Thu, May 22, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 1, Issue 2 (Winter 2023)

CPR 2023, 1(2): 166-181 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kheirabadi G, Bagherian Sararoudi R, Talebi S, Khodadadi F. Investigating the Role of Illness Perception as a Mediator Between Personality Variables and Quality of Life (QoL) in Patients With Heart Attack, A Cross-sectional Study. CPR 2023; 1 (2) :166-181

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-35-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-35-en.html

Department of Health Psychology, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1681 kb]

(451 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (931 Views)

Full-Text: (359 Views)

Introduction

The clinical spectrum of coronary artery diseases varies from silent ischemia to chronic stable angina, unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death [1]. The increasing number of coronary artery diseases, its high mortality rate, and the dysfunction in affected people have made this disease to be the major cause of healthcare costs [2, 3]. Although with the invention of newer medical treatments as well as interventional and surgical techniques, the mortality rate caused by coronary heart diseases has gradually decreased over several decades, the approach of complementary interventions to improve the well-being and increase the quality of life (QoL) of patients has become more mandatory [4].

Having a good feeling in these patients plays an important role in their QoL; therefore, it is necessary to provide information regarding the correction of risk factors and deliver emotional support for patients during their recovery phase. Studies have shown that the personality model of these people is effective in creating well-being and satisfaction while increasing their QoL [5, 6]. Personality factors, in addition to affecting people’s feelings of well-being and QoL, may change their autonomic system and reduce the risk of coronary blood flow that leads to ischemia [7].

In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the concept of QoL as people’s understanding of their position in life in terms of culture, the value system in which they live, their goals, expectations, standards, and priorities. Newer definitions elaborate on the QoL as the difference between people’s expectations and reality. They have maintained that when the difference is smaller the difference, the QoL is higher [8]. Accordingly, the QoL is subjective and cannot be perceived by others and people’s perception is based on different aspects of their life [9]. Studies have shown that heart attack causes a significant decrease in health-related QoL [10].

Patients’ understanding of their disease is formed as disease perception or cognitive representation of the disease by the patient based on absorbing information from different sources and the patient’s beliefs. This factor can affect a person’s mental health and their ability to cope with the disease [11]. Studies have shown that patients who have negative perceptions and attitudes about their disease face greater disabilities in the future, reduce their recovery speed, and require more medical services, regardless of the actual severity of their disease [12]. In physical diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, the perception of the disease explains the difference in the consequences of the illness to a large extent [13]. Also, patients with the same condition and severity of symptoms have a different perception of their disease, which affects the behavior, performance, and severity of symptoms along with their consequences [14]. Analyzing 80 hospitalized patients with heart attacks, Helgeson showed the relationship between perceived control and depression, anxiety, and hostility [15]. Studies have shown that patients’ beliefs about the controllability of the disease in days after a heart attack are related to the occurrence of subsequent depression [16]. Patients who believe their heart attack will have serious consequences have a higher level of disability and a longer delay to return to work. Similarly, patients who have a negative attitude toward their heart disease or feel their disease is less curable participate less in rehabilitation programs [17]. The role of peoples’ perceptions in the QoL is very important. This issue is more pronounced in patients suffering from chronic diseases, such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases, etc. [8, 18].

In a study by Sluiter et al. in the Netherlands, the relationship between the perception of the disease, QoL, and the level of disability of 1121 patients with chronic diseases were evaluated. A group of patients who felt unwell and were unable to work had significantly more complaints and felt worse about their illness in addition to their living and working conditions. Both groups had the same concern about their illness but the number of complaints in the first group was 31% vs 49% for the second group [19].

The question raised about the relationship between QoL, disease perception, and personality patterns in patients with chronic diseases concerns the hierarchy of the impact of these variables on the QoL in these patients. This study is designed to investigate the possible role of illness perception as a mediator between personality variables and QoL in patients with a heart attack.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study to investigate the role of illness perception as a mediator between personality variables and QoL in patients with a heart attack. The study population included 193 heart attack patients in the Heart and Vascular Clinics of Chamran, Al-Zahra, and Khurshid hospitals in Isfahan City, Iran, from October to March 2018. The sampling method was a census considering all the people who met the criteria for entering the study during the sampling period.

Patients with a history of heart attack that was confirmed by a cardiologist were included in the study after completing the written consent to participate in the study, considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, patients who had a heart attack at least 6 to 12 months before the study, confirmed by a cardiologist, and were willing to participate in the study were included as well. Patients who had other chronic diseases, such as cancers or chronic diseases of other bodily systems were excluded from the study.

Data collection tools

The brief illness perception questionnaire

The brief-illness perception questionnaire was used to examine the perception of illness variable. This questionnaire has 9 subscales which were designed by Broadbent et al. based on the revised form of this questionnaire [20]. All subscales, except for the question related to the cause, are answered on a rating scale from 0 to 10. Each subscale measures one component of the perception of the disease. Five subscales measure the cognitive response to the disease, including the perception of the outcome (item 1), duration of the disease (item 2), personal control (item 3), control through treatment (item 4), and recognition of symptoms (item 5). Two subscales of worry about the disease (item 6) and emotions (item 8) measure the emotional response. One subscale measures the ability to understand the disease (item 7). The general orientation is an open question (item 9) in which the patient is asked to list 3 of the most important factors that based on their point of view have caused their illness. The reliability coefficient of this questionnaire has been reported by the test-retest method for each of the subscales from r=0.48 (ability to understand the disease) to r=0.70 (consequences) [20]. Bagharian et al. designed the Persian version of this scale. The Cronbach α of the Persian version is obtained at 0.84 and its correlation coefficient with the Persian version of the revised version of the illness perception questionnaire is 0.71 [21].

The 5-factor personality questionnaire

Costa and McGarry’s 5-factor personality questionnaire was used to determine personality traits. This questionnaire was first created by Costa and McGarry in 1985 [23]. At first, it included 181 statements to check 5 big personality factors, namely neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C). Then, the revised version included 240 items. Considering the length and complexity of this version, to use it more easily and quickly, a short version containing 60 questions and 12 items for each factor was made using the method of factor analysis [22, 23].

The 60-item version can be completed within 10 to 15 min. The items of this questionnaire are graded on a 5-point Likert scale from “completely disagree” to “completely agree,” and 5 points are obtained from the main dimensions of the personality spectrum. Costa and McGary obtained the Cronbach α coefficient for each of the neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C). subscales at 0.86, 0.80, 0.75, 0.69, and 0.79 respectively. The validity was reported as 0.83, 0.83, 0.91, 0.76, and 0.86, respectively for each subscale [23]. The Persian version of this questionnaire has been evaluated for 5 personality factors in a sample of the Iranian population, and the Cronbach α coefficient for each of the subscales of neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A) and conscientiousness (C) is obtained at 0.79, 0.73, 0.42, 0.58, and 0.77, respectively. The reliability index with the retest method is obtained at 0.84, 0.86, 0.78, 0.65, and 0.86, respectively for the subscales. The validity of the Persian version of this instrument for each of the subscales of neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C) were 0.75, 0.91, 0.78, 0.75, and 0.71, respectively [24].

The Short form 36 questionnaire

The short form 36 questionnaire was used to measure the QoL. This scale was created in 1993 by Ware et al. to examine the general health status. It includes 8 areas of physical performance, role limitations because of physical health problems, physical pains, and a person’s perception of general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations caused by emotional problems, and mental health. The reliability of this tool is reported in the range of 0.73 to 0.96. The time required to complete the questionnaire is around 5 to 10 min [25].

Montazeri et al. prepared the Persian version of this questionnaire, and in a study on a sample of 4163 subjects over 15 years old in Tehran City, Iran, the Cronbach α of this test was reported in the range of 0.77 to 0.90 (except for the vitality scale with the α of 0.65). The convergent validity of the questionnaire showed satisfactory results ranging from 0.58 to 0.95. In this study, the Iranian version of this questionnaire was reported to be valid and reliable in measuring health-related QoL in the general population [26].

The collected data were analyzed via the SPSS software, version 20 using the path analysis statistical method.

Results

In this study, 193 patients with a heart attack were examined, of which 128 people (66.32%) were men and 66 people (33.68%) were women. The mean age of the studied group was 61.4±10.7 years.

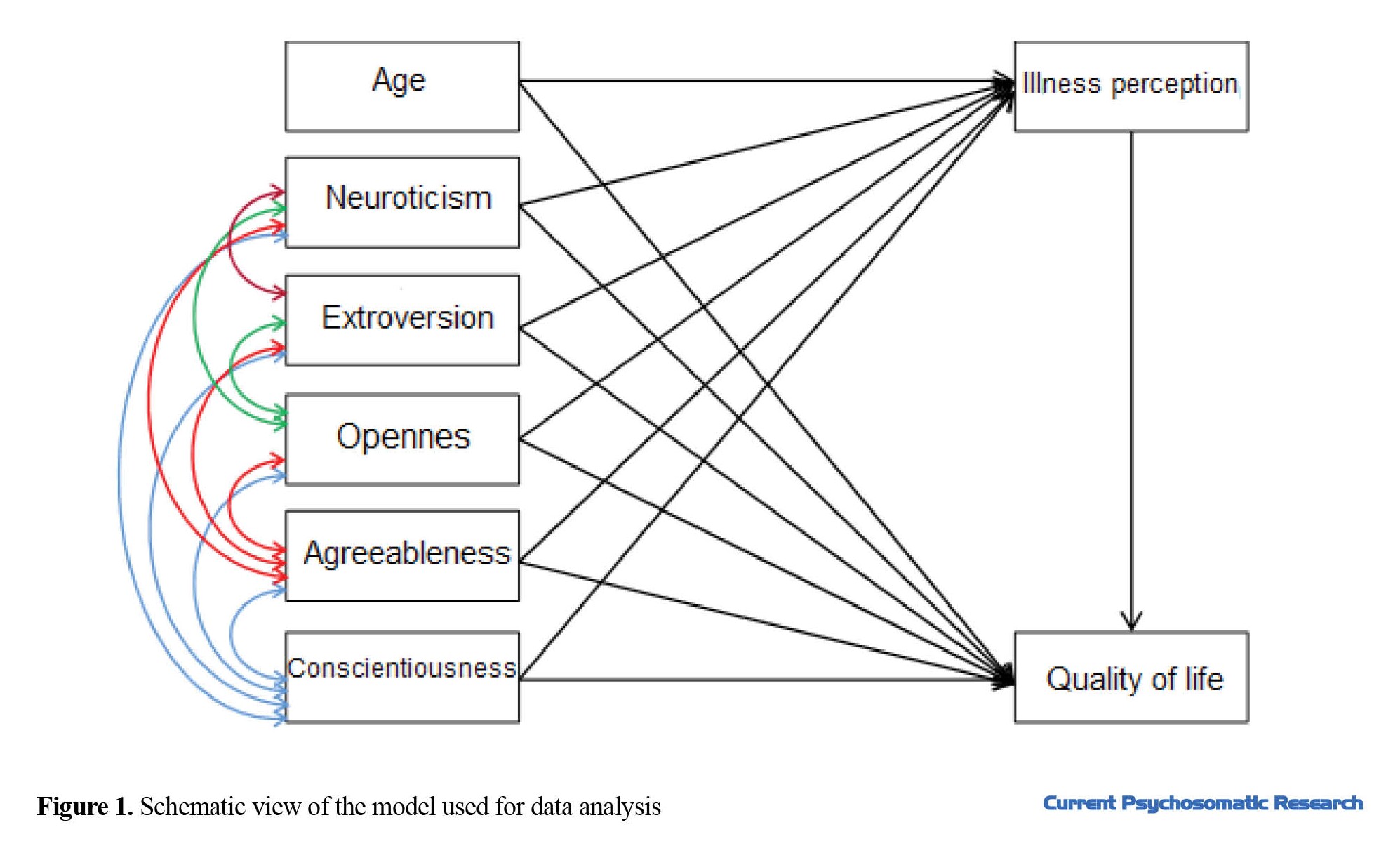

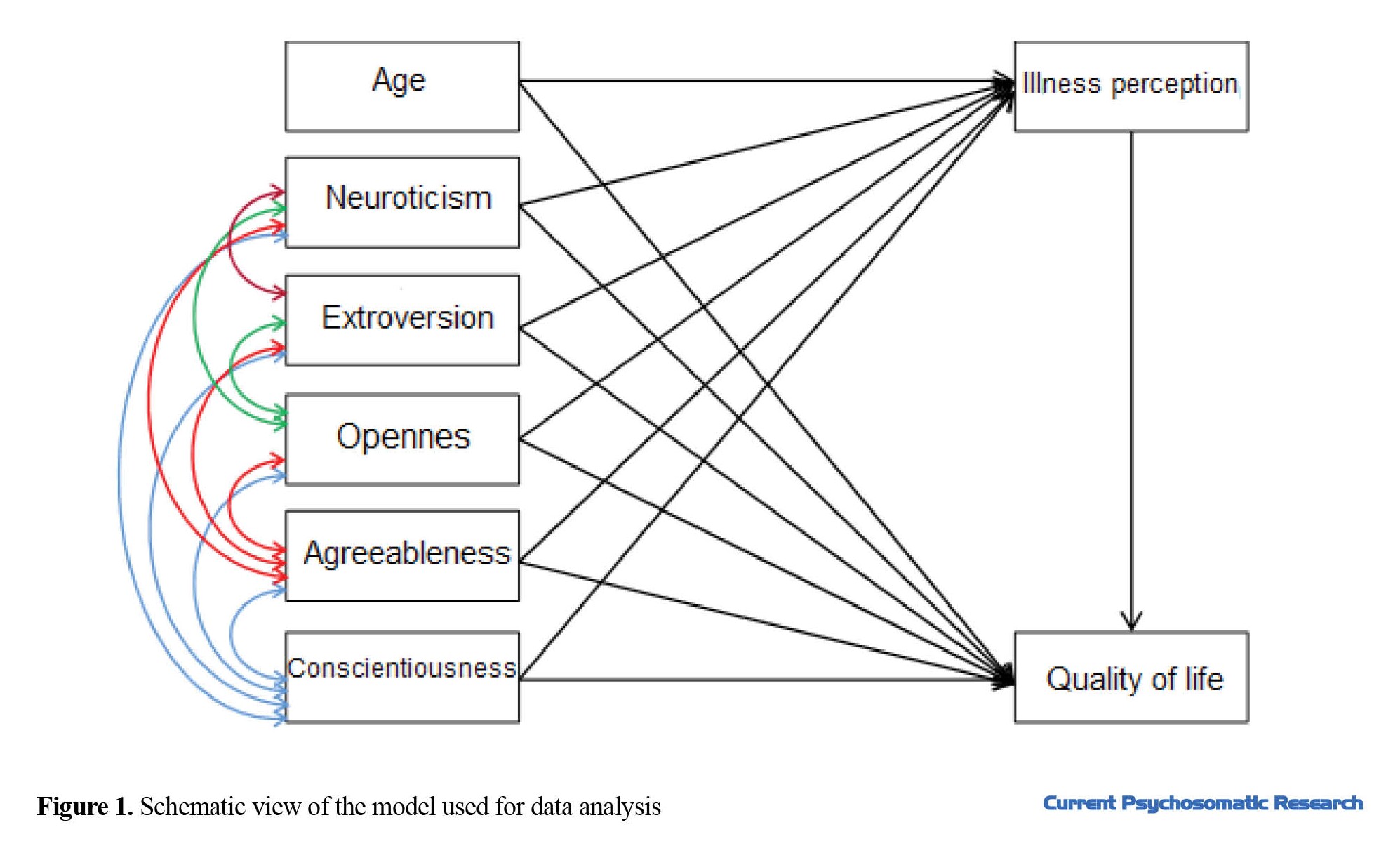

The path analysis model used in this study is suitable because the fit criteria of the model are as follows: incremental fit index (IFI)=0.984, comparative fit index (CFI)=0.982. Values closer to 1 show the better fitness of the model. Also, the root mean square error of approximation was equal to 0.066, and as the value is closer to 0, it shows the better fitness of the model (Figure 1).

In this study, the mean scores of neuroticism (N), extraversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C) were 31.9±7.9, 37.8±5.3, 36.9±5.3, 44.2±6.0, and 45.1±6.2, respectively.

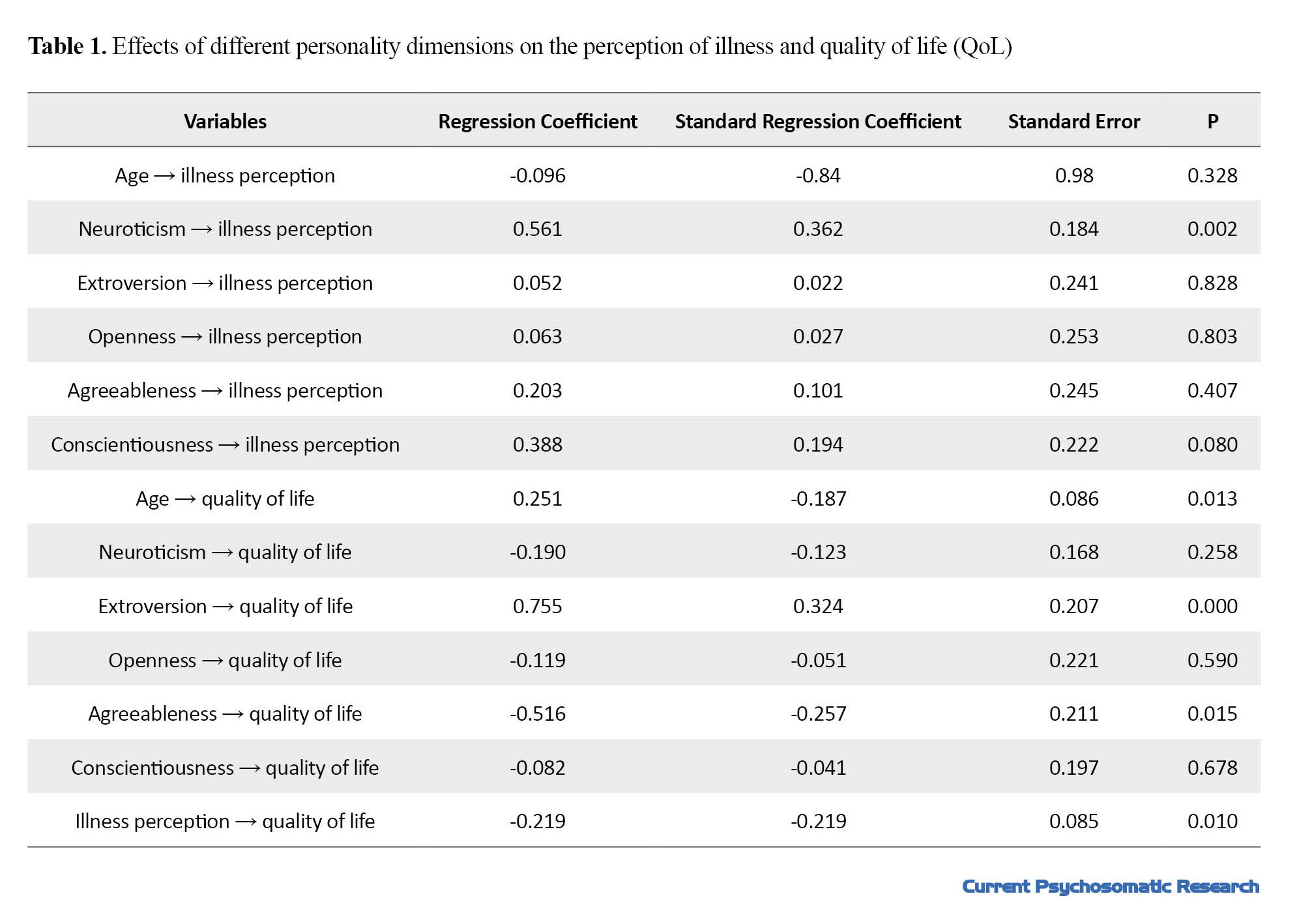

There was a significant direct relationship between the personality dimension of neuroticism and disease perception with a regression coefficient of 0.561 and P < 0.05. Other variables had no significant relationship with disease perception.

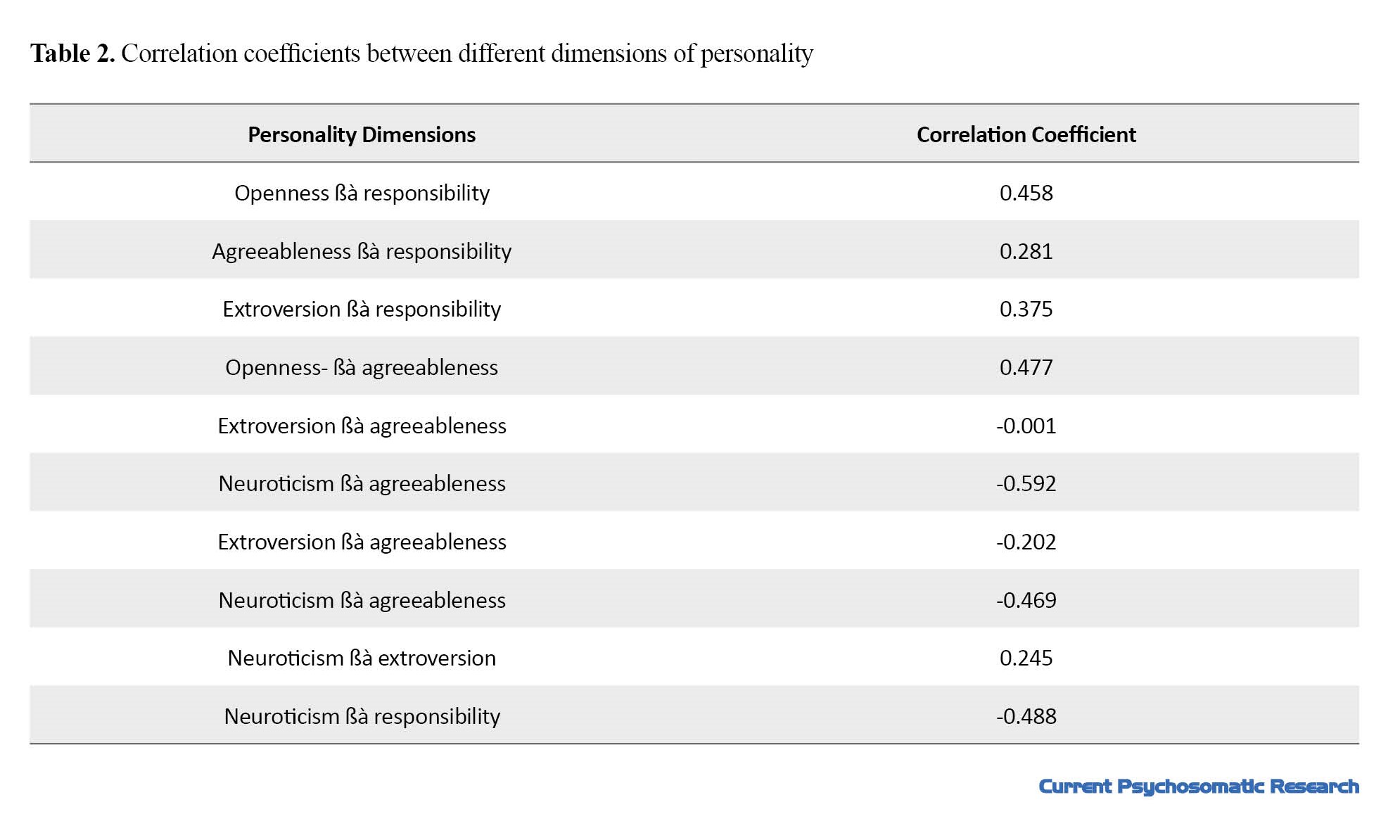

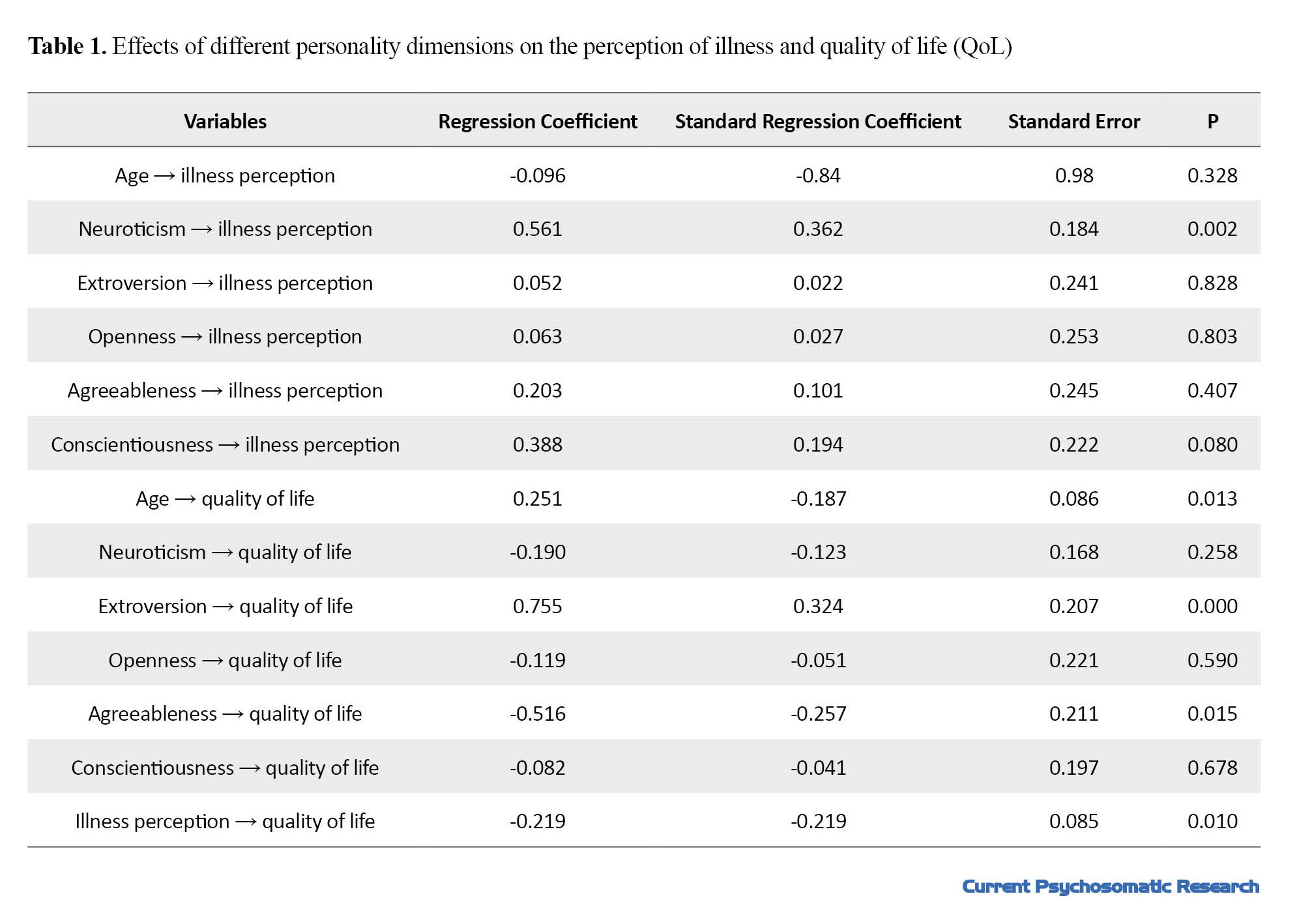

The effect of age and different personality dimensions of the patients on the perception of illness and QoL is shown in Table 1.

In this study, neuroticism had the greatest effect on disease perception, followed by conscientiousness, agreeableness, and age, and finally, extraversion which had respectively the least effect on disease perception. Regarding the QoL, extroversion had the greatest effect followed by variables of agreeableness, age, neuroticism, and openness had respectively the least effect on conscientiousness.

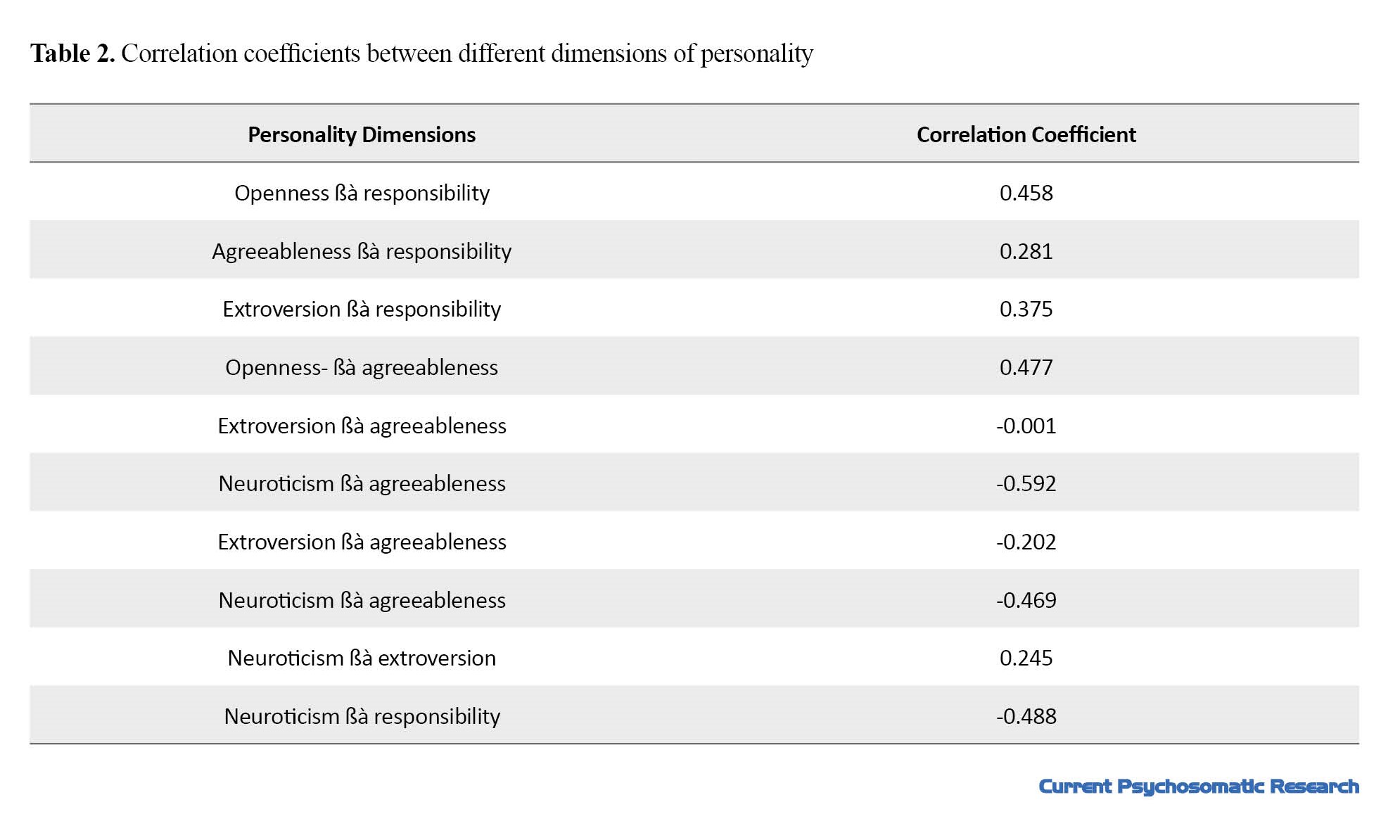

The relationship and correlation coefficients of each of the personality dimensions are also summarized in Table 2. As shown, the highest correlation was related to the two dimensions of neuroticism and agreeableness, demonstrating an inverse relationship.

Discussion

Evidence has confirmed the role of personality dimensions and disease perception on QoL. However, the mediating role of illness perception between personality factors and the patient’s QoL is unclear. This study aimed to investigate the role of illness perception as a mediator between personality variables and QoL in heart attack patients.

According to the findings, among the personality dimensions, only neuroticism had a significant positive relationship with the perception of the disease, and it caused a significant decrease in the QoL of people after a heart attack by affecting subjects’ perception of the disease.

People who are faced with a chronic illness form mental structures or cognitions of the disease in their cognitive system, affecting the formation of internal and external variables, such as personality factors, social environment, and demographic factors.

In this study, disease perception had a significant inverse relationship with QoL. Also, based on the findings in this study, personality dimensions of extroversion and agreeableness had a significant direct relationship with QoL. In this study, the social environment and cognitive factors, except for age, were not investigated. However, other variables, such as marital status, education level, and economic status have also been shown influential in past studies.

The literature shows that in a wide range of diseases (acute and chronic diseases), a person’s belief in the perception of the disease is effective in determining healthy behaviors and QoL [27, 28]. In a study conducted by Petrie et al., they showed that interventions designed to change the perception of illness in the hospital can lead to improved patient performance after myocardial infarction [29]. Some studies have shown that patients’ negative perception and attitude toward their disease is related to more disability in the future and a decrease in the speed of recovery [12]. Patients who believed that their heart attack will have serious consequences and had a negative attitude toward their heart disease had a higher disability level [17].

Additionally, studies have shown that people’s personality features are also effective in making people feel good and satisfied [3, 5, 6]. People with high extroversion characteristics follow active coping strategies and obtain social support, whereas people with high neuroticism characteristics participate in passive and inappropriate coping methods. Also, people with high-responsibility personalities avoid inappropriate coping strategies [30].

In this research, the neurotic personality dimension showed an inverse relationship with all personality dimensions, which can be consistent with the findings obtained in this study regarding the mediating effect of illness perception only between this dimension and QoL.

The lack of registering demographic data, such as education level, socio-economic status, and perceived social support status as well as the possible confounding role of these variables on the QoL are among the limitations of this study.

Conclusion

According to the findings of this research, anger, hostility, and worry in the form of personality dimensions of neuroticism with a direct effect on the perception of the disease cause a decrease in the QoL in heart attack patients, which can be formed by the incorrect perception of the disease in these people.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in the form of a general doctoral thesis. [Ethic Code:IR.MUI.MED.REC.1399.141]. The Informed written consent has been obtained from the participants in the research.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the M.D thesis of Sodeh Talebi, approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Gholamreza Kheirabadi and Reza Bagherian Sararoudi; Project administration, and funding acquisition: Sodeh Talebi; Supervision and visualization: Sodeh Talebi and Gholamreza Kheirabadi; Validation: Gholamreza Kheirabadi; Data Curation and original draft preparation: Farinaz Khodadadi and Sodeh Talebi; Data Analysis: Reza Bagherian Sararoudi; Software and resources: Farinaz Khodadadi; Writing Review & Editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article would like to thank all the patients who participated in this project and all the staff of the cardiology departments of Al-Zahra, Chamran and Khurshid hospitals in Isfahan city.

The clinical spectrum of coronary artery diseases varies from silent ischemia to chronic stable angina, unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death [1]. The increasing number of coronary artery diseases, its high mortality rate, and the dysfunction in affected people have made this disease to be the major cause of healthcare costs [2, 3]. Although with the invention of newer medical treatments as well as interventional and surgical techniques, the mortality rate caused by coronary heart diseases has gradually decreased over several decades, the approach of complementary interventions to improve the well-being and increase the quality of life (QoL) of patients has become more mandatory [4].

Having a good feeling in these patients plays an important role in their QoL; therefore, it is necessary to provide information regarding the correction of risk factors and deliver emotional support for patients during their recovery phase. Studies have shown that the personality model of these people is effective in creating well-being and satisfaction while increasing their QoL [5, 6]. Personality factors, in addition to affecting people’s feelings of well-being and QoL, may change their autonomic system and reduce the risk of coronary blood flow that leads to ischemia [7].

In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the concept of QoL as people’s understanding of their position in life in terms of culture, the value system in which they live, their goals, expectations, standards, and priorities. Newer definitions elaborate on the QoL as the difference between people’s expectations and reality. They have maintained that when the difference is smaller the difference, the QoL is higher [8]. Accordingly, the QoL is subjective and cannot be perceived by others and people’s perception is based on different aspects of their life [9]. Studies have shown that heart attack causes a significant decrease in health-related QoL [10].

Patients’ understanding of their disease is formed as disease perception or cognitive representation of the disease by the patient based on absorbing information from different sources and the patient’s beliefs. This factor can affect a person’s mental health and their ability to cope with the disease [11]. Studies have shown that patients who have negative perceptions and attitudes about their disease face greater disabilities in the future, reduce their recovery speed, and require more medical services, regardless of the actual severity of their disease [12]. In physical diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, the perception of the disease explains the difference in the consequences of the illness to a large extent [13]. Also, patients with the same condition and severity of symptoms have a different perception of their disease, which affects the behavior, performance, and severity of symptoms along with their consequences [14]. Analyzing 80 hospitalized patients with heart attacks, Helgeson showed the relationship between perceived control and depression, anxiety, and hostility [15]. Studies have shown that patients’ beliefs about the controllability of the disease in days after a heart attack are related to the occurrence of subsequent depression [16]. Patients who believe their heart attack will have serious consequences have a higher level of disability and a longer delay to return to work. Similarly, patients who have a negative attitude toward their heart disease or feel their disease is less curable participate less in rehabilitation programs [17]. The role of peoples’ perceptions in the QoL is very important. This issue is more pronounced in patients suffering from chronic diseases, such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases, etc. [8, 18].

In a study by Sluiter et al. in the Netherlands, the relationship between the perception of the disease, QoL, and the level of disability of 1121 patients with chronic diseases were evaluated. A group of patients who felt unwell and were unable to work had significantly more complaints and felt worse about their illness in addition to their living and working conditions. Both groups had the same concern about their illness but the number of complaints in the first group was 31% vs 49% for the second group [19].

The question raised about the relationship between QoL, disease perception, and personality patterns in patients with chronic diseases concerns the hierarchy of the impact of these variables on the QoL in these patients. This study is designed to investigate the possible role of illness perception as a mediator between personality variables and QoL in patients with a heart attack.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study to investigate the role of illness perception as a mediator between personality variables and QoL in patients with a heart attack. The study population included 193 heart attack patients in the Heart and Vascular Clinics of Chamran, Al-Zahra, and Khurshid hospitals in Isfahan City, Iran, from October to March 2018. The sampling method was a census considering all the people who met the criteria for entering the study during the sampling period.

Patients with a history of heart attack that was confirmed by a cardiologist were included in the study after completing the written consent to participate in the study, considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, patients who had a heart attack at least 6 to 12 months before the study, confirmed by a cardiologist, and were willing to participate in the study were included as well. Patients who had other chronic diseases, such as cancers or chronic diseases of other bodily systems were excluded from the study.

Data collection tools

The brief illness perception questionnaire

The brief-illness perception questionnaire was used to examine the perception of illness variable. This questionnaire has 9 subscales which were designed by Broadbent et al. based on the revised form of this questionnaire [20]. All subscales, except for the question related to the cause, are answered on a rating scale from 0 to 10. Each subscale measures one component of the perception of the disease. Five subscales measure the cognitive response to the disease, including the perception of the outcome (item 1), duration of the disease (item 2), personal control (item 3), control through treatment (item 4), and recognition of symptoms (item 5). Two subscales of worry about the disease (item 6) and emotions (item 8) measure the emotional response. One subscale measures the ability to understand the disease (item 7). The general orientation is an open question (item 9) in which the patient is asked to list 3 of the most important factors that based on their point of view have caused their illness. The reliability coefficient of this questionnaire has been reported by the test-retest method for each of the subscales from r=0.48 (ability to understand the disease) to r=0.70 (consequences) [20]. Bagharian et al. designed the Persian version of this scale. The Cronbach α of the Persian version is obtained at 0.84 and its correlation coefficient with the Persian version of the revised version of the illness perception questionnaire is 0.71 [21].

The 5-factor personality questionnaire

Costa and McGarry’s 5-factor personality questionnaire was used to determine personality traits. This questionnaire was first created by Costa and McGarry in 1985 [23]. At first, it included 181 statements to check 5 big personality factors, namely neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C). Then, the revised version included 240 items. Considering the length and complexity of this version, to use it more easily and quickly, a short version containing 60 questions and 12 items for each factor was made using the method of factor analysis [22, 23].

The 60-item version can be completed within 10 to 15 min. The items of this questionnaire are graded on a 5-point Likert scale from “completely disagree” to “completely agree,” and 5 points are obtained from the main dimensions of the personality spectrum. Costa and McGary obtained the Cronbach α coefficient for each of the neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C). subscales at 0.86, 0.80, 0.75, 0.69, and 0.79 respectively. The validity was reported as 0.83, 0.83, 0.91, 0.76, and 0.86, respectively for each subscale [23]. The Persian version of this questionnaire has been evaluated for 5 personality factors in a sample of the Iranian population, and the Cronbach α coefficient for each of the subscales of neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A) and conscientiousness (C) is obtained at 0.79, 0.73, 0.42, 0.58, and 0.77, respectively. The reliability index with the retest method is obtained at 0.84, 0.86, 0.78, 0.65, and 0.86, respectively for the subscales. The validity of the Persian version of this instrument for each of the subscales of neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C) were 0.75, 0.91, 0.78, 0.75, and 0.71, respectively [24].

The Short form 36 questionnaire

The short form 36 questionnaire was used to measure the QoL. This scale was created in 1993 by Ware et al. to examine the general health status. It includes 8 areas of physical performance, role limitations because of physical health problems, physical pains, and a person’s perception of general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations caused by emotional problems, and mental health. The reliability of this tool is reported in the range of 0.73 to 0.96. The time required to complete the questionnaire is around 5 to 10 min [25].

Montazeri et al. prepared the Persian version of this questionnaire, and in a study on a sample of 4163 subjects over 15 years old in Tehran City, Iran, the Cronbach α of this test was reported in the range of 0.77 to 0.90 (except for the vitality scale with the α of 0.65). The convergent validity of the questionnaire showed satisfactory results ranging from 0.58 to 0.95. In this study, the Iranian version of this questionnaire was reported to be valid and reliable in measuring health-related QoL in the general population [26].

The collected data were analyzed via the SPSS software, version 20 using the path analysis statistical method.

Results

In this study, 193 patients with a heart attack were examined, of which 128 people (66.32%) were men and 66 people (33.68%) were women. The mean age of the studied group was 61.4±10.7 years.

The path analysis model used in this study is suitable because the fit criteria of the model are as follows: incremental fit index (IFI)=0.984, comparative fit index (CFI)=0.982. Values closer to 1 show the better fitness of the model. Also, the root mean square error of approximation was equal to 0.066, and as the value is closer to 0, it shows the better fitness of the model (Figure 1).

In this study, the mean scores of neuroticism (N), extraversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C) were 31.9±7.9, 37.8±5.3, 36.9±5.3, 44.2±6.0, and 45.1±6.2, respectively.

There was a significant direct relationship between the personality dimension of neuroticism and disease perception with a regression coefficient of 0.561 and P < 0.05. Other variables had no significant relationship with disease perception.

The effect of age and different personality dimensions of the patients on the perception of illness and QoL is shown in Table 1.

In this study, neuroticism had the greatest effect on disease perception, followed by conscientiousness, agreeableness, and age, and finally, extraversion which had respectively the least effect on disease perception. Regarding the QoL, extroversion had the greatest effect followed by variables of agreeableness, age, neuroticism, and openness had respectively the least effect on conscientiousness.

The relationship and correlation coefficients of each of the personality dimensions are also summarized in Table 2. As shown, the highest correlation was related to the two dimensions of neuroticism and agreeableness, demonstrating an inverse relationship.

Discussion

Evidence has confirmed the role of personality dimensions and disease perception on QoL. However, the mediating role of illness perception between personality factors and the patient’s QoL is unclear. This study aimed to investigate the role of illness perception as a mediator between personality variables and QoL in heart attack patients.

According to the findings, among the personality dimensions, only neuroticism had a significant positive relationship with the perception of the disease, and it caused a significant decrease in the QoL of people after a heart attack by affecting subjects’ perception of the disease.

People who are faced with a chronic illness form mental structures or cognitions of the disease in their cognitive system, affecting the formation of internal and external variables, such as personality factors, social environment, and demographic factors.

In this study, disease perception had a significant inverse relationship with QoL. Also, based on the findings in this study, personality dimensions of extroversion and agreeableness had a significant direct relationship with QoL. In this study, the social environment and cognitive factors, except for age, were not investigated. However, other variables, such as marital status, education level, and economic status have also been shown influential in past studies.

The literature shows that in a wide range of diseases (acute and chronic diseases), a person’s belief in the perception of the disease is effective in determining healthy behaviors and QoL [27, 28]. In a study conducted by Petrie et al., they showed that interventions designed to change the perception of illness in the hospital can lead to improved patient performance after myocardial infarction [29]. Some studies have shown that patients’ negative perception and attitude toward their disease is related to more disability in the future and a decrease in the speed of recovery [12]. Patients who believed that their heart attack will have serious consequences and had a negative attitude toward their heart disease had a higher disability level [17].

Additionally, studies have shown that people’s personality features are also effective in making people feel good and satisfied [3, 5, 6]. People with high extroversion characteristics follow active coping strategies and obtain social support, whereas people with high neuroticism characteristics participate in passive and inappropriate coping methods. Also, people with high-responsibility personalities avoid inappropriate coping strategies [30].

In this research, the neurotic personality dimension showed an inverse relationship with all personality dimensions, which can be consistent with the findings obtained in this study regarding the mediating effect of illness perception only between this dimension and QoL.

The lack of registering demographic data, such as education level, socio-economic status, and perceived social support status as well as the possible confounding role of these variables on the QoL are among the limitations of this study.

Conclusion

According to the findings of this research, anger, hostility, and worry in the form of personality dimensions of neuroticism with a direct effect on the perception of the disease cause a decrease in the QoL in heart attack patients, which can be formed by the incorrect perception of the disease in these people.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in the form of a general doctoral thesis. [Ethic Code:IR.MUI.MED.REC.1399.141]. The Informed written consent has been obtained from the participants in the research.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the M.D thesis of Sodeh Talebi, approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Gholamreza Kheirabadi and Reza Bagherian Sararoudi; Project administration, and funding acquisition: Sodeh Talebi; Supervision and visualization: Sodeh Talebi and Gholamreza Kheirabadi; Validation: Gholamreza Kheirabadi; Data Curation and original draft preparation: Farinaz Khodadadi and Sodeh Talebi; Data Analysis: Reza Bagherian Sararoudi; Software and resources: Farinaz Khodadadi; Writing Review & Editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article would like to thank all the patients who participated in this project and all the staff of the cardiology departments of Al-Zahra, Chamran and Khurshid hospitals in Isfahan city.

References

- George J. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. In: Abbas AE, editor. Interventional cardiology imaging: An essential guide. London: Springer; 2015. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4471-5239-2_3]

- Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Sanborn TA, White HD, Talley JD, et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK investigators. Should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341(9):625-34. [DOI:10.1056/NEJM199908263410901] [PMID]

- Meijer A, Conradi HJ, Bos EH, Thombs BD, van Melle JP, de Jonge P. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis of 25 years of research. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011; 33(3):203-16 [DOI:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.02.007] [PMID]

- Chacko L, Howard JP, Rajkumar C, Nowbar AN, Kane C, Mahdi D, et al. Effects of percutaneous coronary intervention on death and myocardial infarction stratified by stable and unstable coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020; 13(2):e006363. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006363] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Serrano CV Jr, Setani KT, Sakamoto E, Andrei AM, Fraguas R. Association between depression and development of coronary artery disease: Pathophysiologic and diagnostic implications. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011; 7:159-64. [DOI:10.2147/VHRM.S10783] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kubzansky LD, Park N, Peterson C, Vokonas P, Sparrow D. Healthy psychological functioning and incident coronary heart disease: The importance of self-regulation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(4):400-8. [DOI:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.23] [PMID]

- Dasa O, Mahmoud AN, Kaufmann PG, Ketterer M, Light KC, Raczynski J, et al. Relationship of psychological characteristics to daily life ischemia: An analysis from the national heart, lung, and blood institute psychophysiological investigations in myocardial ischemia. Psychosom Med. 2022; 84(3):359-67. [DOI:10.1097/PSY.0000000000001044] [PMID]

- Canam C, Acorn S. Quality of life for family caregivers of people with chronic health problems. Rehabil Nurs. 1999; 24(5):192-6. [DOI:10.1002/j.2048-7940.1999.tb02176.x] [PMID]

- Porumb Andrese E, Vâță D, Postolică R, Stătescu L, Stătescu C, Grăjdeanu AI, et al. Association between personality type, affective distress profile and quality of life in patients with psoriasis vs. patients with cardiovascular disease. Exp Ther Med. 2019; 18(6):4967-73. [DOI:10.3892/etm.2019.7933] [PMCID]

- Schweikert B, Hunger M, Meisinger C, Konig HH, Gapp O, Holle R. Quality of life several years after myocardial infarction: Comparing the MONICA/KORA registry to the general population. Eur Heart J. 2009; 30(4):436-43. [DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn509] [PMID]

- Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steele DJ. Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Taylor SE, Singer JE, Baum A, editors. Handbook of psychology and health. London: Routledge; 2020. [DOI:10.4324/9781003044307-9]

- Fanakidou I, Zyga S, Alikari V, Tsironi M, Stathoulis J, Theofilou P. Mental health, loneliness, and illness perception outcomes in quality of life among young breast cancer patients after mastectomy: The role of breast reconstruction. Qual Life Res. 2018; 27(2):539-43. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-017-1735-x] [PMID]

- Khandaker GM, Zuber V, Rees J, Carvalho L, Mason AM, Foley CN, et al. Shared mechanisms between coronary heart disease and depression: Findings from a large UK general population-based cohort. Mol Psychiatry. 2020; 25(7):1477-86. [DOI:10.1038/s41380-019-0395-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sawyer AT, Harris SL, Koenig HG. Illness perception and high readmission health outcomes. Health Psychol Open. 2019; 6(1):2055102919844504. [DOI:10.1177/2055102919844504] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Thompson SC, Kyle DJ. The role of perceived control in coping with the losses associated with chronic illness. In: Harvey J, Miller E, editors. Loss and trauma. New York: Routledge; 2000. [DOI:10.4324/9781315783345-11]

- Bagherian R, Bahrami H, Guilani B, Saneei H. [Personal perceived control and post- MI depression (Persian)]. J Clin Psycho. 2009; 1(2):61-70. [DOI:10.22075/jcp.2017.1974]

- Stendardo M, Bonci M, Casillo V, Miglio R, Giovannini G, Nardini M, et al. Predicting return to work after acute myocardial infarction: Socio-occupational factors overcome clinical conditions. PloS One. 2018; 13(12):e0208842. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0208842] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Edwards B, Ung L. Quality of life instruments for caregives of patients with cancer: A review of their psychometric properties. Cancer Nurs. 2002; 25(5):342-9. [DOI:10.1097/00002820-200210000-00002] [PMID]

- van der Ende-van Loon MC, Nieuwkerk PT, van Stiphout SH, Scheffer RC, de Ridder RJ, Pouw RE, et al. Barrett esophagus: Quality of life and factors associated with illness perception. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022; 10(7):721-9. [DOI:10.1002/ueg2.12266] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006; 60(6):631-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020] [PMID]

- Bagherian R, BahramiEhsan H, Sanei H. [Relationship between history of myocardial infarction and cognitive representation of myocardial infarction (Persian)]. J Res Psychol Health. 2008; 2(2):29-39. [Link]

- Barrick MR, Mount MK. The big fivepersonality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psych. 1991; 44(1):1-26. [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x]

- Garousi MT, Mehryar AH, Ghazi Tabatabaei M. [Application of the NEO PIR test and analytic evaluation of its characteristics and factorial structure among Iranian university students (Persian)]. J Humanit. 2001; 11(39):173-98. [Link]

- Attari Y, Aman A, Elahifard A, Mehrabizadeh A, Honarmand M. [An inevetigation of relationship between personality characteristics and family-personal factors and marital satisfaction in administrative office personnel in Ahvaz (Persian)]. J Educ Psychol. 2006; 13(3):81-108. [Link]

- Anderson C, Laubscher S, Burns R. Validation of the short form 36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire among stroke patients. Stroke. 1996; 27(10):1812-6. [DOI:10.1161/01.STR.27.10.1812] [PMID]

- Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005; 14(3):875-82 [DOI:10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5] [PMID]

- Van Ittersum MW, Van Wilgen CP, Hilberdink WK, Groothoff JW, Van Der Schans CP. Illness perceptions in patients with fibromyalgia. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 74(1):53-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.041] [PMID]

- Clarke D, Goosen T. The mediating effects of coping strategies in the relationship between automatic negative thoughts and depression in a clinical sample of diabetes patients. Pers Individ Dif. 2009; 46(4):460-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2008.11.014]

- Petrie KJ, Cameron LD, Ellis CJ, Buick D, Weinman J. Changin illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: An early intervention randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2002; 64(4):580-6 [DOI:10.1097/00006842-200207000-00007] [PMID]

- Watson D, Hubbard B. Adaptational style and dispositional structure: Coping in the context of the Five-Factor model. J Personal. 1996; 64(4):737-74. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00943.x]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2022/09/20 | Accepted: 2023/04/3 | Published: 2023/01/1

Received: 2022/09/20 | Accepted: 2023/04/3 | Published: 2023/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |