Thu, May 22, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 1, Issue 3 (Spring 2023)

CPR 2023, 1(3): 316-331 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bayani M A, Nekoofar N, Bijani A, Moudi S. Comparison of Glucose Control Profile in Patients With Depression and Type 2 Diabetes Receiving Bupropion or Venlafaxine: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. CPR 2023; 1 (3) :316-331

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-55-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-55-en.html

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1940 kb]

(306 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1250 Views)

Full-Text: (340 Views)

Introduction

Depression is a common comorbidity in patients with diabetes mellitus. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed the prevalence of depression in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) as 19%, 1.76 times higher than that of those without diabetes. The prevalence of T2D is higher in low- and middle-income countries than high-income countries [1]. Multiple biological, social, mental, and lifestyle factors have been reported to be related to depression in diabetic patients [2], which can warn specialists to apply different treatment approaches to achieve better clinical outcomes and improve the quality of life in diabetic patients with depression [3, 4]. Comorbidity of depression and diabetes can be associated with serious vascular complications, deteriorated adherence to treatment, lower quality of life, more hospitalization, higher health expenditure, and increased mortality [5, 6]. A variety of pharmacological and/or psychological interventions have been recommended for the treatment of depression in diabetic patients; however, given the interference of some antidepressants with glucose metabolism, the impact, tolerability, safety, and side effects of different interventions should be evaluated in various populations [4, 7].

Considering undesirable side effects, especially on the glycemic profile, a few antidepressant medications have been proposed for treatment of depression in patients with diabetes [7]. Bupropion, as a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, is one of the effective antidepressants in patients with diabetes [8, 9, 10]. Venlafaxine, as a mixed serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is another antidepressant that binds and blocks both the serotonin and norepinephrine transporters. Although this drug has been introduced as one of the most effective treatments in patients with depression [11], the findings of a study examining the efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in patients with comorbid depression and diabetes were not conclusive [7]. A meta-analysis that compared 21 antidepressants for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder reported the odds ratio for efficacy (1.78; 95% CI:1.61-1.96) and acceptability (1.04; 0.95-1.15) of venlafaxine, and for efficacy (1.58, 95% CI:1.35–1.86) and acceptability (0.96, 95% CI: 0.81–1.14) of bupropion [12]. Since limited clinical trials compared the therapeutic impact and unwanted side effects of bupropion and venlafaxine in patients with depression and T2D, this study aims to compare them.

Materials and Method

Trial design and participants

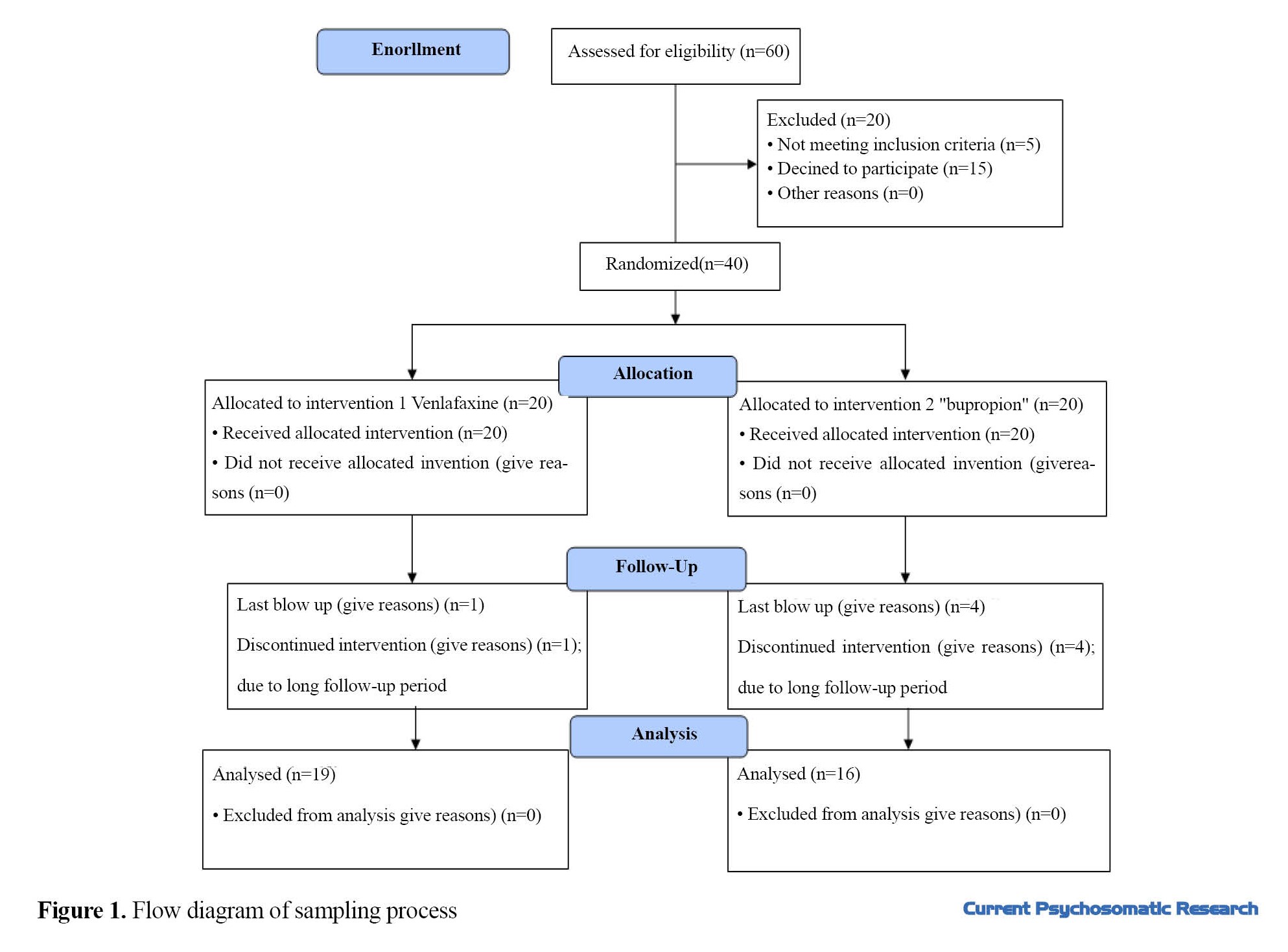

This randomized controlled clinical trial was carried out on adult patients with T2D referred to the endocrinology clinic of a government hospital in Babol, north of Iran. Among these patients, those with depression (depressive spectrum) diagnosed by a psychiatrist were selected by a convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria were age 18 years and above, having T2D confirmed by an endocrinologist, and having depression based on a clinical interview. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or breastfeeding, migrating during the study, and having uncontrolled cardiovascular or ocular diseases. Considering a test power of 0.80, 95% confidence level, and 0.5 unit of difference in HbA1c between two groups after treatment protocol, and taking into account a drop-out rate of 20% at the end of 12-week follow-up period, the sample size was 20 in each group (Total= 40). The participants were allocated randomly into two groups: intervention group (Venlafaxine) and control group (Bupropione) using a random number table. The flowchart of sampling process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Interventions

The first group received 37.5-150 mg venlafaxine (Abidi Pharmacutical Company, Iran) daily, while the second group was treated with 75-300 mg bupropion (Abidi Pharmacutical Company, Iran) daily. Both groups received the tablet forms of venlafaxine and bupropion. In the first group, first 37.5 mg (one tablet) venlafaxine was administered daily, which was gradually increased up to 150 mg/day, depending on the patient´s response (alleviation of depressive symptoms) while the patient was visited for follow-up (every four weeks). In the second group, bupropion was initiated with 75 mg (one tablet) per day, and increased up to 300 mg/day based on the patient´s clinical response to the prescribed drug regimen. Both groups were under treatment for 12 weeks. The appearance of bupropion and venlafaxine drug in two groups were similar to each other (white round tablets). The patients did not know which of the two drugs they were receiving; however, the clinician was aware of the type of treatment. Also, to examine the laboratory findings (blood glucose control and lipid profile), the laboratory staff did not know the allocation. The patients were visited every 4 weeks for 3 months; in each visit, physical and laboratory examinations were performed again, and severity of depressive symptoms were assessed. In addition, the occurrence of drug side effects was surveyed.

Measures

At first, after obtaining informed consent, baseline information including demographic characteristics (age, gender, level of education, occupation, marital status, living condition, and place of residence), duration of diabetes, co-morbidities, and the used medications were recorded. Assessment of height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) was performed. The initial examination was performed by a medical student. The presence of depressive symptoms was assessed with the 21-item Beck depression inventory (BDI), and persons who had these symptoms were referred to the psychiatrist for clinical interview. Laboratory tests were carried out to measure fasting plasma glucose, two-hour postprandial blood sugar (2hpp BS), HbA1C level, and serum lipid profile (triglyceride, total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ). All these tests were carried out in a specified laboratory at baseline and 12 weeks after.

The primary outcomes were severity of depressive symptoms (based on the BDI score, fasting blood sugar, 2hpp BS, and HbA1C). The secondary outcomes were serum lipid profile (triglyceride, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol), and self-reported adverse reactions to the prescribed drugs. The research outcomes were evaluated every four weeks.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed in SPSS software, version 17. Chi-square, t-test, paired t-test, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were used for data analysis. Per-protocol analysis was performed to compare the research outcomes between two groups. P-value less than 0.05 was considered as the significant level.

Results

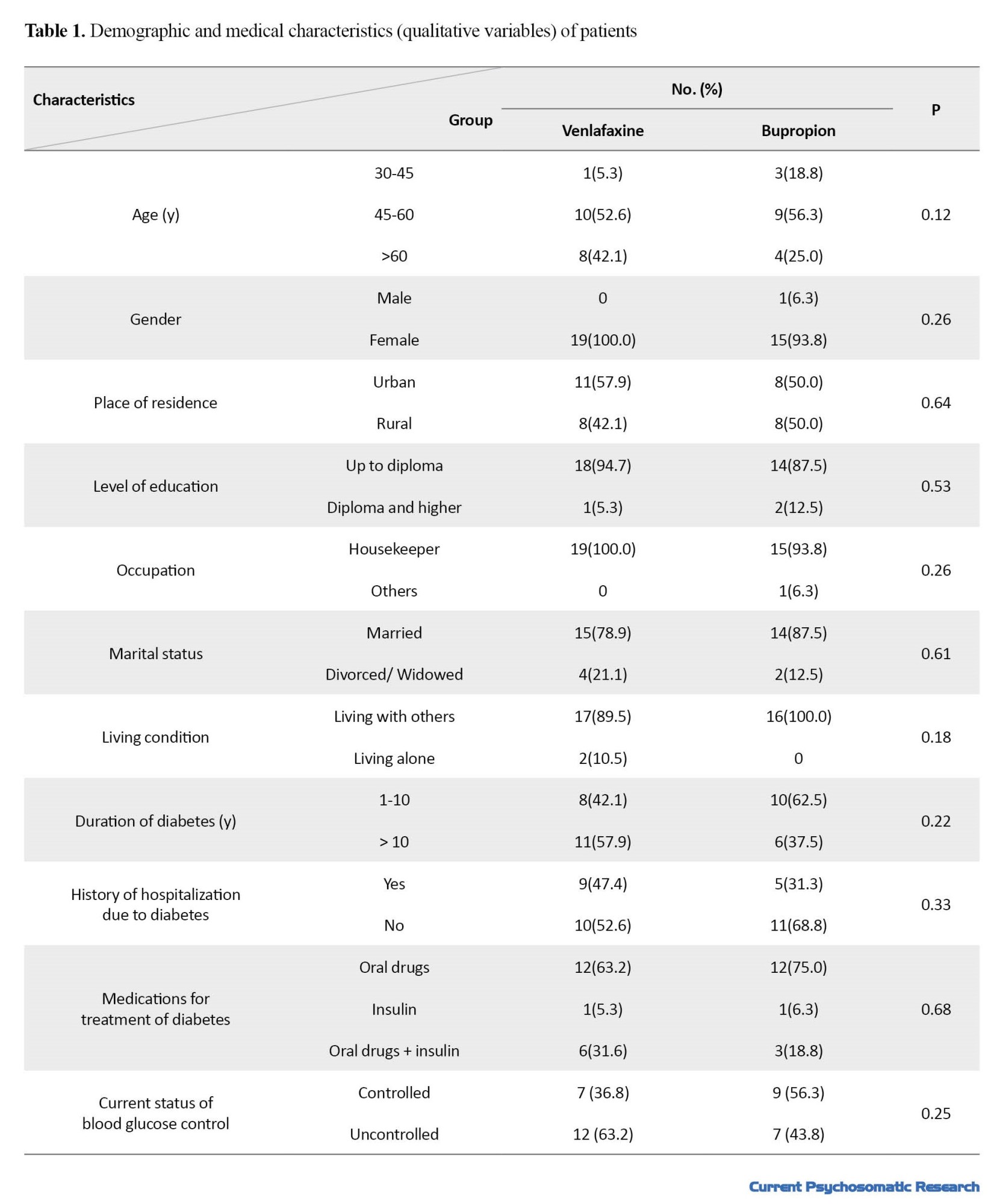

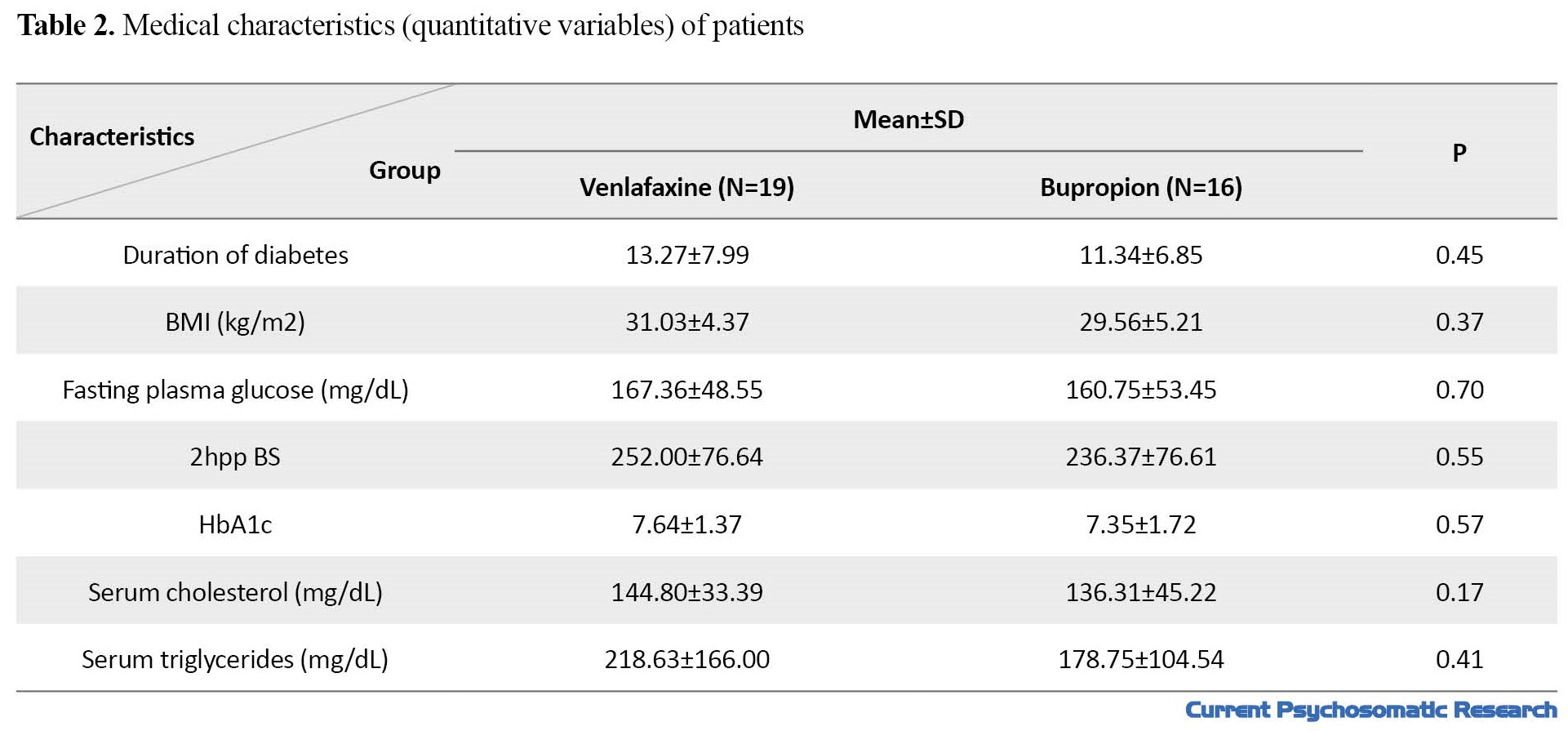

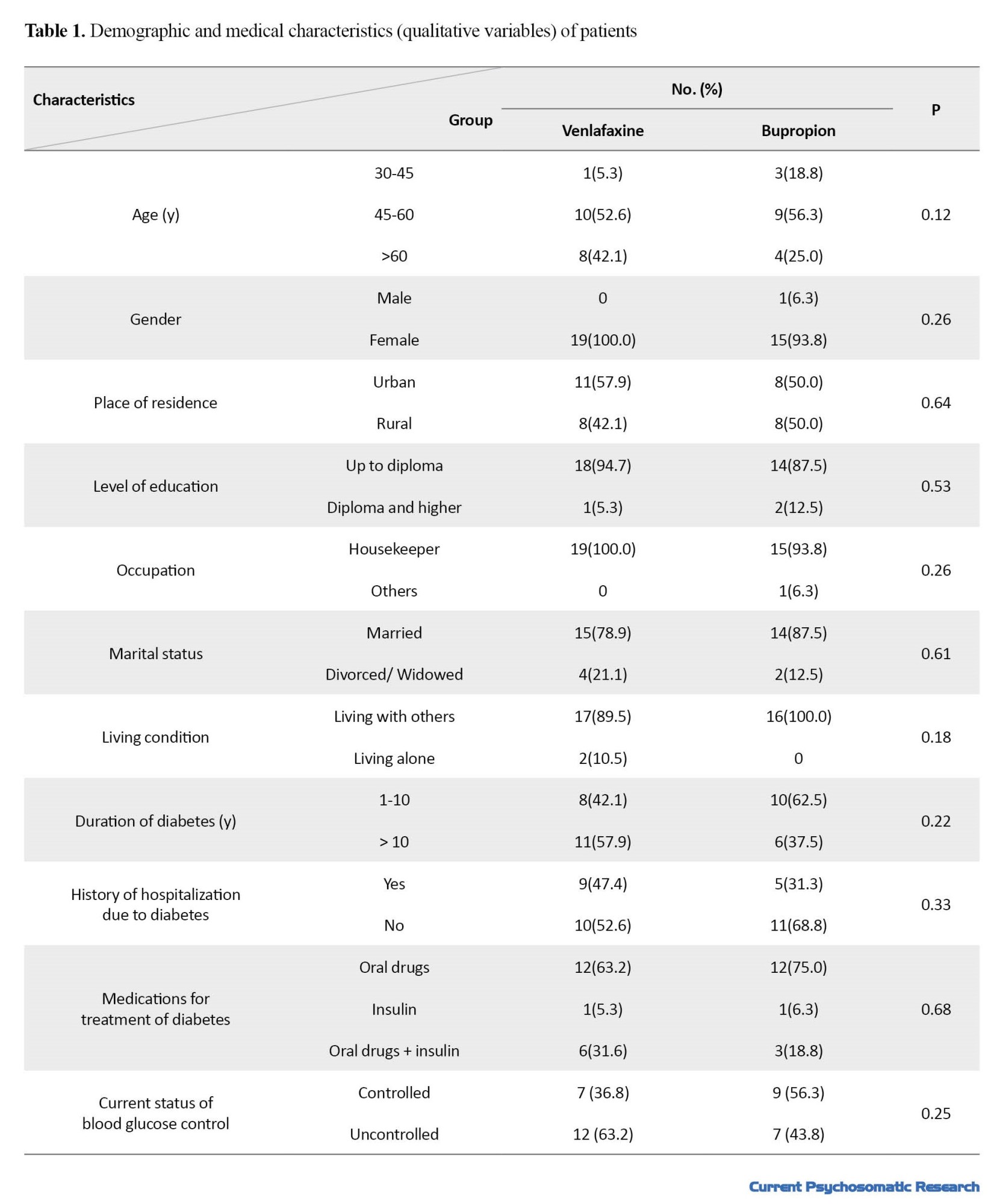

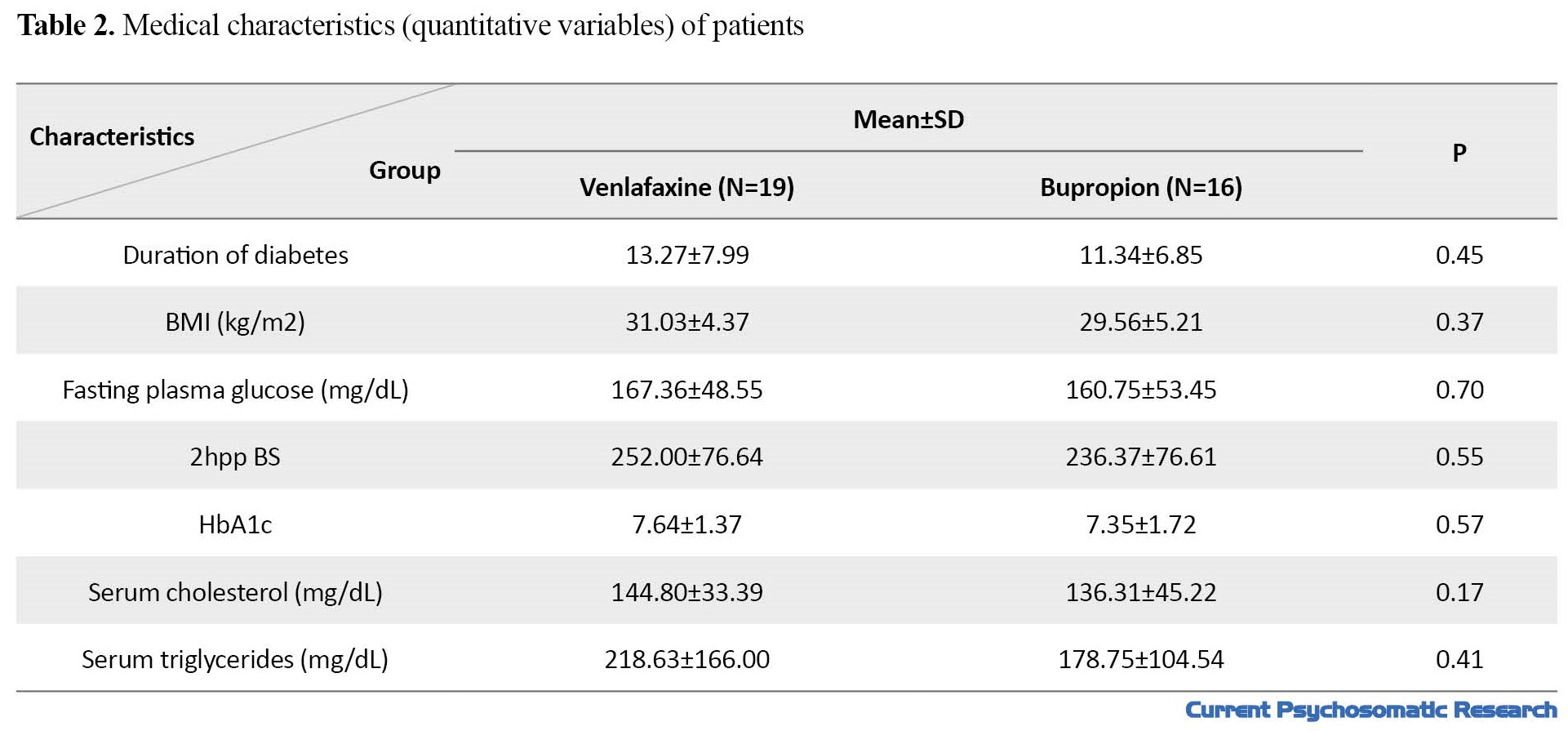

A total of 35 patients with T2D and depression completed the study. Baseline information for the two study groups are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

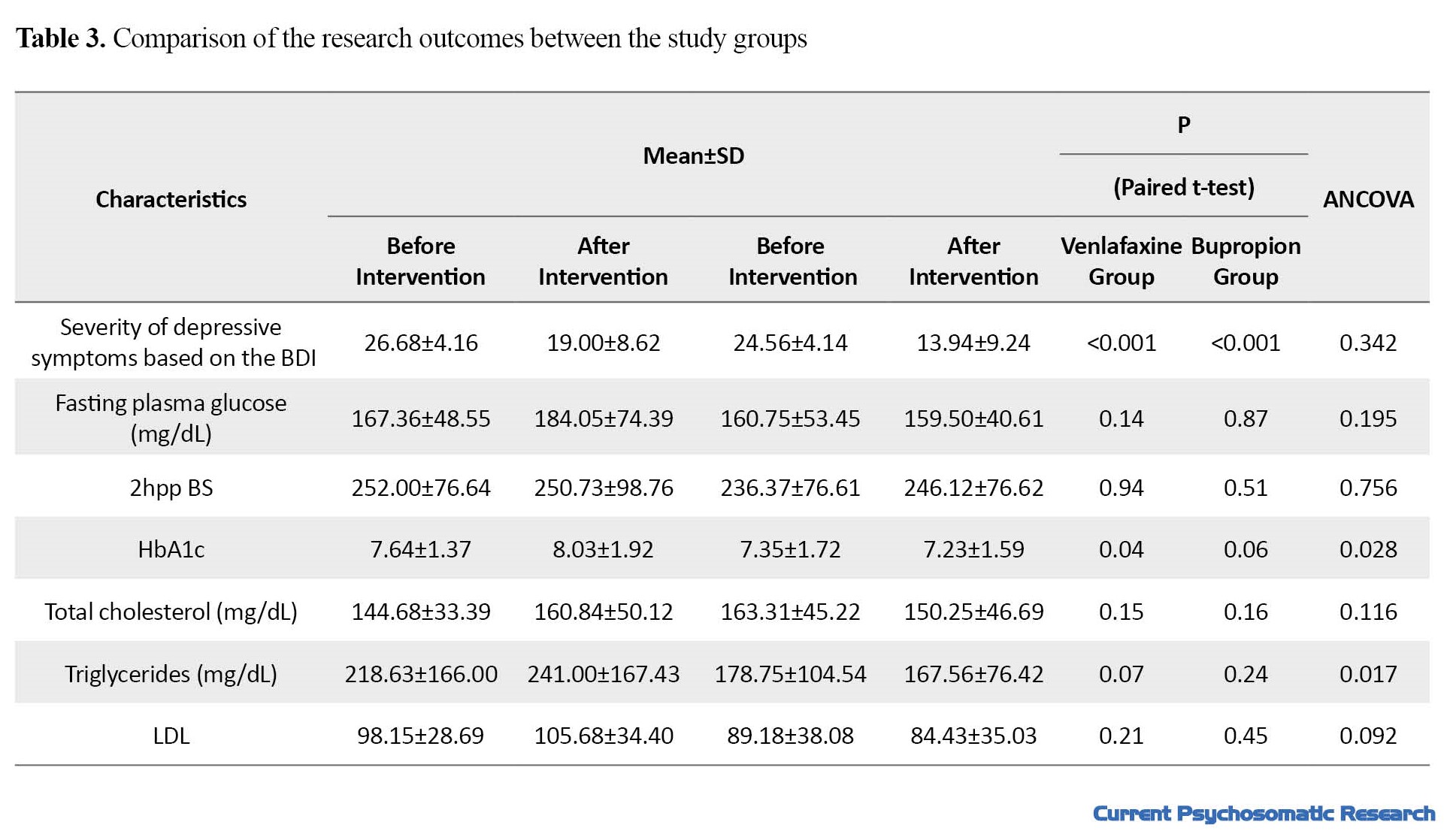

The study groups were not significantly different in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics (P>0.05). Mean age in venlafaxine and bupropion groups were 58.37±7.95 and 53.56±9.97 years, respectively (P=0.12). Comparison of the research outcomes between the two groups is presented in Table 3.

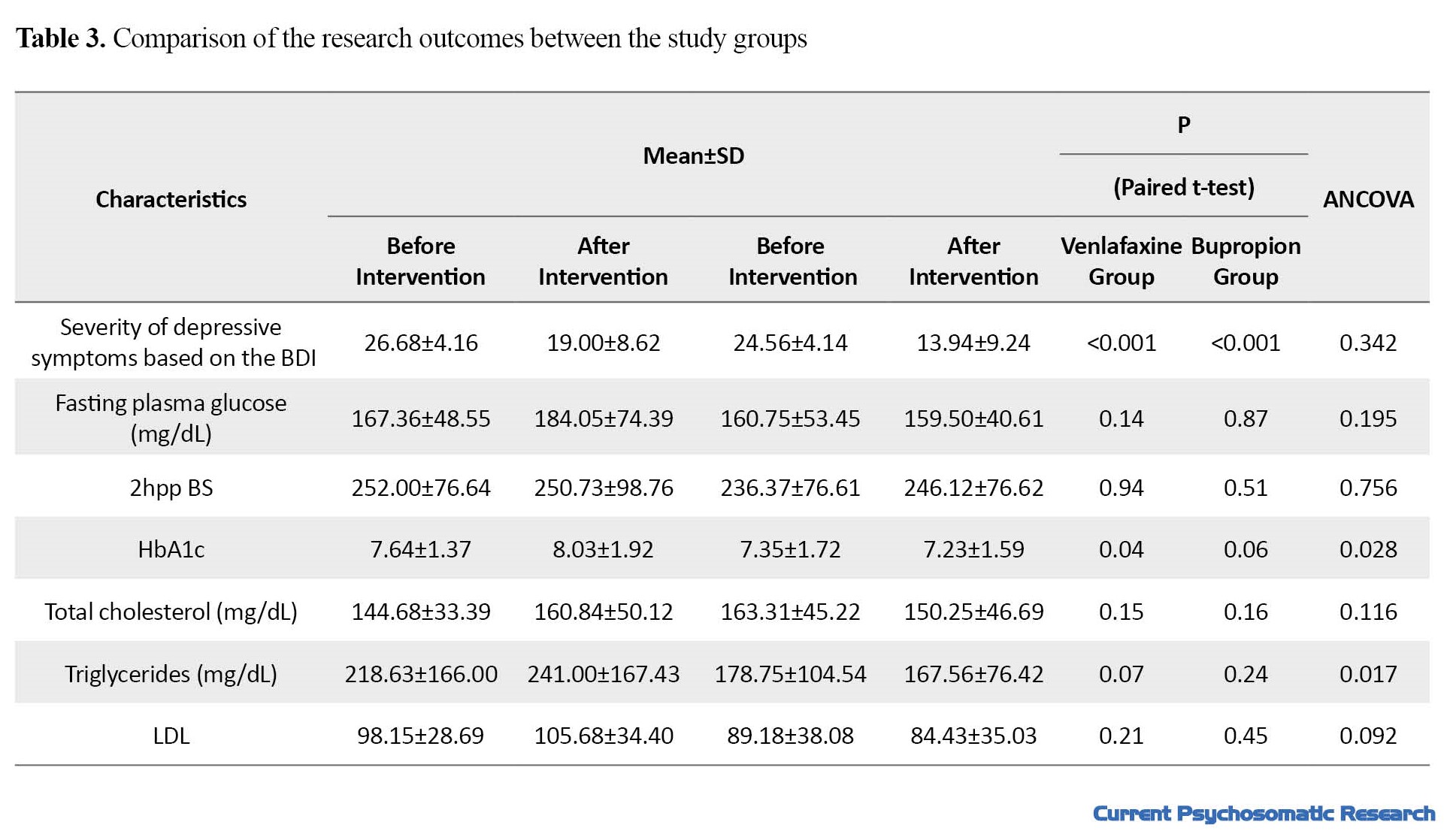

There was a significant decrease in depressive symptoms in both venlafaxine and bupropion groups; however, no statistically significant difference was found between them (P=0.342). The mean BMI in the venlafaxine group increased significantly (P=0.01), while the bupropion group showed a slightly decrease (P=0.10). These changes between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.003).

Fasting plasma glucose level in the venlafaxine group before and after the intervention was 167.36 and 184.05 mg/dL, respectively (P=0.14), while these values in the bupropion group were 160.75 and 159.50 mg/dL, respectively (P=0.87). It means that venlafaxine, unlike bupropion, increased fasting blood sugar, although these changes were not statistically significant. Furthermore, changes in fasting blood sugar between the two groups did not show a statistically significant difference, either (P=0.195).

The 2hpp BS before and after the intervention in the venlafaxine group was 252.00 and 250.73 mg/dL, respectively. In the group received bupropion, these values were 236.37 and 246.12 mg/dL, respectively. This shows that venlafaxine caused a slight decrease and bupropion caused an increase in 2hpp BS, these changes not statistically significant. The difference in 2hpp BS between the two groups was not statistically significant, either (P=0.756).

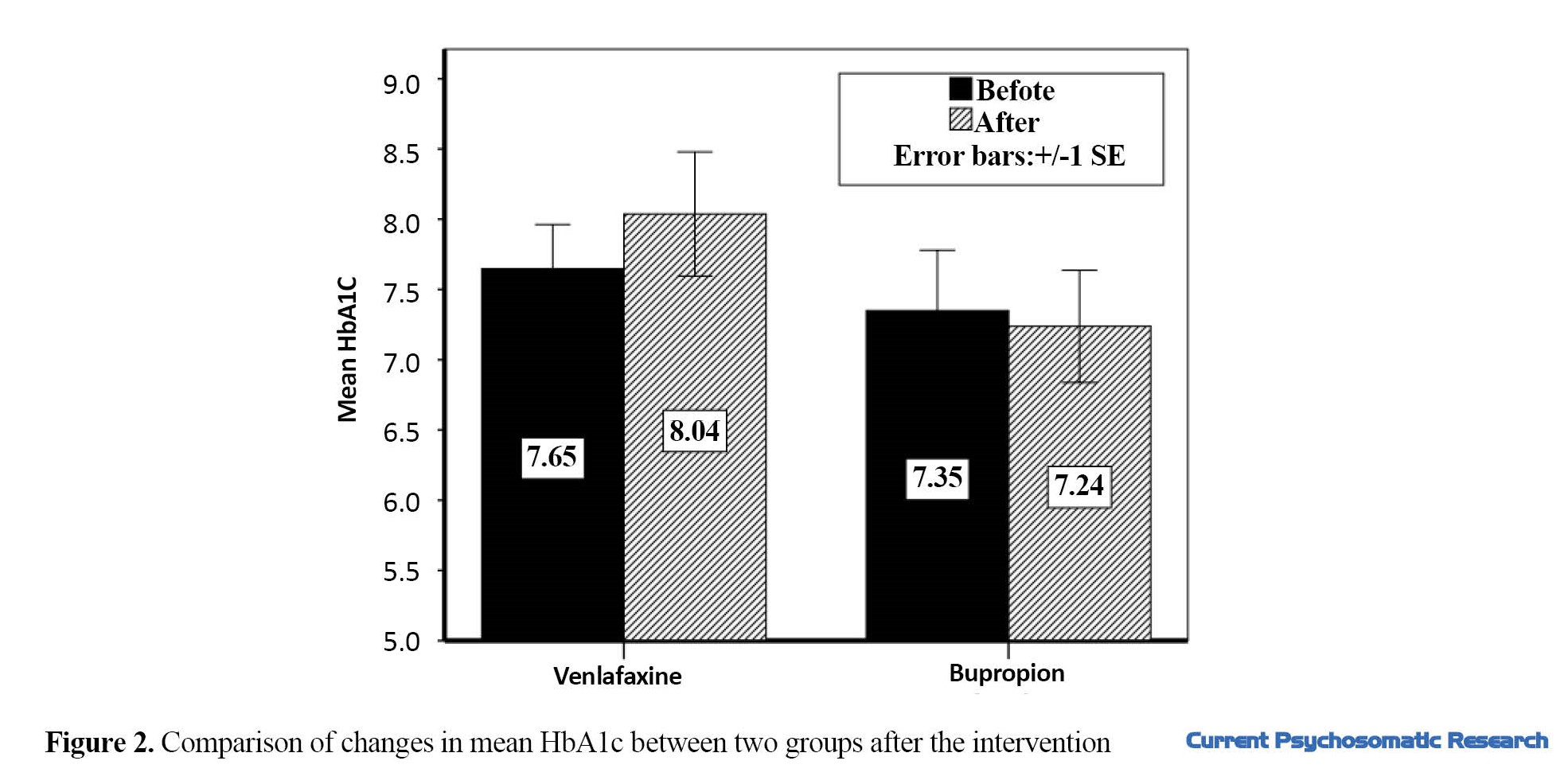

Venlafaxine caused a significant increase in HbA1c from 7.64 to 8.03 (P=0.04), and this value showed a decrease from 7.35 to 7.23 in the group received bupropion (P=0.06). The difference in HbA1c level was also significant between the two groups (P=0.028) (Figure 2). The results showed that venlafaxine administration changed the serum concentration of triglyceride (TG) from 218.63 to 241.00 mg/dL (P=0.07), while bupropion changed its level from 178.75 to 167.56 mg/dL (P=0.24). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.017). In the serum levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and total cholesterol, bupropion caused a slight decrease, while venlafaxine increased them; however, the difference between pretest and posttest levels and the difference between the two groups were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

The most common side effects reported for the two drugs, especially during the first weeks of treatment, were anxiety, nausea, and headache in the bupropion group, and nausea, insomnia, and loss of appetite in the venlafaxine group.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the therapeutic effects as well as adverse side-effects of bupropion and venlafaxine in patients with depression and T2D. The results showed the significant effect of both venlafaxine and bupropion on depressive symptoms. Although this effect was significant in both groups, no statistically significant decrease was observed between the two groups. Since the studies on comparing the effects of these two drugs are very limited [13], it was difficult to compare the findings of this research with their findings. A systematic review study on the effect of different antidepressants in patients with comorbid diabetes and depression demonstrated the positive effect of SSRIs, agomelatine, and bupropion on depressive symptoms in acute and maintenance phases and also on glycemic control [14]. Another review study suggested the SSRIs and bupropion as effective pharmacological interventions to improve depressive symptoms and prevent the recurrence of depression in patients with diabetes; furthermore, they showed the positive effect of SSRIs and bupropion on glycemic control of these individuals [15]. Gagnon et al. compared the effects of five antidepressants including citalopram, escitalopram, amitriptyline, venlafaxine, and trazodone on serum level of HbA1c in patients with diabetes, and reported better clinical outcomes for venlafaxine, amitriptyline, escitalopram and trazodone in comparison with citalopram [7].

In this study, glycemic profile showed heterogeneous changes following the drug interventions. Fasting plasma glucose level decreased in the bupropion group, but this change was not significant. In the venlafaxine group, fasting plasma glucose increased after the drug intervention, but the change was not significant, either. A significant change was observed in both groups in HbA1c; it decreased in the bupropion group, but increased in the venlafaxine group. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials for comparison of glycemic control following short-term (8-24 weeks) administration of different antidepressants in patients with T2D revealed the highest HbA1c reduction after taking vortioxetine, escitalopram and agomelatine [16]. In this review study, the clinical trials with administration of bupropion or venlafaxine were included in the review; therefore, we could not compare our findings with theirs. Several studies have reported SSRIs as effective drugs for glycemic control of patients with comorbid T2D and depression [16, 17]; however, there are limited clinical trials on the effect of bupropion and venlafaxine on the glycemic control.

In our study, the change in serum lipid profile was different between the two study groups. serum cholesterol, TG and LDL cholesterol decreased in the bupropion group, but increased in the venlafaxine group. Several studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of different antidepressants on lipid biomarkers [18]; however, the studies on diabetic patients comparing the antidepressant effects of bupropion and venlafaxine are limited. Some pathophysiological pathways involved in depression, such as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, change in circulating catecholamines and serum cortisol, and subsequently lipid disorder might be the reasons for the increase in lipid profile. Furthermore, antidepressants and dietary regimens can affect lipid biomarkers in these patients [13].

Another finding of this study was the effects of bupropion and venlafaxine on BMI; the venlafaxine group had a significant weight gain, but the bupropion group showed a slightly decrease in BMI. Uguz et al. also reported a significant weight gain following the administration of venlafaxine [19]. Gill et al. also showed the effect of bupropion on reducing weight [20]. Evidence suggests the role of serotonin and histamine off-target appetite-promoting pathways in adverse weight-gain effects of antidepressants [20].

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study that compares different clinical effects of venlafaxine and bupropion in patients with T2D and depression. However, there were some limitations and disadvantages such as non-completion of treatment course in some patients, not considering the presence of simultaneous stressors that can affect the patients´ mood such as financial and family problems, and not considering the dosage of medications used to control diabetes (oral medication or insulin) during the 12-week follow-up period. In addition, the study scale was a self-report tool, which can affect the research findings. Studies with large sample size and longer duration of follow-up, using structured interviews for evaluation of depressive symptoms are recommended.

Conclusion

Although venlafaxine can reduce depression, it is not suggested as a proper drug for treatment of depression in people with T2D due to its adverse effects on glycemic control, lipid profile and weight of the patients. However, bupropion can be considered as a treatment choice for patients with comorbid T2D and depression, due to favorable effects on depressive symptoms, weight reduction, glycemic control, and having low side effects,

Data availability statement

The data will be available for academic researchers with sending an email to the corresponding author (sussan.mouodi@gmail.com).

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All participants signed a written informed consent prior to the study. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Babol University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUBABOL.HRI.REC.1397.094). The study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20150630022991N12; available at https://en.irct.ir/trial/32944).

Funding

This study was financially supported by Babol University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and design: Mohammad Ali Bayani, Nikta Nekoofar, and Sussan Moudi; supervision: Mohammad Ali Bayani and Sussan Moudi; Data collection, data analysis, preparing initial draft, review, and approval of final draft: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Babol University of Medical Sciences for their financial support.

References

Depression is a common comorbidity in patients with diabetes mellitus. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed the prevalence of depression in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) as 19%, 1.76 times higher than that of those without diabetes. The prevalence of T2D is higher in low- and middle-income countries than high-income countries [1]. Multiple biological, social, mental, and lifestyle factors have been reported to be related to depression in diabetic patients [2], which can warn specialists to apply different treatment approaches to achieve better clinical outcomes and improve the quality of life in diabetic patients with depression [3, 4]. Comorbidity of depression and diabetes can be associated with serious vascular complications, deteriorated adherence to treatment, lower quality of life, more hospitalization, higher health expenditure, and increased mortality [5, 6]. A variety of pharmacological and/or psychological interventions have been recommended for the treatment of depression in diabetic patients; however, given the interference of some antidepressants with glucose metabolism, the impact, tolerability, safety, and side effects of different interventions should be evaluated in various populations [4, 7].

Considering undesirable side effects, especially on the glycemic profile, a few antidepressant medications have been proposed for treatment of depression in patients with diabetes [7]. Bupropion, as a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, is one of the effective antidepressants in patients with diabetes [8, 9, 10]. Venlafaxine, as a mixed serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is another antidepressant that binds and blocks both the serotonin and norepinephrine transporters. Although this drug has been introduced as one of the most effective treatments in patients with depression [11], the findings of a study examining the efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in patients with comorbid depression and diabetes were not conclusive [7]. A meta-analysis that compared 21 antidepressants for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder reported the odds ratio for efficacy (1.78; 95% CI:1.61-1.96) and acceptability (1.04; 0.95-1.15) of venlafaxine, and for efficacy (1.58, 95% CI:1.35–1.86) and acceptability (0.96, 95% CI: 0.81–1.14) of bupropion [12]. Since limited clinical trials compared the therapeutic impact and unwanted side effects of bupropion and venlafaxine in patients with depression and T2D, this study aims to compare them.

Materials and Method

Trial design and participants

This randomized controlled clinical trial was carried out on adult patients with T2D referred to the endocrinology clinic of a government hospital in Babol, north of Iran. Among these patients, those with depression (depressive spectrum) diagnosed by a psychiatrist were selected by a convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria were age 18 years and above, having T2D confirmed by an endocrinologist, and having depression based on a clinical interview. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or breastfeeding, migrating during the study, and having uncontrolled cardiovascular or ocular diseases. Considering a test power of 0.80, 95% confidence level, and 0.5 unit of difference in HbA1c between two groups after treatment protocol, and taking into account a drop-out rate of 20% at the end of 12-week follow-up period, the sample size was 20 in each group (Total= 40). The participants were allocated randomly into two groups: intervention group (Venlafaxine) and control group (Bupropione) using a random number table. The flowchart of sampling process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Interventions

The first group received 37.5-150 mg venlafaxine (Abidi Pharmacutical Company, Iran) daily, while the second group was treated with 75-300 mg bupropion (Abidi Pharmacutical Company, Iran) daily. Both groups received the tablet forms of venlafaxine and bupropion. In the first group, first 37.5 mg (one tablet) venlafaxine was administered daily, which was gradually increased up to 150 mg/day, depending on the patient´s response (alleviation of depressive symptoms) while the patient was visited for follow-up (every four weeks). In the second group, bupropion was initiated with 75 mg (one tablet) per day, and increased up to 300 mg/day based on the patient´s clinical response to the prescribed drug regimen. Both groups were under treatment for 12 weeks. The appearance of bupropion and venlafaxine drug in two groups were similar to each other (white round tablets). The patients did not know which of the two drugs they were receiving; however, the clinician was aware of the type of treatment. Also, to examine the laboratory findings (blood glucose control and lipid profile), the laboratory staff did not know the allocation. The patients were visited every 4 weeks for 3 months; in each visit, physical and laboratory examinations were performed again, and severity of depressive symptoms were assessed. In addition, the occurrence of drug side effects was surveyed.

Measures

At first, after obtaining informed consent, baseline information including demographic characteristics (age, gender, level of education, occupation, marital status, living condition, and place of residence), duration of diabetes, co-morbidities, and the used medications were recorded. Assessment of height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) was performed. The initial examination was performed by a medical student. The presence of depressive symptoms was assessed with the 21-item Beck depression inventory (BDI), and persons who had these symptoms were referred to the psychiatrist for clinical interview. Laboratory tests were carried out to measure fasting plasma glucose, two-hour postprandial blood sugar (2hpp BS), HbA1C level, and serum lipid profile (triglyceride, total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ). All these tests were carried out in a specified laboratory at baseline and 12 weeks after.

The primary outcomes were severity of depressive symptoms (based on the BDI score, fasting blood sugar, 2hpp BS, and HbA1C). The secondary outcomes were serum lipid profile (triglyceride, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol), and self-reported adverse reactions to the prescribed drugs. The research outcomes were evaluated every four weeks.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed in SPSS software, version 17. Chi-square, t-test, paired t-test, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were used for data analysis. Per-protocol analysis was performed to compare the research outcomes between two groups. P-value less than 0.05 was considered as the significant level.

Results

A total of 35 patients with T2D and depression completed the study. Baseline information for the two study groups are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

The study groups were not significantly different in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics (P>0.05). Mean age in venlafaxine and bupropion groups were 58.37±7.95 and 53.56±9.97 years, respectively (P=0.12). Comparison of the research outcomes between the two groups is presented in Table 3.

There was a significant decrease in depressive symptoms in both venlafaxine and bupropion groups; however, no statistically significant difference was found between them (P=0.342). The mean BMI in the venlafaxine group increased significantly (P=0.01), while the bupropion group showed a slightly decrease (P=0.10). These changes between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.003).

Fasting plasma glucose level in the venlafaxine group before and after the intervention was 167.36 and 184.05 mg/dL, respectively (P=0.14), while these values in the bupropion group were 160.75 and 159.50 mg/dL, respectively (P=0.87). It means that venlafaxine, unlike bupropion, increased fasting blood sugar, although these changes were not statistically significant. Furthermore, changes in fasting blood sugar between the two groups did not show a statistically significant difference, either (P=0.195).

The 2hpp BS before and after the intervention in the venlafaxine group was 252.00 and 250.73 mg/dL, respectively. In the group received bupropion, these values were 236.37 and 246.12 mg/dL, respectively. This shows that venlafaxine caused a slight decrease and bupropion caused an increase in 2hpp BS, these changes not statistically significant. The difference in 2hpp BS between the two groups was not statistically significant, either (P=0.756).

Venlafaxine caused a significant increase in HbA1c from 7.64 to 8.03 (P=0.04), and this value showed a decrease from 7.35 to 7.23 in the group received bupropion (P=0.06). The difference in HbA1c level was also significant between the two groups (P=0.028) (Figure 2). The results showed that venlafaxine administration changed the serum concentration of triglyceride (TG) from 218.63 to 241.00 mg/dL (P=0.07), while bupropion changed its level from 178.75 to 167.56 mg/dL (P=0.24). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.017). In the serum levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and total cholesterol, bupropion caused a slight decrease, while venlafaxine increased them; however, the difference between pretest and posttest levels and the difference between the two groups were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

The most common side effects reported for the two drugs, especially during the first weeks of treatment, were anxiety, nausea, and headache in the bupropion group, and nausea, insomnia, and loss of appetite in the venlafaxine group.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the therapeutic effects as well as adverse side-effects of bupropion and venlafaxine in patients with depression and T2D. The results showed the significant effect of both venlafaxine and bupropion on depressive symptoms. Although this effect was significant in both groups, no statistically significant decrease was observed between the two groups. Since the studies on comparing the effects of these two drugs are very limited [13], it was difficult to compare the findings of this research with their findings. A systematic review study on the effect of different antidepressants in patients with comorbid diabetes and depression demonstrated the positive effect of SSRIs, agomelatine, and bupropion on depressive symptoms in acute and maintenance phases and also on glycemic control [14]. Another review study suggested the SSRIs and bupropion as effective pharmacological interventions to improve depressive symptoms and prevent the recurrence of depression in patients with diabetes; furthermore, they showed the positive effect of SSRIs and bupropion on glycemic control of these individuals [15]. Gagnon et al. compared the effects of five antidepressants including citalopram, escitalopram, amitriptyline, venlafaxine, and trazodone on serum level of HbA1c in patients with diabetes, and reported better clinical outcomes for venlafaxine, amitriptyline, escitalopram and trazodone in comparison with citalopram [7].

In this study, glycemic profile showed heterogeneous changes following the drug interventions. Fasting plasma glucose level decreased in the bupropion group, but this change was not significant. In the venlafaxine group, fasting plasma glucose increased after the drug intervention, but the change was not significant, either. A significant change was observed in both groups in HbA1c; it decreased in the bupropion group, but increased in the venlafaxine group. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials for comparison of glycemic control following short-term (8-24 weeks) administration of different antidepressants in patients with T2D revealed the highest HbA1c reduction after taking vortioxetine, escitalopram and agomelatine [16]. In this review study, the clinical trials with administration of bupropion or venlafaxine were included in the review; therefore, we could not compare our findings with theirs. Several studies have reported SSRIs as effective drugs for glycemic control of patients with comorbid T2D and depression [16, 17]; however, there are limited clinical trials on the effect of bupropion and venlafaxine on the glycemic control.

In our study, the change in serum lipid profile was different between the two study groups. serum cholesterol, TG and LDL cholesterol decreased in the bupropion group, but increased in the venlafaxine group. Several studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of different antidepressants on lipid biomarkers [18]; however, the studies on diabetic patients comparing the antidepressant effects of bupropion and venlafaxine are limited. Some pathophysiological pathways involved in depression, such as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, change in circulating catecholamines and serum cortisol, and subsequently lipid disorder might be the reasons for the increase in lipid profile. Furthermore, antidepressants and dietary regimens can affect lipid biomarkers in these patients [13].

Another finding of this study was the effects of bupropion and venlafaxine on BMI; the venlafaxine group had a significant weight gain, but the bupropion group showed a slightly decrease in BMI. Uguz et al. also reported a significant weight gain following the administration of venlafaxine [19]. Gill et al. also showed the effect of bupropion on reducing weight [20]. Evidence suggests the role of serotonin and histamine off-target appetite-promoting pathways in adverse weight-gain effects of antidepressants [20].

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study that compares different clinical effects of venlafaxine and bupropion in patients with T2D and depression. However, there were some limitations and disadvantages such as non-completion of treatment course in some patients, not considering the presence of simultaneous stressors that can affect the patients´ mood such as financial and family problems, and not considering the dosage of medications used to control diabetes (oral medication or insulin) during the 12-week follow-up period. In addition, the study scale was a self-report tool, which can affect the research findings. Studies with large sample size and longer duration of follow-up, using structured interviews for evaluation of depressive symptoms are recommended.

Conclusion

Although venlafaxine can reduce depression, it is not suggested as a proper drug for treatment of depression in people with T2D due to its adverse effects on glycemic control, lipid profile and weight of the patients. However, bupropion can be considered as a treatment choice for patients with comorbid T2D and depression, due to favorable effects on depressive symptoms, weight reduction, glycemic control, and having low side effects,

Data availability statement

The data will be available for academic researchers with sending an email to the corresponding author (sussan.mouodi@gmail.com).

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All participants signed a written informed consent prior to the study. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Babol University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUBABOL.HRI.REC.1397.094). The study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20150630022991N12; available at https://en.irct.ir/trial/32944).

Funding

This study was financially supported by Babol University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and design: Mohammad Ali Bayani, Nikta Nekoofar, and Sussan Moudi; supervision: Mohammad Ali Bayani and Sussan Moudi; Data collection, data analysis, preparing initial draft, review, and approval of final draft: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Babol University of Medical Sciences for their financial support.

References

- Farooqi A, Gillies C, Sathanapally H, Abner S, Seidu S, Davies MJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the prevalence of depression between people with and without Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2022; 16(1):1-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.pcd.2021.11.001] [PMID]

- Amsah N, Md Isa Z, Ahmad N. Biopsychosocial and nutritional factors of depression among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4888. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19084888] [PMID]

- van der Feltz-Cornelis C, Allen SF, Holt RIG, Roberts R, Nouwen A, Sartorius N. Treatment for comorbid depressive disorder or subthreshold depression in diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2021; 11(2):e01981. [DOI:10.1002/brb3.1981] [PMID]

- Sridhar GR. Can the management of depression in type 2 diabetes be democratized? World J Diabetes. 2022; 13(3):203-12. [DOI:10.4239/wjd.v13.i3.203] [PMID]

- Petrak F, Röhrig B, Ismail K. Depression and diabetes. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2018. [PMID]

- Bayani MA, Shakiba N, Bijani A, Moudi S. Depression and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Caspian J Intern Med. 2022 Spring;13(2):335-342. [PMID]

- Gagnon J, Lussier MT, MacGibbon B, Daskalopoulou SS, Bartlett G. The impact of antidepressant therapy on glycemic control in canadian primary care patients with diabetes mellitus. Front Nutr. 2018; 5:47. [DOI:10.3389/fnut.2018.00047] [PMID]

- Markowitz SM, Gonzalez JS, Wilkinson JL, Safren SA. A review of treating depression in diabetes: Emerging findings. Psychosomatics. 2011; 52(1):1-18. [DOI:10.1016/j.psym.2010.11.007] [PMID]

- Sayuk GS, Gott BM, Nix BD, Lustman PJ. Improvement in sexual functioning in patients with type 2 diabetes and depression treated with bupropion. Diabetes Care. 2011; 34(2):332-4. [DOI:10.2337/dc10-1714] [PMID]

- Woo YS, Bahk WM, Seo JS, Park YM, Kim W, Jeong JH, et al. The Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder 2021: Comparisons with other treatment guidelines. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2022; 20(1):37-50. [DOI:10.9758/cpn.2022.20.1.37] [PMID]

- Coutens B, Yrondi A, Rampon C, Guiard BP. Psychopharmacological properties and therapeutic profile of the antidepressant venlafaxine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022; 239(9):2735-52. [DOI:10.1007/s00213-022-06203-8] [PMID]

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018; 391(10128):1357-66. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7] [PMID]

- Habib S, Sangaraju SL, Yepez D, Grandes XA, Talanki Manjunatha R. The nexus between diabetes and depression: A narrative review. Cureus. 2022; 14(6):e25611. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.25611]

- Roopan S, Larsen ER. Use of antidepressants in patients with depression and comorbid diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2017; 29(3):127-39. [DOI:10.1017/neu.2016.54] [PMID]

- Darwish L, Beroncal E, Sison MV, Swardfager W. Depression in people with type 2 diabetes: Current perspectives. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018; 11:333-43. [DOI:10.2147/DMSO.S106797] [PMID]

- Srisurapanont M, Suttajit S, Kosachunhanun N, Likhitsathian S, Suradom C, Maneeton B. Antidepressants for depressed patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of short-term randomized controlled trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022; 139:104731. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104731] [PMID]

- Diaz Bustamante L, Ghattas KN, Ilyas S, Al-Refai R, Maharjan R, Khan S. Does treatment for depression with collaborative care improve the glycemic levels in diabetic patients with depression? A systematic review. Cureus. 2020; 12(9):e10551. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.10551]

- Stuchtey FC, Block A, Osei F, Wippert PM. Lipid biomarkers in depression: Does antidepressant therapy have an impact? Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2022; 10(2):333. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare10020333] [PMID]

- Uguz F, Sahingoz M, Gungor B, Aksoy F, Askin R. Weight gain and associated factors in patients using newer antidepressant drugs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015; 37(1):46-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.10.011] [PMID]

- Gill H, Gill B, El-Halabi S, Chen-Li D, Lipsitz O, Rosenblat JD,et al. Antidepressant medications and weight change: A narrative review. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2020; 28(11):2064-72. [DOI:10.1002/oby.22969] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Endocrine diseases

Received: 2023/03/4 | Accepted: 2023/07/1 | Published: 2023/07/1

Received: 2023/03/4 | Accepted: 2023/07/1 | Published: 2023/07/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |