Wed, Dec 24, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 1, Issue 1 (Autumn 2022)

CPR 2022, 1(1): 28-49 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Farhadi N, Ezati M, Shojaie A A, Hatami J, Salehi K. Cognitive Errors Associated With Medical Decision-Making: A Systematic Review. CPR 2022; 1 (1) :28-49

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-31-en.html

URL: http://cpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-31-en.html

Department of Education Management and Planing, Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Medical decision-making, Physician, Qualitative research, Clinical decision-making, Cognitive errors

Full-Text [PDF 4999 kb]

(1398 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3001 Views)

Full-Text: (1135 Views)

Introduction

Medical decision-making is full of uncertainty. A substantial percentage of decision-making biases were credited to physicians’ cognitive functions [1]. Human errors in medicine can be reduced through advances in cognitive sciences [2]. As a result, extensive research has been carried out on the discipline of cognitive psychology to decrease clinicians’ decision-making errors. These are among the most significant patient safety issues and the subject of much worldwide research work [3, 4]. Diagnostic errors lead to fatalities in nearly one in every 1000 cases, resulting in an estimated 40000 to 120000 deaths per year in the USA [5, 6]. Estimates indicate that financial decrement caused by unnecessary testing, treatment, and fatalities due to diagnostic mistakes accounts for almost 30% of yearly national healthcare costs in the USA [7]. Investigations on medical errors and their causes have significantly improved over the last two decades with cognitive psychology [8]. The core component of the diagnosis is decision-making, and medical decision-making is susceptible to biases. The Sullivan Group [9] reported personal encounters with numerous instances of highly veteran doctors and experienced clinicians committing deep biases affecting the thinking process [10]. David Eddy commented that clinical decision-making was not a viable field of research in the 1970s [11]. However, some claim that the modifications are not very significant since then. In a study of directors of medical clerkships, more than half said they did not give courses in clinical decision-making and thought less than 5% of students had excellent decision-making skills [12]. In the last decade, the interest in understanding medical decisions in dynamic areas has significantly increased. Biases caused by defective thinking processes, rather than insufficient knowledge, are referred to as cognitive biases, and they can be brought on by heuristics, emotions, prejudices, and other cognitive foundations which are not reasonable [13, 25]. Therefore, students should be educated about various biases in clinical decision-making and various strategies used for cognitive bias mitigation [14].

In previous research, all cognitive errors have not been coherently addressed, and few studies have examined cognitive errors in physicians’ decisions. This article is an up-to-date, systematic meta-analyses review concentrated on the highly-repeated, significant errors in the reviewed articles 40 cognitive errors based on the repetition count disregarding their incidence and general prevalence rate.

This review study aimed at identifying the cognitive errors associated with physicians’ decisions with the following main research question: According to available qualitative research, what cognitive factors are associated with physicians’ decisions?

Materials and Method

The recommended reporting items for systematic review (PRISMA or Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) standards were followed in this qualitative systematic review study report [15], as well as the enhancement of reporting transparency for the synthesis of qualitative research findings [16, 17].

Data sources

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tehran, Faculty of Psychology and Education (Medical Ethic No: IR. UT. PSYEDU. REC.1401/ 032/). This review considered qualitative research studies containing the information, including each study’s data collection and analysis, both of which used qualitative approaches. PubMed and Medline were systematically searched for relevant posts on cognitive mistakes. Due to imposed sanctions on Iran, Embase articles were not accessible.

Study selection

Articles that met one or more of the following four inclusion criteria were considered candidates for the study: at least one outcomes measure was reported, the study was published in English, it involved doctors, and at least one cognitive element or an error was examined and predefined. The articles that met the requirements for inclusion were examined for any cognitive errors, methodological issues, and the expansion of the impact on therapeutic or diagnostic judgment. Non-qualitative studies and those with a statistical population of non-physicians were excluded. The study used the data that the authors had reported.

Search strategy

In studies published in English from 2000 to 2022, in the last two decades, the cognitive errors that physicians made in diagnosing and decision-making were investigated. The search included the following MeSH terms: “Cognitive bias” [or] “decision-making”, [or] “clinical decision-making”, [or] “medical decision-making”, [or] “physician” and “qualitative research” and a combination of them.

Selection process

Two authors independently screened the titles and read the title-relevant abstracts. Two researchers retrieved and reviewed the full papers for related abstracts, and they also checked the entire texts of possibly qualified publications for the inclusion criteria. Disagreements are resolved through discussion and consensus. Data extracted literatim from selected papers directly into the NVivo-11 program. Before including in the evaluation, the methodological quality of the papers was assessed by two independent reviewers utilizing the PRISMA instrumentation. Cohen’s kappa also applied to assess agreement, and the kappa score of at least 0.72 indicated good agreement among observers.

Data extraction

The study data were extracted according to the PRISMA statement (Figure 1). To ensure the necessary accuracy and correct extraction of content from the articles, two reviewers looked at the titles and abstracts. Utilizing standardized collecting appearances, data were extracted. Data were gathered based on the study country, design, publication year, the number of studied cognitive errors, type of results, and summary of essential findings.

Data analysis

The findings from qualitative investigations were first classified line by line while taking both content and meaning into consideration. Rereading and recoding were required during this procedure, as well as discussions among the research team to ascertain whether new codes were required or the current codes should be reevaluated. Through a deductive method, the analysis was theoretically motivated by the literature on cognitive reasoning models. The researchers also kept an eye out for any fresh ideas that might come from the data alone. As a result, the development of descriptive themes was based on the correspondence of concepts from one study to another, which allowed for the recognition of similar concepts between studies and the creation of a hierarchical coding structure based on similarities and differences between codes. According to Thomas and Harden, the third stage comprised an iterative study of the outcomes of the previous two stages [18].

Data items

As shown in Table 1, the following additional data were gathered for each included study: title, authors, publication year, country of origin, method, and journal title.

.jpg)

Results

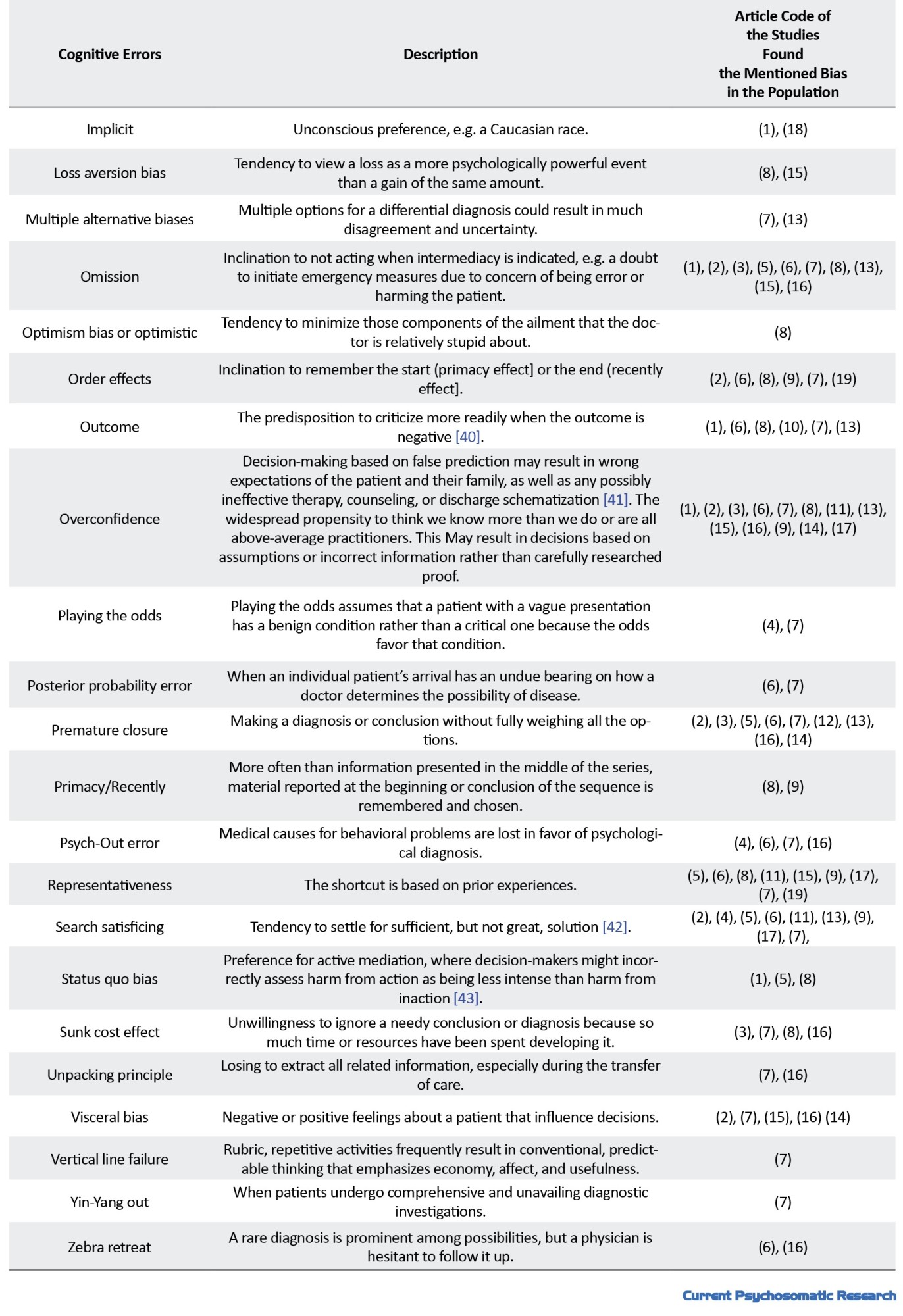

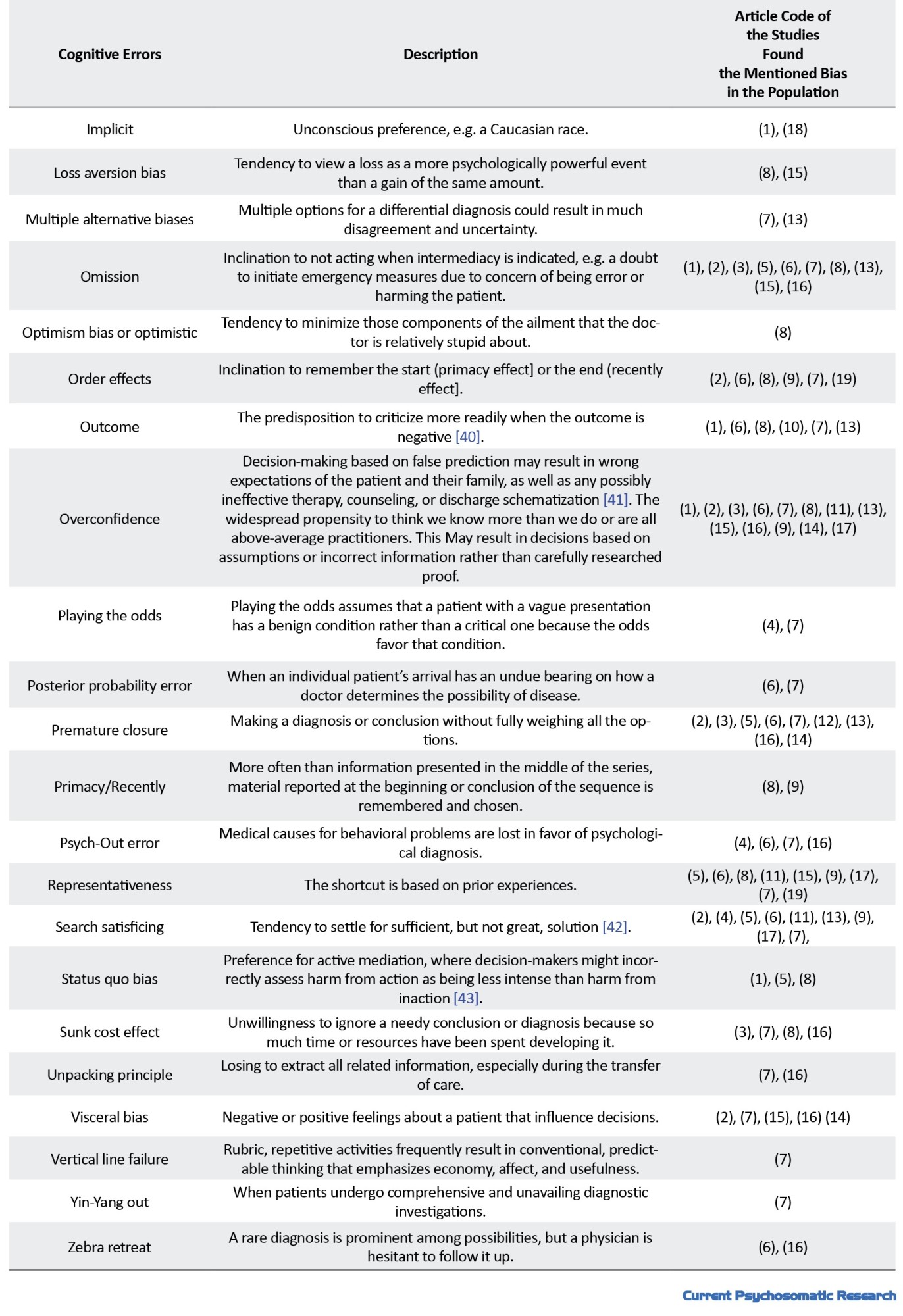

Table 2 lists cognitive errors reported in 19 reviewed studies.

From the 19 analyzed studies, 40 cognitive errors were found: Aggregate, ambiguity aversion, yin-yang out, feedback sanction, visceral, anchoring, vertical line failure, ascertainment, unpacking principle, availability, sunk costs, base rate neglect, bias blind spot, conjunction rule, commission, confirmation, diagnosis momentum, explicit, framing effect, search satisfying, fundamental attribution, representativeness restraint, gambler’s fallacy, psych-out, gender error, hindsight, implicit, loss aversion, multiple alternatives, omission, optimism or optimistic, order effects, posterior probability, outcome, premature closure, overconfidence, zebra retreat, playing the odds, posterior probability, primacy or recently, and status quo. Table 3 presents a description of these cognitive errors.

Forty cognitive errors based on repetition count in the reviewed articles are shown in Figure 2. Discussion

Cognitive errors contribute significantly to medical mishaps. The evidence offered in this review suggests that attendance of error leads to errors in decision-making, and the outcomes of decisions are very concerning. Hence, the patient might be assessed, diagnosed, or given different treatments or services due to the presence or absence of information that should not have been included in the decision-making process. Therefore, cognitive, affective, or other errors can negatively affect the overall quality of medical decision-making. As shown in Figure 3, from 40 cognitive errors obtained from the 19 reviewed studies, 11 cognitive errors accounted for the largest repetition counts: availability (16 times), confirmation (15 times), overconfidence (13 times), anchoring (12 times), framing effect (10 times), omission (10 times), search satisficing (9 times), representativeness (9 times), premature closure (9 times), diagnosis momentum (9 times), and commission (9 times). The frequency of diagnostic bias is disappointingly numerous. Early detection of medical professionals’ cognitive errors is essential to improve clinical judgment and avoid clinical biases and imply more realistic patient expectations. This study determines the impact of doctors’ cognitive biases on clinical biases and medical tasks. Studies examining the anchoring effect, physician overconfidence, and information or availability inaccuracy may point to a connection with inaccurate diagnoses. Physicians’ enhanced coping strategies and ambiguity tolerance can be related to optimal management. Even while decision-making processes are similar across professions, mistakes would nonetheless play a substantial impact on decision outcomes in all healthcare contexts. The numbers reported for errors in this article, although relatively demonstrating the prevalence of cognitive errors occurring in physicians’ decisions, indicate such errors’ repetitions in the 19 reviewed articles, i.e., opinions of the authors were prioritized, as well as a deeper feeling, knowledge, and attitude, existed regarding those errors. Garber showed that about half of the biases involved system and cognitive biases. Cognitive errors were the sole reason for about 30% of the biases [44]. According to the current findings, 11 cognitive errors were more significant in physicians’ decision-making, consistent with those of Saposnik et al. [31]. The analysis of diagnostic errors’ causes, including those of this study, may depend largely on physicians’ proficiency and specialty. According to the literature, such errors are more likely than cognitive errors to cause problems in physicians with inadequate experience or knowledge. The current results are consistent with those of Webster et al. [21].

Conclusion

In medical students’ curricula, moral and clinical decision-making are marginalized by teaching professors; however, the teaching of humanities, psychology, and even literature is required, along with critical thinking and cognitive errors. Initiatives to improve clinical education and the need to use cognitive science findings in the clinical setting are currently driving forces behind genuine medical decision-making. Instead of information gaps in medicine, clinicians’ taught processes may be the primary source of issues with medical decision-making; cognitive and affective errors are notable contributors to thinking failures, and the rising diversity of options might help to alleviate the such issue. Additionally, instructions in decision-making and critical thinking should be included in medical, graduate, and undergraduate programs. The first step in learning cognitive methods that could increase patient safety is to understand cognitive errors. Several significant features of cognitive errors are as follows. A cognitive error exists among human beings and is more important in some professions, e.g. physicians and judges. Some cognitive error categories are significantly common among physicians, which can lead to medical errors and have serious human and financial consequences. To reduce medical errors and their huge loss of life and money, the causes of medical errors must be known, which cognitive errors are among the reasons, and by reducing cognitive errors, decision-making can be improved. Hence, physicians should avoid long working hours, reduce medical fatigue, practice medicine during normal day times, and avoid making decisions in insufficient-sleep circumstances. Moreover, physicians should receive training to accustom their minds to repetitive exercises making their intuition more scientific for quicker decision-making without cognitive error.

Limitations

This review had some limitations. Many, but not all, known biases were found in the electronic search strategy; hence, there is a chance that some studies were not recorded for inclusion. Presented here, aimed at gaining cognotive errors associated with physicians decision-making. As another limitation, this review only examined qualitative studies, not quantitative studies, and solely considered English articles in the past 22 years.

Future direction

Contextual elements that affect the cognitive process have been stressed in some theoretical investigations, such as medical decision-making (MDM) competency. Hutchins contends that because cognition is ontologically bound by its environment, it cannot be studied in a vacuum. Therefore, future research should concentrate on the relationship between cognitive components and contextual elements. To develop the MDM concept, some unanswered questions, such as the following, should be addressed: What is MDM? Under what circumstances should a good choice be arbitrated? Which steps are learned and which are natural in the process? Importantly, which components are not context-specific or idiosyncratic? The amount to which people can self-regulate and actively choose their thinking or metacognition, as well as circumstances in which various decision-making processes may be more advantageous, should be the subject of further study. The usefulness and influence of various educational interventions on teaching certain decision-making techniques, as well as how educational training itself can induce cognitive bias, should be the subject of future research and be addressed.

Disclaimer

This manuscript was not copied in any part and is not under consideration in any journal.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tehran, Faculty of Psychology and Education (Medical Ethic No: IR. UT. PSYEDU. REC.1401.032.).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors take full accountability for the integrity of all study aspects.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank and appreciate the precious professors Ezzati, Shojaei, Hatami and Salehi.

References

Medical decision-making is full of uncertainty. A substantial percentage of decision-making biases were credited to physicians’ cognitive functions [1]. Human errors in medicine can be reduced through advances in cognitive sciences [2]. As a result, extensive research has been carried out on the discipline of cognitive psychology to decrease clinicians’ decision-making errors. These are among the most significant patient safety issues and the subject of much worldwide research work [3, 4]. Diagnostic errors lead to fatalities in nearly one in every 1000 cases, resulting in an estimated 40000 to 120000 deaths per year in the USA [5, 6]. Estimates indicate that financial decrement caused by unnecessary testing, treatment, and fatalities due to diagnostic mistakes accounts for almost 30% of yearly national healthcare costs in the USA [7]. Investigations on medical errors and their causes have significantly improved over the last two decades with cognitive psychology [8]. The core component of the diagnosis is decision-making, and medical decision-making is susceptible to biases. The Sullivan Group [9] reported personal encounters with numerous instances of highly veteran doctors and experienced clinicians committing deep biases affecting the thinking process [10]. David Eddy commented that clinical decision-making was not a viable field of research in the 1970s [11]. However, some claim that the modifications are not very significant since then. In a study of directors of medical clerkships, more than half said they did not give courses in clinical decision-making and thought less than 5% of students had excellent decision-making skills [12]. In the last decade, the interest in understanding medical decisions in dynamic areas has significantly increased. Biases caused by defective thinking processes, rather than insufficient knowledge, are referred to as cognitive biases, and they can be brought on by heuristics, emotions, prejudices, and other cognitive foundations which are not reasonable [13, 25]. Therefore, students should be educated about various biases in clinical decision-making and various strategies used for cognitive bias mitigation [14].

In previous research, all cognitive errors have not been coherently addressed, and few studies have examined cognitive errors in physicians’ decisions. This article is an up-to-date, systematic meta-analyses review concentrated on the highly-repeated, significant errors in the reviewed articles 40 cognitive errors based on the repetition count disregarding their incidence and general prevalence rate.

This review study aimed at identifying the cognitive errors associated with physicians’ decisions with the following main research question: According to available qualitative research, what cognitive factors are associated with physicians’ decisions?

Materials and Method

The recommended reporting items for systematic review (PRISMA or Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) standards were followed in this qualitative systematic review study report [15], as well as the enhancement of reporting transparency for the synthesis of qualitative research findings [16, 17].

Data sources

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tehran, Faculty of Psychology and Education (Medical Ethic No: IR. UT. PSYEDU. REC.1401/ 032/). This review considered qualitative research studies containing the information, including each study’s data collection and analysis, both of which used qualitative approaches. PubMed and Medline were systematically searched for relevant posts on cognitive mistakes. Due to imposed sanctions on Iran, Embase articles were not accessible.

Study selection

Articles that met one or more of the following four inclusion criteria were considered candidates for the study: at least one outcomes measure was reported, the study was published in English, it involved doctors, and at least one cognitive element or an error was examined and predefined. The articles that met the requirements for inclusion were examined for any cognitive errors, methodological issues, and the expansion of the impact on therapeutic or diagnostic judgment. Non-qualitative studies and those with a statistical population of non-physicians were excluded. The study used the data that the authors had reported.

Search strategy

In studies published in English from 2000 to 2022, in the last two decades, the cognitive errors that physicians made in diagnosing and decision-making were investigated. The search included the following MeSH terms: “Cognitive bias” [or] “decision-making”, [or] “clinical decision-making”, [or] “medical decision-making”, [or] “physician” and “qualitative research” and a combination of them.

Selection process

Two authors independently screened the titles and read the title-relevant abstracts. Two researchers retrieved and reviewed the full papers for related abstracts, and they also checked the entire texts of possibly qualified publications for the inclusion criteria. Disagreements are resolved through discussion and consensus. Data extracted literatim from selected papers directly into the NVivo-11 program. Before including in the evaluation, the methodological quality of the papers was assessed by two independent reviewers utilizing the PRISMA instrumentation. Cohen’s kappa also applied to assess agreement, and the kappa score of at least 0.72 indicated good agreement among observers.

Data extraction

The study data were extracted according to the PRISMA statement (Figure 1). To ensure the necessary accuracy and correct extraction of content from the articles, two reviewers looked at the titles and abstracts. Utilizing standardized collecting appearances, data were extracted. Data were gathered based on the study country, design, publication year, the number of studied cognitive errors, type of results, and summary of essential findings.

Data analysis

The findings from qualitative investigations were first classified line by line while taking both content and meaning into consideration. Rereading and recoding were required during this procedure, as well as discussions among the research team to ascertain whether new codes were required or the current codes should be reevaluated. Through a deductive method, the analysis was theoretically motivated by the literature on cognitive reasoning models. The researchers also kept an eye out for any fresh ideas that might come from the data alone. As a result, the development of descriptive themes was based on the correspondence of concepts from one study to another, which allowed for the recognition of similar concepts between studies and the creation of a hierarchical coding structure based on similarities and differences between codes. According to Thomas and Harden, the third stage comprised an iterative study of the outcomes of the previous two stages [18].

Data items

As shown in Table 1, the following additional data were gathered for each included study: title, authors, publication year, country of origin, method, and journal title.

.jpg)

Results

Table 2 lists cognitive errors reported in 19 reviewed studies.

From the 19 analyzed studies, 40 cognitive errors were found: Aggregate, ambiguity aversion, yin-yang out, feedback sanction, visceral, anchoring, vertical line failure, ascertainment, unpacking principle, availability, sunk costs, base rate neglect, bias blind spot, conjunction rule, commission, confirmation, diagnosis momentum, explicit, framing effect, search satisfying, fundamental attribution, representativeness restraint, gambler’s fallacy, psych-out, gender error, hindsight, implicit, loss aversion, multiple alternatives, omission, optimism or optimistic, order effects, posterior probability, outcome, premature closure, overconfidence, zebra retreat, playing the odds, posterior probability, primacy or recently, and status quo. Table 3 presents a description of these cognitive errors.

Forty cognitive errors based on repetition count in the reviewed articles are shown in Figure 2. Discussion

Cognitive errors contribute significantly to medical mishaps. The evidence offered in this review suggests that attendance of error leads to errors in decision-making, and the outcomes of decisions are very concerning. Hence, the patient might be assessed, diagnosed, or given different treatments or services due to the presence or absence of information that should not have been included in the decision-making process. Therefore, cognitive, affective, or other errors can negatively affect the overall quality of medical decision-making. As shown in Figure 3, from 40 cognitive errors obtained from the 19 reviewed studies, 11 cognitive errors accounted for the largest repetition counts: availability (16 times), confirmation (15 times), overconfidence (13 times), anchoring (12 times), framing effect (10 times), omission (10 times), search satisficing (9 times), representativeness (9 times), premature closure (9 times), diagnosis momentum (9 times), and commission (9 times). The frequency of diagnostic bias is disappointingly numerous. Early detection of medical professionals’ cognitive errors is essential to improve clinical judgment and avoid clinical biases and imply more realistic patient expectations. This study determines the impact of doctors’ cognitive biases on clinical biases and medical tasks. Studies examining the anchoring effect, physician overconfidence, and information or availability inaccuracy may point to a connection with inaccurate diagnoses. Physicians’ enhanced coping strategies and ambiguity tolerance can be related to optimal management. Even while decision-making processes are similar across professions, mistakes would nonetheless play a substantial impact on decision outcomes in all healthcare contexts. The numbers reported for errors in this article, although relatively demonstrating the prevalence of cognitive errors occurring in physicians’ decisions, indicate such errors’ repetitions in the 19 reviewed articles, i.e., opinions of the authors were prioritized, as well as a deeper feeling, knowledge, and attitude, existed regarding those errors. Garber showed that about half of the biases involved system and cognitive biases. Cognitive errors were the sole reason for about 30% of the biases [44]. According to the current findings, 11 cognitive errors were more significant in physicians’ decision-making, consistent with those of Saposnik et al. [31]. The analysis of diagnostic errors’ causes, including those of this study, may depend largely on physicians’ proficiency and specialty. According to the literature, such errors are more likely than cognitive errors to cause problems in physicians with inadequate experience or knowledge. The current results are consistent with those of Webster et al. [21].

Conclusion

In medical students’ curricula, moral and clinical decision-making are marginalized by teaching professors; however, the teaching of humanities, psychology, and even literature is required, along with critical thinking and cognitive errors. Initiatives to improve clinical education and the need to use cognitive science findings in the clinical setting are currently driving forces behind genuine medical decision-making. Instead of information gaps in medicine, clinicians’ taught processes may be the primary source of issues with medical decision-making; cognitive and affective errors are notable contributors to thinking failures, and the rising diversity of options might help to alleviate the such issue. Additionally, instructions in decision-making and critical thinking should be included in medical, graduate, and undergraduate programs. The first step in learning cognitive methods that could increase patient safety is to understand cognitive errors. Several significant features of cognitive errors are as follows. A cognitive error exists among human beings and is more important in some professions, e.g. physicians and judges. Some cognitive error categories are significantly common among physicians, which can lead to medical errors and have serious human and financial consequences. To reduce medical errors and their huge loss of life and money, the causes of medical errors must be known, which cognitive errors are among the reasons, and by reducing cognitive errors, decision-making can be improved. Hence, physicians should avoid long working hours, reduce medical fatigue, practice medicine during normal day times, and avoid making decisions in insufficient-sleep circumstances. Moreover, physicians should receive training to accustom their minds to repetitive exercises making their intuition more scientific for quicker decision-making without cognitive error.

Limitations

This review had some limitations. Many, but not all, known biases were found in the electronic search strategy; hence, there is a chance that some studies were not recorded for inclusion. Presented here, aimed at gaining cognotive errors associated with physicians decision-making. As another limitation, this review only examined qualitative studies, not quantitative studies, and solely considered English articles in the past 22 years.

Future direction

Contextual elements that affect the cognitive process have been stressed in some theoretical investigations, such as medical decision-making (MDM) competency. Hutchins contends that because cognition is ontologically bound by its environment, it cannot be studied in a vacuum. Therefore, future research should concentrate on the relationship between cognitive components and contextual elements. To develop the MDM concept, some unanswered questions, such as the following, should be addressed: What is MDM? Under what circumstances should a good choice be arbitrated? Which steps are learned and which are natural in the process? Importantly, which components are not context-specific or idiosyncratic? The amount to which people can self-regulate and actively choose their thinking or metacognition, as well as circumstances in which various decision-making processes may be more advantageous, should be the subject of further study. The usefulness and influence of various educational interventions on teaching certain decision-making techniques, as well as how educational training itself can induce cognitive bias, should be the subject of future research and be addressed.

Disclaimer

This manuscript was not copied in any part and is not under consideration in any journal.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tehran, Faculty of Psychology and Education (Medical Ethic No: IR. UT. PSYEDU. REC.1401.032.).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors take full accountability for the integrity of all study aspects.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank and appreciate the precious professors Ezzati, Shojaei, Hatami and Salehi.

References

- Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165(13):1493-9. PMID]

- Zhang J, Patel VL, Johnson TR. Medical error: Is the solution medical or cognitive? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002; 9(6 Suppl):S75-7. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Graber M. Diagnostic errors in medicine: A case of neglect. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005; 31(2):106-13. [DOI:10.1016/S1553-7250(05)31015-4]

- Singh H, Graber ML. Improving diagnosis in health care-the next imperative for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(26):2493-5. [PMID]

- Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving diagnosis in health care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015. [PMID]

- Singh H, Meyer AN, Thomas EJ. The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: Estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014; 23(9):727-31. [Link]

- Singh H, Schiff GD, Graber ML, Onakpoya I, Thompson MJ. The global burden of diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017; ;26(6):484-94. [PMID]

- Coughlan JJ, Mullins CF, Kiernan TJ. Diagnosing, fast and slow.Postgrad Med J. 2021; 97(1144):103-9. [PMID]

- O'Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018; 48(3):225-32. [PMID]

- The Sullivan Group Quarterly. Avoiding cognitive bias in diagnosing sepsis. Brighton : The Sullivan Group Quarterly; 2017. [Link]

- Eddy DM. Evidence-based medicine: A unified approach.Health Aff (Millwood). 2005; 24(1):9-17. [PMID]

- Rencic J, Trowbridge RL Jr, Fagan M, Szauter K, Durning S. Clinical reasoning education at US medical schools: Results from a national survey of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med. 2017; 32(11):1242-6. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Stiegler MP, Tung A. Cognitive processes in anesthesiology decision making. Anesthesiology. 2014; 120(1):204-17. [PMID]

- Lambe KA, O'Reilly G, Kelly BD, Curristan S. Dual- process cognitive interventions to enhance diagnostic reasoning: A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016; 25(10):808-20. [PMID]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols [PRISMA-P] statement. Syst Rev. 2015; 4(1):1. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012; 12:181. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gülmezoglu M, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: An approach to assess confidence in finding from qualitative evidence syntheses [GRADE-CERQual]. PLoS Med. 2015; 12(10):e1001895. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008; 8:45. [PMID]

- Beldhuis IE, Marapin RS, Jiang YY, Simões de Souza NF, Georgiou A, Kaufmann T, et al. Cognitive biases, environmental, patient and personal factors associated with critical care decision making: A scoping review. J Crit Care. 2021; 64:144-53. [PMID]

- Fargen KM, Friedman WA. The science of medical decision making: Neurosurgery, errors, and personal cognitive strategies improving quality of care. World Neurosurg. 2014; 82(1-2):e21-9. [PMID]

- Webster CS, Taylor S, Weller JM. Cognitive biases in diagnosis and decision making during anesthesia and intensive care. BJA Educ. 2021; 21(11):420-5. [PMID]

- Klocko DJ. Are cognitive biases influencing your clinical decision? Clin Rev. 2016; 32-9. [Link]

- Lighthall GK, Vazquez-Guillamet C. Understanding decision making in critical care. Clin Med Res. 2015; 13(3-4):156-68. [PMID]

- Croskerry P. Achieving quality in clinical decision making: Cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Acad Emerg Med. 2002; 9(11):1184-204. [PMID]

- Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003; 78(8):775-80. [PMID]

- Blumenthal-Barby JS, Krieger H. Cognitive biases and heuristics in medical decision making: A critical review using a systematic search strategy. Med Decis Making. 2015; 35(4):539-57. [PMID]

- Featherston R, Downie LE, Vogel AP, Galvin KL. Decision making biases in the allied health professions: A systematic scopin review. Plos One. 2020; 15(10):e0240716. [PMID]

- Bornstein BH, Emler AC. Rationality in medical decision making: a review of the literature on doctors’ decision making biases. J Eval Clin Pract. 2001; 7(2):97-107. [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00284.x]

- O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. A cognitive forcing tool to mitigate cognitive bias-a randomized control trial. BMC Med Educ. 2019; 19(1):1-8. [Link]

- Berner ES, Graber ML. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med. 2008; 121(5 Suppl):S2-23. [PMID]

- Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, Tobler PN. Cognitive biases associated with medical decision: A systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016; 16(1):138. [PMID]

- Watari T, Tokuda Y, Amano Y, Onigata K, Kanda H. Cognitive bias and diagnostic errors among physicians in Japan: A Self-Reflection Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4645. [PMID]

- Stiegler MP, Neelankavil JP, Canales C, Dhillon A. Cognitive errors detected in anesthesiology: A literature review and pilot study. Br J Anaesth. 2012; 108(2):229-35. [PMID]

- Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care diaparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013; 28(11):1504-10. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Elstein AS, Schwartz A. Clinical problem solving and diagnostic decision making: Selective review of the cognitive literature. BMJ. 2002; 324(7339):729-32. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Croskerry P. The cognitive imperative: Thinking about how we think. Acad Emerg Med. 2000; 7(11):1223-31. [PMID]

- Greenhalgh T. Narrative based medicine: narrative based medicine in an evidence based world. BMJ. 1999; 318(7179):323-5. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.318.7179.323] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Elstein AS. Heuristics and biases: Selected errors in clinical reasoning. Acad Med. 1999; 74(7):791-4. [PMID]

- Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007; 22(9):1231-8. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gupta M, Schriger DL, Tabas JA. The presence of outcome bias in emergency physician retrospective judgments of the quality of care. Ann Emerg Med. 2011; 57(4):323-8.e9. [PMID]

- Saposnik G, Cote R, Mamdani M, Raptis S, Thorpe KE, Fang J, et al. JURaSSiC: Accurancy of clinician vs risk score prediction of ischemic stroke outcomes. Neurology. 2013; 81(5):448-55. [PMID]

- Simon, HA. Rational choice and the structure of the environmental. Psychol Rev. 1956; 63(2):129-38. [PMID]

- Heller RF, Saltzstein HD, Caspe WB. Heuristics in medical and non-medical decision-making. Q J Exp Psychol A. 1992; 44(2):211-35. [PMID]

- Graber Mark L. Diagnostic errors in medicine. A case of neglect. J Qual Patient Saf. 2005; 31(2):106-13. [DOI:10.1016/S1553-7250(05)31015-4]

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

medical education

Received: 2022/07/30 | Accepted: 2022/11/1 | Published: 2022/10/1

Received: 2022/07/30 | Accepted: 2022/11/1 | Published: 2022/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.jpg)

.jpg)