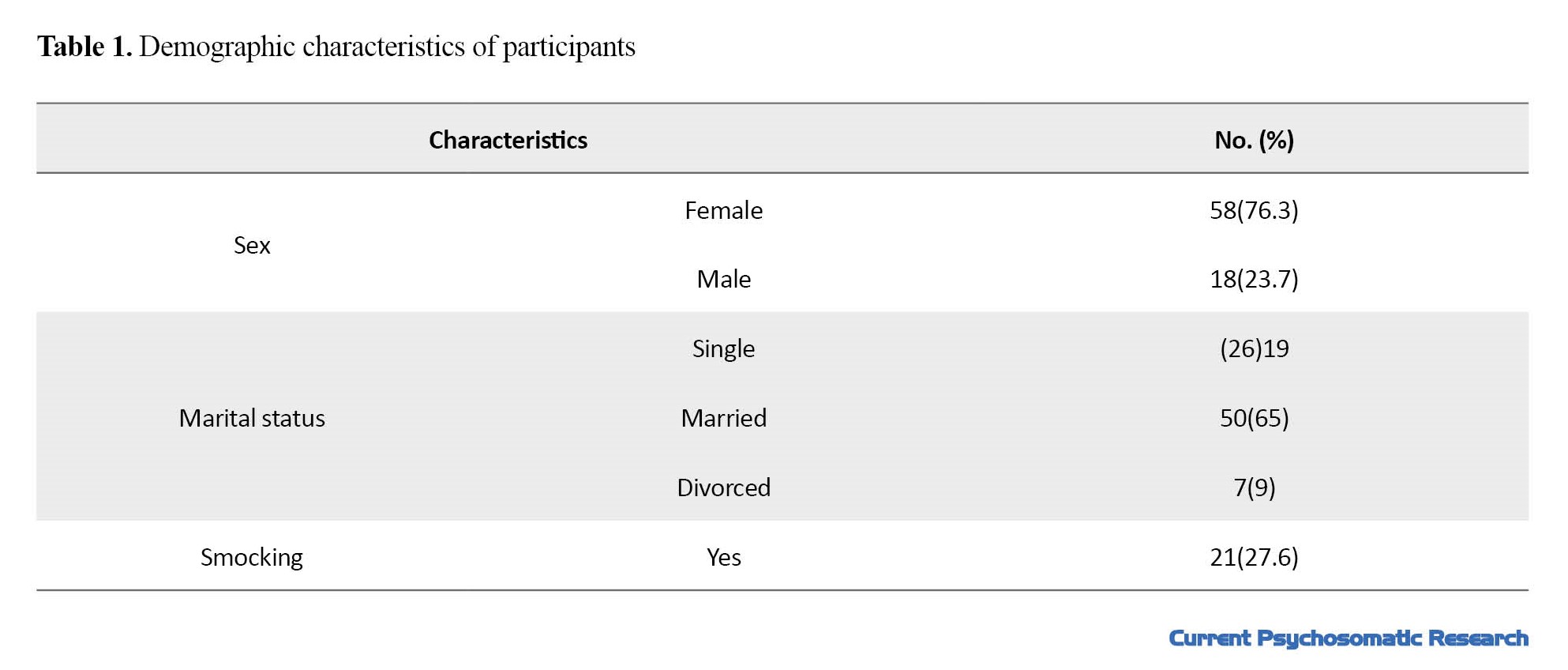

The mean age of participants was 38.11±11.5 years. There were 18 males (23.7%) and 58 females (76.3%); 25% (n=19) were single and 75% (n=57) were married. In terms of cigarette smoking, 27.6% (n=21) had a positive history (Table 1).

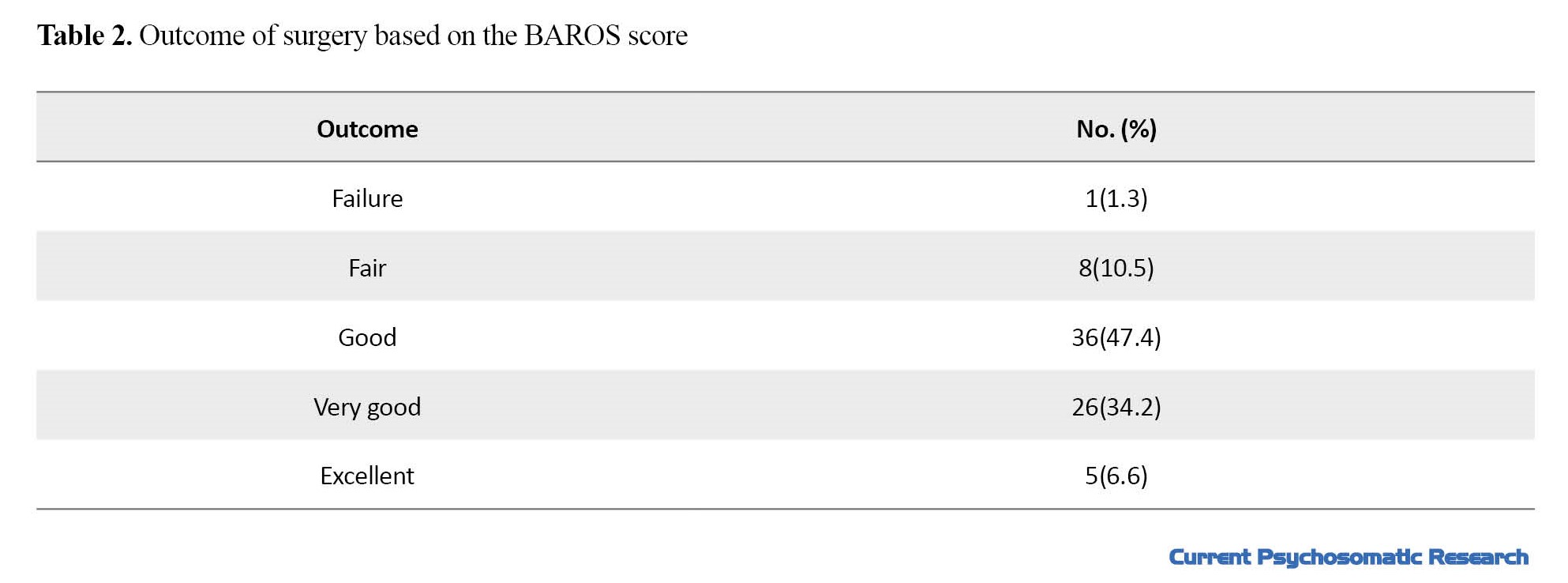

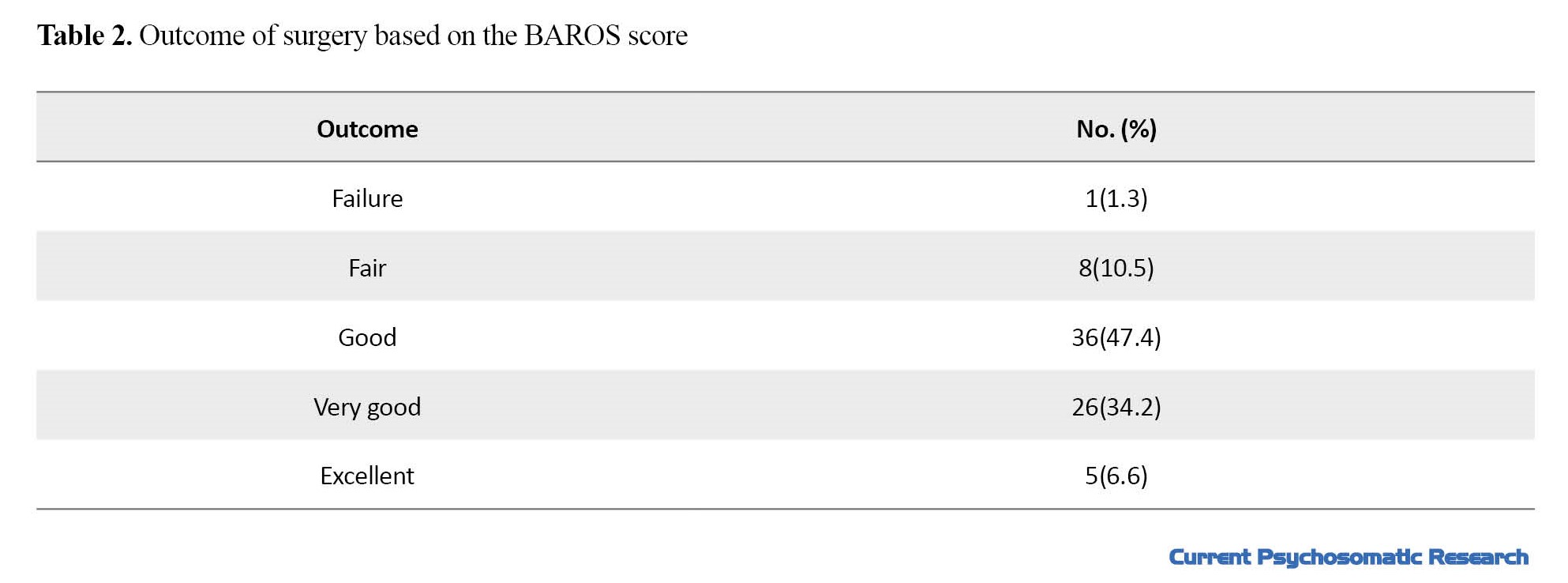

The mean score of BAROS was 4.6±1.4. The frequency of outcomes were as follows: 1 (1.3%) failure, 8 (10.5%) acceptable, 36 (47.4%) good, 26 (34.2%) very good, and 5 (6.6%) excellent (Table 2).

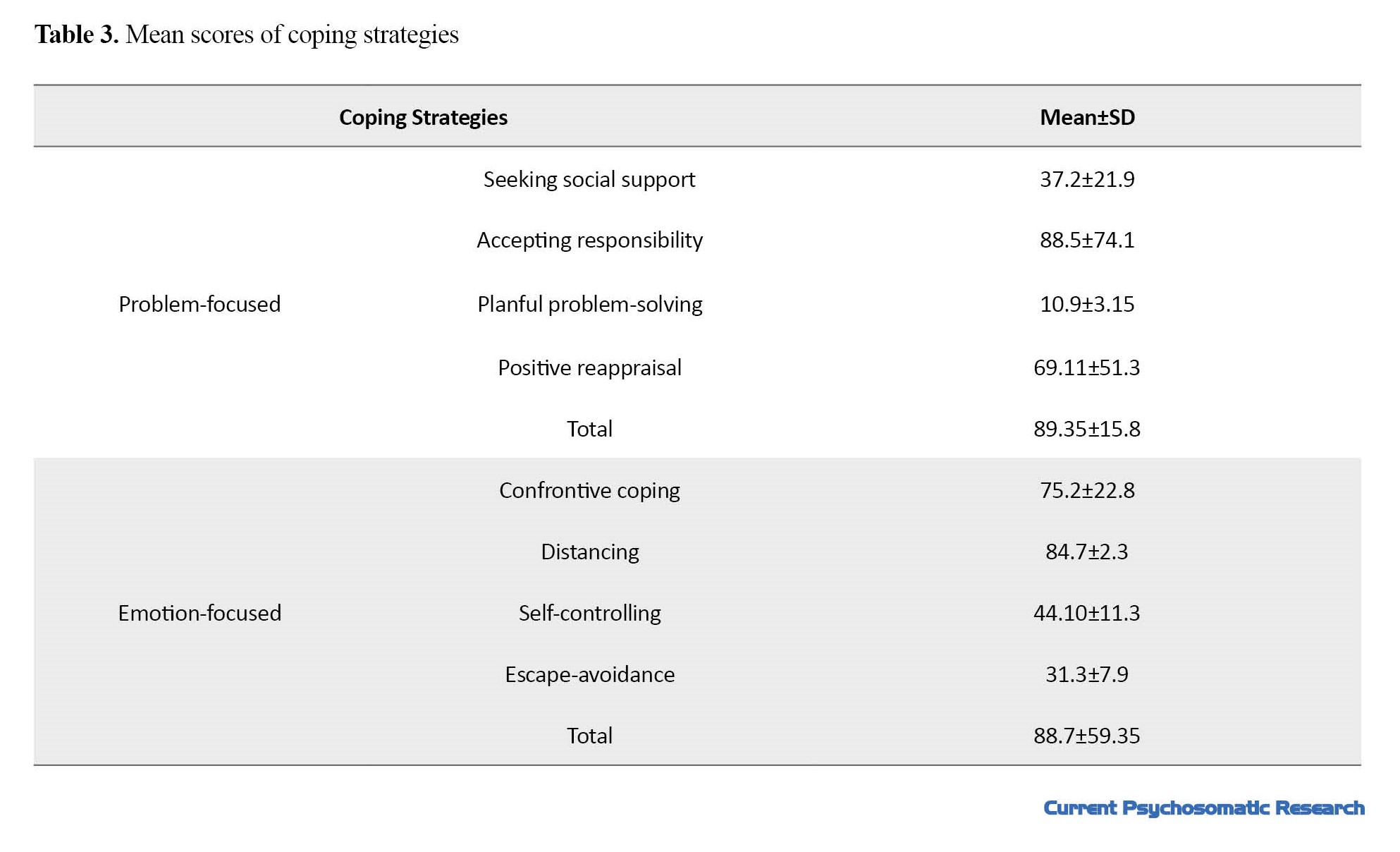

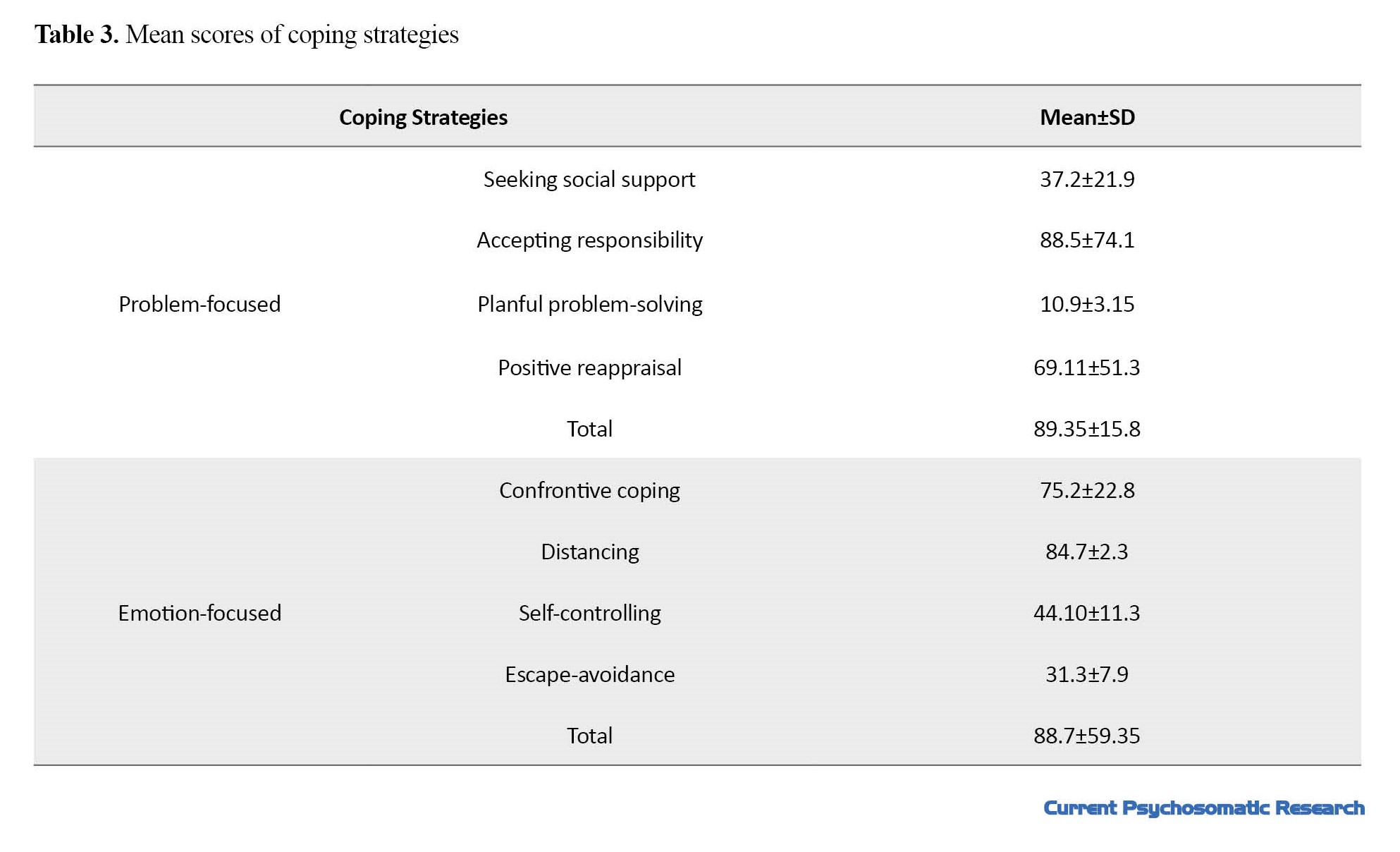

Table 3 shows the scores of copying strategies.

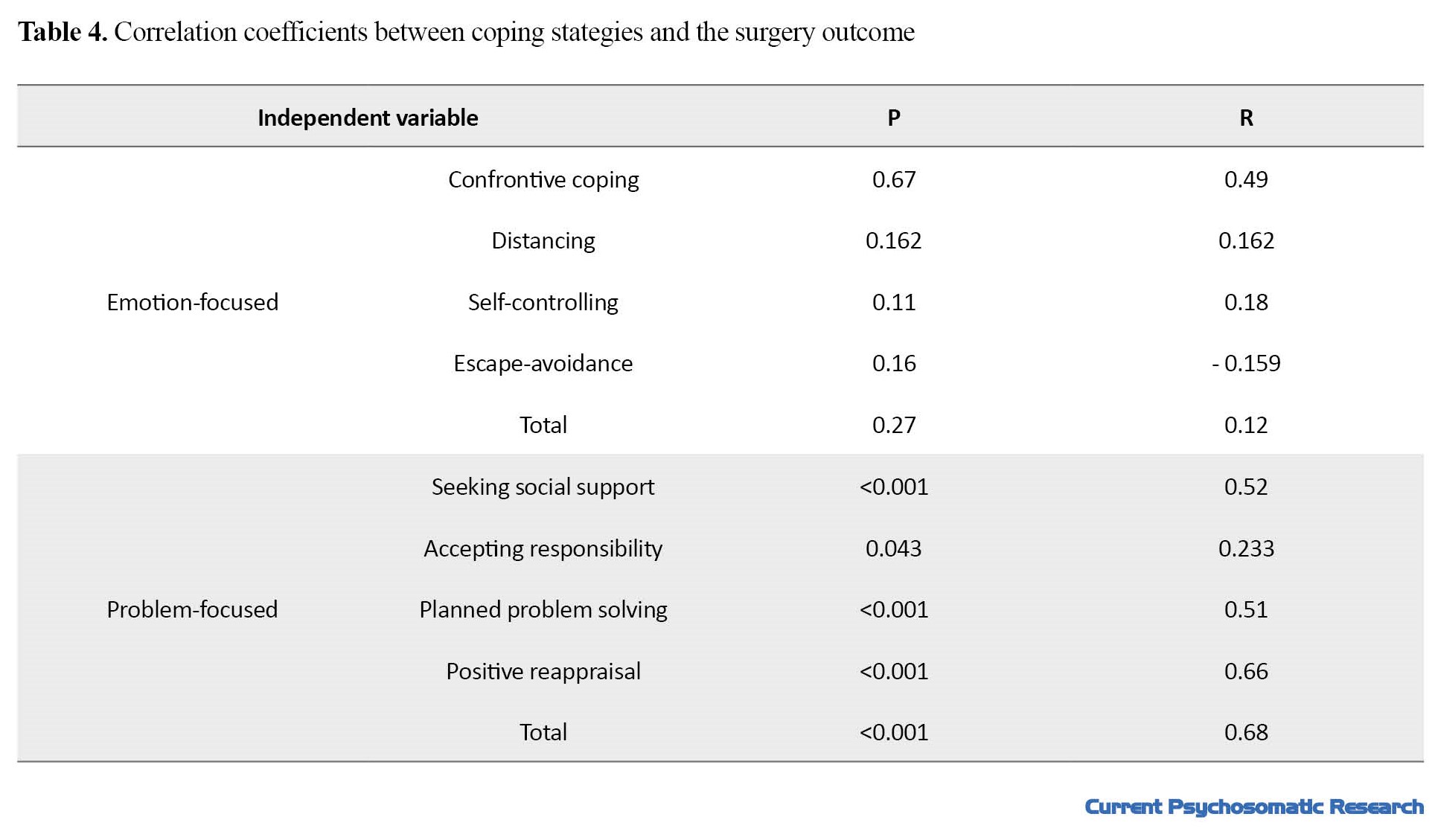

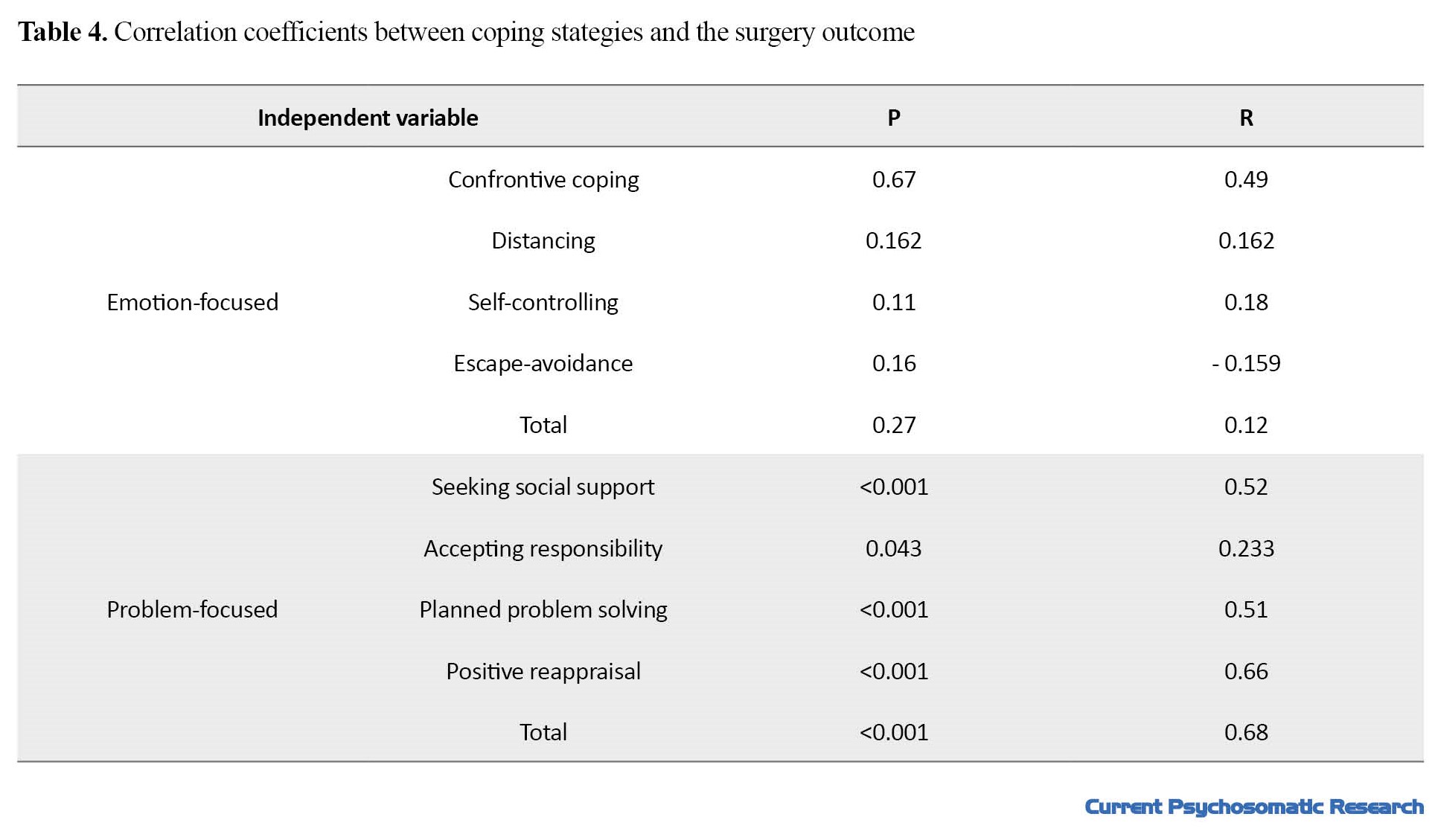

The mean total score of problem-focused coping strategies was 89.35 and the mean total score of emotion-focused coping strategies was 59.35. Table 4 shows the correlation coefficients between the domains of coping strategies and the outcome of surgery.

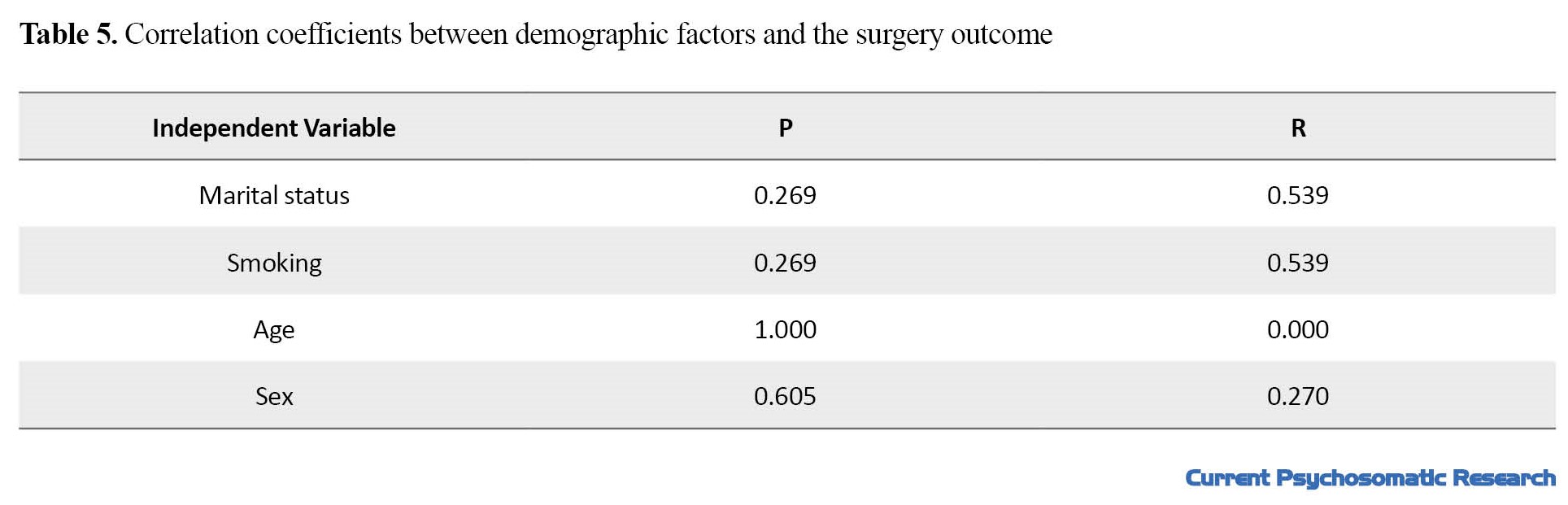

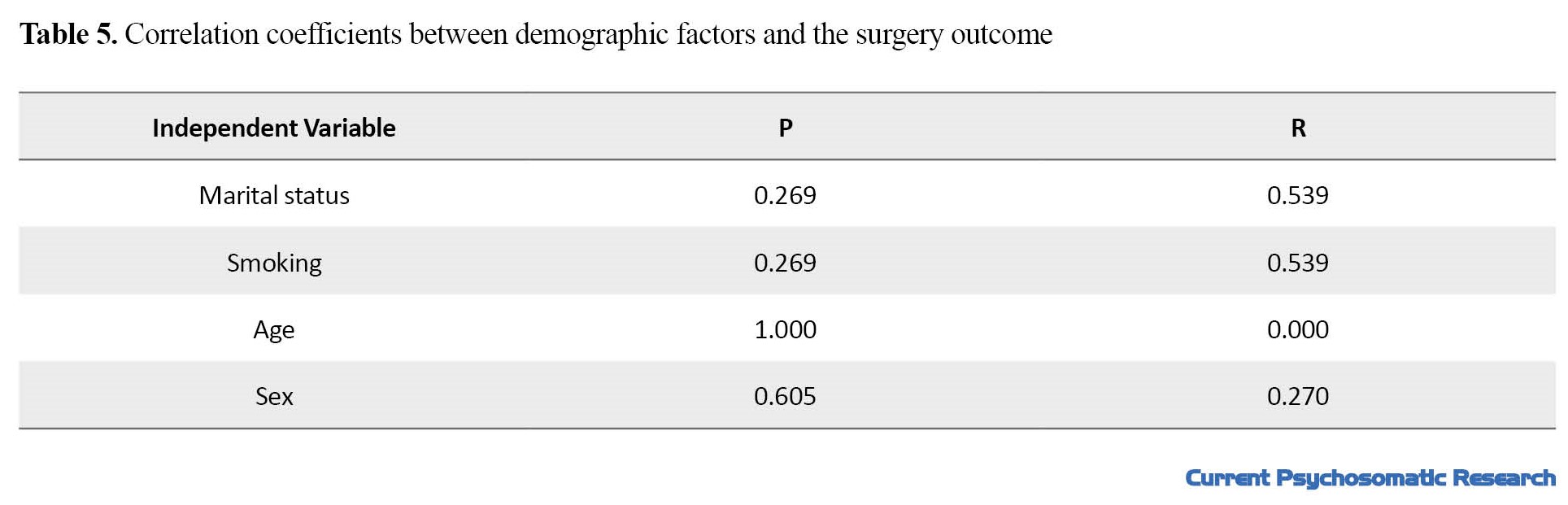

Table 5 presents the correlation coefficients between demographic factors and the surgery outcome.

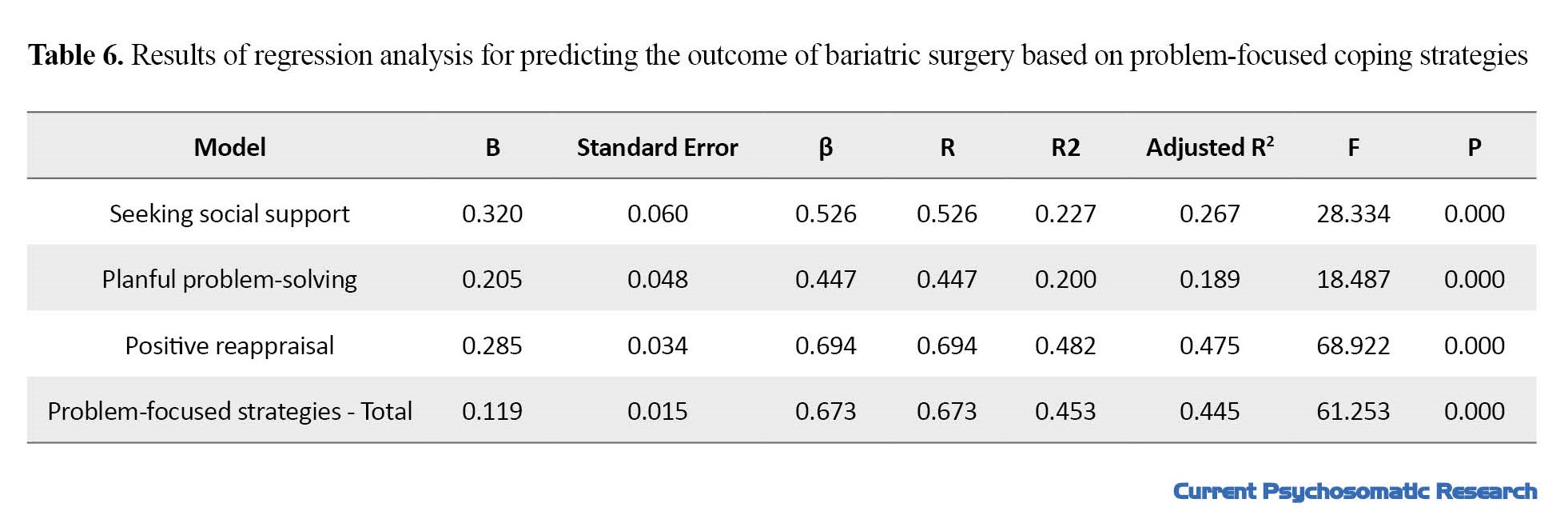

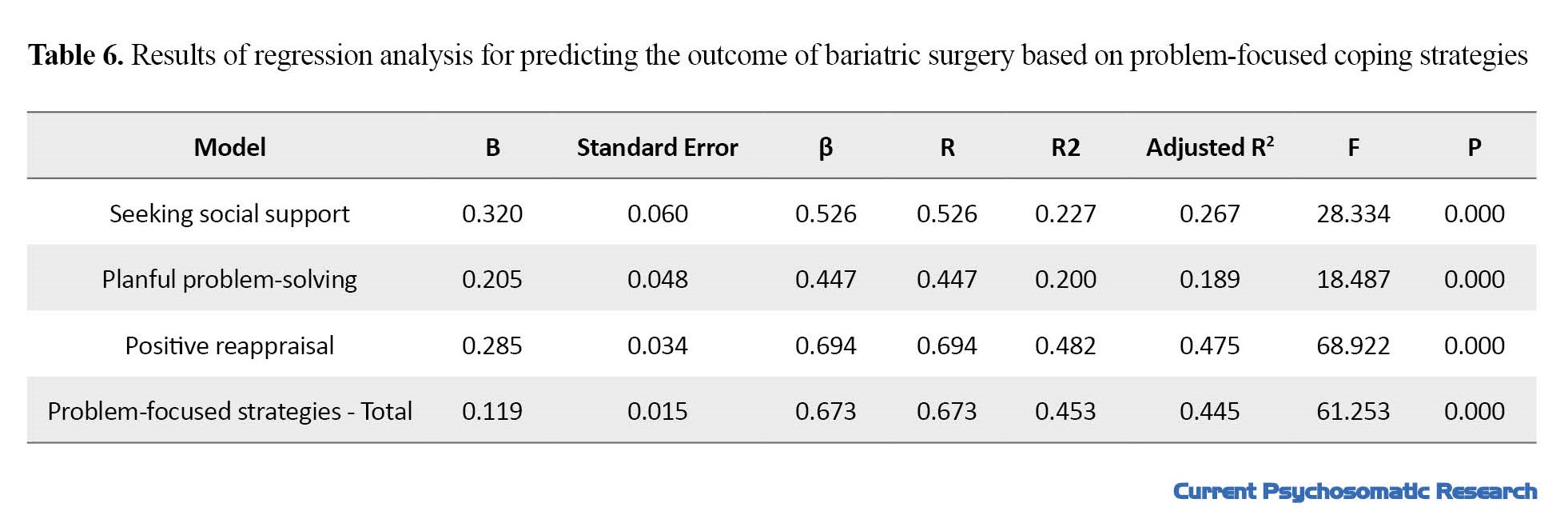

Multivariate regression analysis was used to examine the predictive power of problem-focused coping strategies. Based on the regression model, the scores of seeking social support, planful problem-solving, positive reappraisal, and the total score of problem-focused strategies could explain 26%, 18%, 47%, and 44% of the changes in the outcome of bariatric surgery, respectively (Table 6).

Discussion

According to the results, there was no significant relationship between the domains of emotion-focused coping strategies and the outcome of bariatric surgery; however, the domains of problem-focused strategies including seeking social support, planful problem-solving, positive reappraisal and the total score of problem-focused strategies had a positive relationship with the outcome of surgery. According to previous studies, stress can increase the likelihood of weight gain through biological and behavioral changes [20]. Therefore, psychological functions and coping strategies in response to stressful events could play a crucial role in weight loss maintenance [21]. In a study by Figura et al. on 64 patients with morbid obesity who were a candidate for bariatric surgery, the relationship between preoperative psychological issues including coping styles and the outcome of the surgery was examined in terms of excess weight loss. The results showed that patients with more active coping styles (i.e., active coping and planning) before surgery had higher excess weight loss after the surgery (60-115%). They concluded that active coping styles can be a predictive factor for the success of bariatric surgery [22].

One possible explanation is that problem-focused coping strategies may be associated with a higher level of awareness about bariatric surgery and its outcomes. For instance, those with problem-focused coping strategies tend to search on the internet, ask the peers with a history of surgery, and obtain information from doctors; therefore, they develop a more informed perspective on bariatric surgery. They understand that bariatric surgery is not enough and healthy lifestyle and weight control are also needed [23]. In addition, problem-focused coping strategies can help patients overcome the barriers to having a healthy lifestyle, manage daily stressors, and consequently have better adherence to postoperative dietary and exercise. Furthermore, healthy coping styles can improve interpersonal relationships and daily function [24], and increase psychological adjustment with post-operative changes. In contrast, the use of maladaptive coping styles is significantly associated with a higher rate of depression, anxiety, and emotional overeating, and a poor adherence to postoperative treatments [25]. The use of inefficient emotion-focused coping strategies can lead to increased stress and thus lead to unhealthy lifestyles. For instance, increased stress can lead to overeating, which is a risk factor for weight regain and treatment failure [26]. In fact, bad eating habits such as emotional eating and the use of maladaptive coping strategies can lead to negative emotions, body dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem which cause persistent engagement in bad eating habits, poor lifestyle, and obesity [13]. The guidelines for pre- and post-operative psychological assessments and interventions for bariatric surgery need to be improved by using the evidence-based approach [27]. Assessment of coping strategies before bariatric surgery should be considered as a crucial step.

As the limitations of this study, those with metabolic and hormonal disorders, major psychiatric disorders and eating disorders were excluded, and all candidates had surgery by one medical team and in one place and center. Moreover, life styles, daily physical activity, and family support factors were not evaluated in our study. These factors should be considered as confounding variables in future studies.

Conclusion

Problem-focused coping strategies can predict the outcome of bariatric surgery for treatment of obesity. Therefore, it is recommended that pre- and post-operative psychological support for obese people should focus on improving their problem-focused coping strategies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1398.515). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the study, and their information was kept confidential.

Funding

This paper was extracted from the thesis of Yasaman Zahedi, funded by Iran University of Medical Science.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and Supervision: Atefeh Ghanbari Jolfaei and Abdolreza Pazouki; Investigation, Writing original draft, review & editing: Yasaman Zahedi and Mohammad Pir Hayati; Data collection: Sara Nooraeen and Mohammad Pir Hayati; Data analysis: Mohammad Pir Hayati; Resources: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thea authors would like to thank all participants in this study for their cooperation.

References

Obesity is a chronic condition characterized by an increase in body fat. The body fat content can be measured by the body mass index (BMI) which is defined as the ratio of body weight (in kilograms) to body height (in meters squared). In clinical definition, a BMI of 25–29 kg/m2 indicates overweight and a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 is considered obesity. Obesity is a serious public health problem worldwide [1]. Excessive amount of body fat is usually caused by an imbalance between consuming calories and the energy intake [2]. Sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy diet are other factors that can lead to obesity. The global obesity prevalence has led to an alarming increase in mortality rate and associated complications. Obesity has also significant economic and psychological consequences. Evidence suggests an association between obesity and eating disorders (especially binge eating disorder), substance use disorders, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder [2-4].

Morbid obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) has become a major health problem in many countries [1]. This disorder is often resistant to dietary regimen or medications. It also has a low response to psychotherapy or other conventional interventions [3], but it has responded well to bariatric surgery [5]. This treatment method has a favorable short-term and long-term effect in controlling weight and obesity complications [6]. Studies have shown that bariatric surgery can reduce and maintain weight and improve other health conditions [7, 8, 9]. Although bariatric surgery is an effective treatment for obesity, it was shown that the psychological factors can affect its outcome [10]. There is a need to obtain information about the psychological predictors of obesity after surgery [11, 12]. Stress is one of the effective psychological factors, because stressful conditions can lead to dietary problems, lack of exercise, and difficulty regulating emotions, each of which is involved in the development and persistence of obesity [13].

In addition, Stress can alter eating patterns [14-16]. In stressful situations, people use different thoughts and behaviors called “coping strategies”. These strategies are divided into two main categories, problem-focused and emotion-focused. In problem-focused strategies, the individual uses active methods and directly takes action to solve the cause of the problem. In emotion-focused strategies, a person regulates his/her feelings and emotional responses to tolerate stress. Studies have also shown that successful weight maintenance is associated with better coping strategies and better ability to manage life stressors. Eating in response to negative emotions and stress are the factors that can increase the risk of weight regain after bariatric surgery [17]. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the relationship between coping strategies and the outcome of bariatric surgery. The results can help develop psychological interventions before and after bariatric surgery.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This prospective/observational study was conducted on 85 patients with morbid obesity who were candidates for bariatric surgery in two general hospitals (Hazrat-e Rasoul Akram and Milad) in Tehran, Iran, who were selected by a convenience sampling method. They had 18-66 years of age, referred to obesity clinics to receive bariatric surgery (gastric bypass or mini-gastric bypass). First, medical history was recorded and the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 was used to ensure that patients had no endocrine or psychiatric disorders. Those with metabolic or hormonal disorders, major psychiatric disorders, and eating disorders were excluded from study. All participants received surgery by one surgery team and in one place and center. Their lifestyle, daily exercises, and family support were not evaluated. Their BMI was measured and coping strategies were evaluated. After two years, the outcome of the surgery was assessed by the Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS). In addition, their BMI was recorded again. After two years, 76 (90%) patients agreed to continue the study and 9 (10%) left the study.

Instruments

A demographic checklist was used to survey the demographic characteristics including age, gender, marital status, and cigarette smoking. Coping strategies were evaluated using the 66-item ways of coping questionnaire developed by Folkman & Lazarus in 1988. This questionnaire measures two strategies of problem-focused and emotion-focused. The problem-focused dimension measures four characteristics include seeking social support, accepting responsibility, planful problem-solving, and positive reappraisal. The emotion-focused dimension measures four characteristics of confrontive coping, distancing, self-controlling, and escape-avoidance. Folkman & Lazarus reported the reliability of its subscales from 0.61 for coping to 0.79 for positive reappraisal. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this tool have been confirmed in Iran [18]. The BAROS was used to evaluate the success of bariatric surgery. This questionnaire has 6 questions measuring weight loss and medical conditions. The total score is 9; a score of 1 or less indicates failure, a score >1-3 shows a fair outcome, a score > 3-5 indicates a good outcome, a score >5-7 shows a very good outcome, and a score >7-9 shows an excellent outcome. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this tool have been confirmed in Iran [19].

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS software, version 23 for data analysis. Correlation test and regression analysis were used to analyze the data. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

The mean age of participants was 38.11±11.5 years. There were 18 males (23.7%) and 58 females (76.3%); 25% (n=19) were single and 75% (n=57) were married. In terms of cigarette smoking, 27.6% (n=21) had a positive history (Table 1).

The mean score of BAROS was 4.6±1.4. The frequency of outcomes were as follows: 1 (1.3%) failure, 8 (10.5%) acceptable, 36 (47.4%) good, 26 (34.2%) very good, and 5 (6.6%) excellent (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the scores of copying strategies.

The mean total score of problem-focused coping strategies was 89.35 and the mean total score of emotion-focused coping strategies was 59.35. Table 4 shows the correlation coefficients between the domains of coping strategies and the outcome of surgery.

Table 5 presents the correlation coefficients between demographic factors and the surgery outcome.

Multivariate regression analysis was used to examine the predictive power of problem-focused coping strategies. Based on the regression model, the scores of seeking social support, planful problem-solving, positive reappraisal, and the total score of problem-focused strategies could explain 26%, 18%, 47%, and 44% of the changes in the outcome of bariatric surgery, respectively (Table 6).

Discussion

According to the results, there was no significant relationship between the domains of emotion-focused coping strategies and the outcome of bariatric surgery; however, the domains of problem-focused strategies including seeking social support, planful problem-solving, positive reappraisal and the total score of problem-focused strategies had a positive relationship with the outcome of surgery. According to previous studies, stress can increase the likelihood of weight gain through biological and behavioral changes [20]. Therefore, psychological functions and coping strategies in response to stressful events could play a crucial role in weight loss maintenance [21]. In a study by Figura et al. on 64 patients with morbid obesity who were a candidate for bariatric surgery, the relationship between preoperative psychological issues including coping styles and the outcome of the surgery was examined in terms of excess weight loss. The results showed that patients with more active coping styles (i.e., active coping and planning) before surgery had higher excess weight loss after the surgery (60-115%). They concluded that active coping styles can be a predictive factor for the success of bariatric surgery [22].

One possible explanation is that problem-focused coping strategies may be associated with a higher level of awareness about bariatric surgery and its outcomes. For instance, those with problem-focused coping strategies tend to search on the internet, ask the peers with a history of surgery, and obtain information from doctors; therefore, they develop a more informed perspective on bariatric surgery. They understand that bariatric surgery is not enough and healthy lifestyle and weight control are also needed [23]. In addition, problem-focused coping strategies can help patients overcome the barriers to having a healthy lifestyle, manage daily stressors, and consequently have better adherence to postoperative dietary and exercise. Furthermore, healthy coping styles can improve interpersonal relationships and daily function [24], and increase psychological adjustment with post-operative changes. In contrast, the use of maladaptive coping styles is significantly associated with a higher rate of depression, anxiety, and emotional overeating, and a poor adherence to postoperative treatments [25]. The use of inefficient emotion-focused coping strategies can lead to increased stress and thus lead to unhealthy lifestyles. For instance, increased stress can lead to overeating, which is a risk factor for weight regain and treatment failure [26]. In fact, bad eating habits such as emotional eating and the use of maladaptive coping strategies can lead to negative emotions, body dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem which cause persistent engagement in bad eating habits, poor lifestyle, and obesity [13]. The guidelines for pre- and post-operative psychological assessments and interventions for bariatric surgery need to be improved by using the evidence-based approach [27]. Assessment of coping strategies before bariatric surgery should be considered as a crucial step.

As the limitations of this study, those with metabolic and hormonal disorders, major psychiatric disorders and eating disorders were excluded, and all candidates had surgery by one medical team and in one place and center. Moreover, life styles, daily physical activity, and family support factors were not evaluated in our study. These factors should be considered as confounding variables in future studies.

Conclusion

Problem-focused coping strategies can predict the outcome of bariatric surgery for treatment of obesity. Therefore, it is recommended that pre- and post-operative psychological support for obese people should focus on improving their problem-focused coping strategies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1398.515). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the study, and their information was kept confidential.

Funding

This paper was extracted from the thesis of Yasaman Zahedi, funded by Iran University of Medical Science.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and Supervision: Atefeh Ghanbari Jolfaei and Abdolreza Pazouki; Investigation, Writing original draft, review & editing: Yasaman Zahedi and Mohammad Pir Hayati; Data collection: Sara Nooraeen and Mohammad Pir Hayati; Data analysis: Mohammad Pir Hayati; Resources: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thea authors would like to thank all participants in this study for their cooperation.

References

- Ristanto A, Caltabiano ML. Psychological support and well-being in post-bariatric surgery patients. Obes Surg. 2019; 29(2):739-43. [DOI:10.1007/s11695-018-3599-8] [PMID]

- Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, MacInnis RJ, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363(23):2211-9. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1000367] [PMID]

- Amann B, Mergl R, Torrent C, Perugi G, Padberg F, El-Gjamal N, et al. Abnormal temperament in patients with morbid obesity seeking surgical treatment. J Affect Disord. 2009; 118(1-3):155-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.020] [PMID]

- Pavan C, Azzi M, Lancerotto L, Marini M, Busetto L, Bassetto F, et al. Overweight/obese patients referring to plastic surgery: Temperament and personality traits. Obes Surg. 2013; 23(4):437-45. [DOI:10.1007/s11695-012-0769-y] [PMID]

- van Hout GC, Vreeswijk CM, van Heck GL. Bariatric surgery and bariatric psychology: Evolution of the Dutch approach. Obes Surg. 2008; 18(3):321-5. [DOI:10.1007/s11695-007-9271-3] [PMID]

- Yeoh YS, Koh GC, Tan CS, Lee KE, Tu TM, Singh R, et al. Can acute clinical outcomes predict health-related quality of life after stroke: A one-year prospective study of stroke survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018; 16(1):221. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-018-1043-3] [PMID]

- Trakhtenbroit MA, Leichman JG, Algahim MF, Miller CC 3rd, Moody FG, Lux TR, et al. Body weight, insulin resistance, and serum adipokine levels 2 years after 2 types of bariatric surgery. Am J Med. 2009; 122(5):435-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.10.035] [PMID]

- Doumouras AG, Wong JA, Paterson JM, Lee Y, Sivapathasundaram B, Tarride JE, et al. Bariatric surgery and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with obesity and cardiovascular disease: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Circulation. 2021; 143(15):1468-80. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052386] [PMID]

- Aminian A, Al-Kurd A, Wilson R, Bena J, Fayazzadeh H, Singh T, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with major adverse liver and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. JAMA. 2021; 326(20):2031-42. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2021.19569] [PMID]

- Reaves DL, Dickson JM, Halford JCG, Christiansen P, Hardman CA. A qualitative analysis of problematic and non-problematic alcohol use after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2019; 29(7):2200-9. [DOI:10.1007/s11695-019-03823-6] [PMID]

- Pull CB. Current psychological assessment practices in obesity surgery programs: What to assess and why. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010; 23(1):30-6. [DOI:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328334c817]

- Kayman S, Bruvold W, Stern JS. Maintenance and relapse after weight loss in women: Behavioral aspects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990; 52(5):800-7. [DOI:10.1093/ajcn/52.5.800] [PMID]

- Farahmand H, Pourhosein R, Hashemi Najafabadi SA. [A review and meta-analysis of the relationship between stress and obesity (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi J. 2019; 7(12):163-82. [Link]

- Klatzkin RR, Baldassaro A, Rashid S. Physiological responses to acute stress and the drive to eat: The impact of perceived life stress. Appetite. 2019; 133:393-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2018.11.019] [PMID]

- van der Valk ES, Savas M, van Rossum EFC. Stress and obesity: Are there more susceptible individuals? Curr Obes Rep. 2018; 7(2):193-203. [DOI:10.1007/s13679-018-0306-y] [PMID]

- Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol Behav. 2007; 91(4):449-58. [DOI:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011] [PMID]

- Elfhag K, Rössner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005; 6(1):67-85. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x] [PMID]

- Niknami M, Dehghani F, Bouraki S, Kazem Nejad Leili E, Soleimani R. [Strategies among students of Guilan university of medical sciences (Persian)]. J Holistic Nurs Midwifery. 2014; 24(4):62-8. [Link]

- Ahmadzad-Asl M, Dinarvand B, Bodaghi F, Shariat SV, Sabzvari Z, Talebi M, et al. Changes in cognition functions and depression severity after bariatric surgery: A 3-month follow-up study. Iran J Psychiatry BehavSci. 2022; 16(2):e113421. [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs-113421]

- Sominsky L, Spencer SJ. Eating behavior and stress: A pathway to obesity. Front Psychol. 2014; 5:434. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00434] [PMID]

- Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Brownell, Confronting and coping with weight stigma: An investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity. 2006; 14(10):1802-15. [DOI:10.1038/oby.2006.208] [PMID]

- Figura A, Ahnis A, Stengel A, Hofmann T, Elbelt U, Ordemann J, et al. Determinants of weight loss following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: The role of psychological burden, coping style, and motivation to undergo surgery. J Obes. 2015; 2015:626010.[DOI:10.1155/2015/626010] [PMID]

- White MA, Kalarchian MA, Masheb RM, Marcus MD, Grilo CM. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery patients: A prospective, 24-month follow-up study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009; 70(2):10844. [Link]

- Stanisławski K. The coping circumplex model: An integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Front Psychol. 2019; 0:694. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00694] [PMID]

- Fettich KC, Chen EY. Coping with obesity stigma affects depressed mood in African‐American and white candidates for bariatric surgery. Obesity. 2012; 20(5):1118-21. [DOI:10.1038/oby.2012.12] [PMID]

- Rydén A, Karlsson J, Persson LO, Sjöström L, Taft C, Sullivan M. Obesity‐related coping and distress and relationship to treatment preference. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001; 40(2):177-88. [DOI:10.1348/014466501163625] [PMID]

- Rutledge T, Ellison JK, Phillips AS. Revising the bariatric psychological evaluation to improve clinical and research utility. J Behav Med. 2020; 43(4):660-5. [DOI:10.1007/s10865-019-00060-1] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2023/05/21 | Accepted: 2023/07/1 | Published: 2023/07/1

Received: 2023/05/21 | Accepted: 2023/07/1 | Published: 2023/07/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |